|

Squirrel, O squirrel in the attic, squirrel in the hole, squirrel my first spoken word of English – I love you, and my dogs love you, even though our ways of communicating this can be quite different. Squirrel – you are a visit from the wild, a telephone pole acrobat, a daredevil provocateur. Squirrel-of-the-north, little red squirrel scolding head-down, eye-level to me from the hemlock, whose rough bark you clutch in your clever little paws. Squirrel who gathers and shreds.

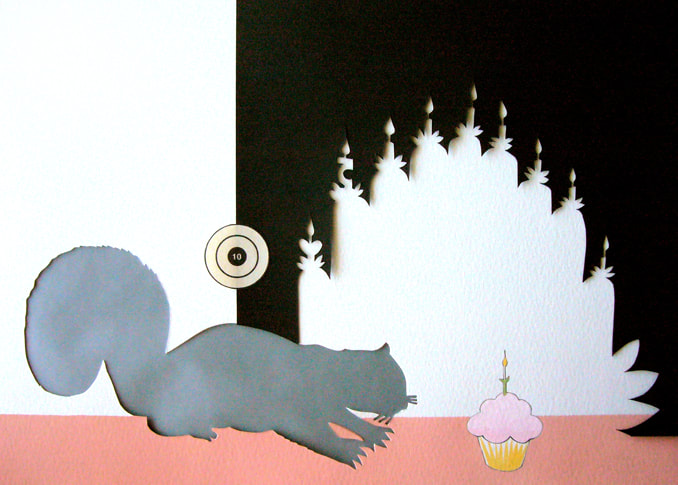

When I lived in Tennessee, I gathered buckeye nuts like some mad biped squirrel, filling pockets with glossy nuts, incredibly appealing, until they dried, and shriveled up. Carried through the winter, they became reminders of this part of Fall, where everything is golden: all the stored heat of summer cascading down in golden leaves, all the sunlight spending itself before night takes over. Right here, under this picnic table, someone has been squirreling smooth stones, a cache, to remember rough edges’ resolution into gentleness. Or, to chuck at peoples heads. I can’t presume. One day I looked out from the porch of the little yellow farmhouse I lived in, and I saw a tall, slightly stooped man circling the almost-ruins of the big buckeye across the street. He told me it was his way to drive here to Sewanee from – where? – Knoxville? – far! – each year, to find a buckeye for his pocket. Elegant, nostalgic squirrel. The next year, the tree finally and irrevocably died, and I never saw the buckeye pilgrim again. The thing about squirrels is: they’re kinetic geniuses. If they weren’t, my daily walks with two massive predators would be a lot less ethically sustainable, and the words would be littered with squirrel-corpses. They’re easy to find – the guard squirrel shrieks a warning to all – who dive or climb for cover – but they’re so fast and so confident that the matter how many times the dogs shove their heads up to the ears into burrows, or how high they strain their front claws up some trunk, there’s never any squirrel-slaughter to be had. Two creatures I have known who were actually capable of catching squirrels: my icehouse roommate Cooper’s sour black-and-white tom, and a farm apprentice in the mountains of North Carolina. The cat, I never saw an action, but there was a summer where every other day or so, he would leave a fresh tail for us on the porch. Only in retrospect did I realize I should have been saving them for the edges of some savage cloak. But by then they were gone to ants, and to whomever else settles carrion scores in hot Atlanta scrub. The farmhand was one of my friend Joe’s helpers – part-time tending to permaculture crops and mountain medicinal herbs, part-time doing his own thing, which in this case meant building a bow and arrows, and then stalking squirrels in the forests at the foot of Mount Mitchell. When he killed one, he would eat it, then stretch and tan the hide using the animal’s brains. He said his plan was to make a loincloth, so that when the squirrels saw him coming, they would be laughing so hard it would be easier to shoot them. “Old Fuzzy Nuts,” they’ll call me, he said, and it was impossible not to love him. Impossible not to love a squirrel: sine-waving through the grass, its tail a perpetual counterbalance and flourish. How is it we humans have been de-tailed? What a tragedy, what a root of loneliness and unworthiness! With a tail, you are always with someone to wrap around yourself, to swagger, to wrap around other someones, when you dance. Chloe and Elliot use theirs differently: hers is for stiffening in battle, for asserting her will in the world. His is for pythoning around those he loves, for thumping and circling when his joy is uncontainable. Imagine! If we had tails we wouldn't need phrases like, Oh thank you, how kind! or, May I have this dance? Our tails would express all this, and would comfort us at days’ end, built-in safety blankets and teddy bears. I wonder, if Donald Trump had a squirrel’s tail, would he calm the fuck down? Squirrels are not particularly calm, I will admit, but there’s a sane, embodied competence about them that we humans could learn a lot from. What if all the things we give so many names to – addiction, obesity, depression, anxiety, political strife – are just so many faces of the same basic wound up not liking or understanding our bodies enough to actually take up residence inside of them? The tai chi master who came to visit last weekend mentioned casually that Chinese medicine holds our human decision to stand erect as the root of many of our health problems. Instead of hanging down peacefully from below our spines, our guts get all mashed up together in the bottom of our trunks, and suffer. Plus, no tails for remembering and expressing the body’s joy, aggression, and love. Poor things! No wonder we are so confused. No wonder we can be fooled into thinking Twitter is ever a good idea. This same tai chi master taught us two new ways of walking: like a crane, and like a bear. The first – inhale, wrists float up – exhale, elbows float down – is good for bone-strength. The second is good for those mashed-up organs. Each arm snakes around, up and across, then climbs the back, alternating in a kind of burlesque wave that is satisfying as much for its – true enough – wriggling of one’s insides – as it is for its mad-sexy willingness to be present, right here, in this body, as it is. Bear-walk burlesque is my current favorite discovery at the intersections of dance, fighting, and movement. What would squirrel-walking be? I imagine a fluid hop, followed by a hovering look around. Squirrel’s graceful, and also alert. Throw in some nose-twitches and a chatter to all your fellow-squirrels. Squirrel-walk sees & doesn’t see the car-predator, the truck-predator, all the sad fluttering tails and blacktop-smeared bodies. Forgive us, Squirrel, for we know not what we do. |

AuthorJulie Püttgen is an artist, expressive arts therapist, and meditation teacher. Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed