|

The Karma Gadri, one of the main schools of Tibetan painting, comes out of a nomadic religious tradition that mostly did not build fixed monasteries. Instead, the Karmapa monastics and their entourage roamed the high plateau, stopping sometimes to put up their yak-hair tents, establishing temporary teaching encampments that had many of the features of big monasteries, but lacked their solid walls and placement in perpetuity. Chögyam Trungpa Rimpoche talks about what this must have been like from the villagers’ perspective. You go to sleep in your bed with your family and your animals all around you. In the night you hear maybe some bells, some hooves and mallet thumps, and when you wake up there is a whole new town in the pasture-land, grouped around a black tent-temple whose red banners snap in the wind. Inside, there is a library of books like bread-loaves wrapped in silk, surrounded by hanging paintings that spell out many-limbed permutations of wisdom and compassion. There’s a shrine with gleaming water-bowls and smoky butter-lamps lighting a golden Buddha that’s very large for easy transport over Himalayan passes. You’re shy of the new people: they seem tall, bald, and fierce, but then someone gives you a bowl of soup. You start sharing stories about the paths that lead to here & now, and a clear connection opens.

I’ve been trying the experiment of living on Karma Gadri terms. For this to work, it helps to leave open the question of who is the village and who is the roaming monastery. Either way, there is a temporary encounter with the potential for some kind of teaching to occur, and there is the importance of food as a connector of people. Food is a primary connector of people. One mobile pantry day, hundreds of families traveled overnight for their share of the Food Bank’s 17,000 pounds of food, forming a dawn encampment in the parking lot of the School of Theology. An entire tractor-trailer of donated food had also appeared, and so the Sewanee residents who turned up to help were given a completely temporary, very urgent and beautiful scenario to step into. We were not really the hosts, only the matchmakers between the people and the food. As the lone vegetarian among the volunteers, I somehow wound up distributing entire palette-loads of meat. “Would you like some ribs, ma’am? Maybe a little sausage?” It was the best job ever. People really wanted the meat, and while some part of my mind was thinking, “Really? More cholesterol?” I could also tell that the exchange that was taking place was absolutely essential, and that the role I was stepping into that day was pretty much Many-Armed Bestower of Porky Blessings. The animals were already dead; the people were already alive, and bringing them together at the altar of this folding table was an action imbued with inevitable sense. I turned up for another pantry day, to discover a gentle encampment of carrot, donut, granola, cubed chicken, fresh tomato, and macaroni tables, and relatively few people arriving to step into the role of food-recipients. A woman told me she was leaving a job she loved, because her husband had not had clean socks or underwear for six months (had he lost the use of his thumbs?) A student told me about living on an island off the coast of British Columbia, doing whale research and wearing ski pants to keep off the misty chill. We broke down boxes, moved tables into the shade, told summer-stories amongst ourselves, and waited. My turn to carry groceries came in the form of Sheryl, who quickly established several things: she is raising a whole bunch of grandchildren; she knows how to cook and preserve all kinds of food; and she is a talker who weaves her stories on a master-teller’s jacquard loom. Some people spin a single faltering thread. Some people shuttle back and forth between the present and one other line. And Sheryl is someone who has six colors flying back and forth to form her shifting stories, with needles carrying the extra patterns she sews over the surface of her cloth. The VA and how mean they are. The one-room schoolhouse in Jump Off when she was a girl, and the teacher who came an hour before everyone else to cook cornbread lunch for the children. How the children used to come jumping across streams to get to school, and how her mother would substitute in the winter when the teacher couldn’t get there. The Franklin County police and how they like to use their radios to seem big. Her sons and how the military messed them up. How to preserve corn in a simple water bath. How to make cobbler out of canned peaches. How her daughter’s made sure that when her mother dies, she’ll get her fruit jars. How she’s seen trauma, and can deal with it, but she thinks being a teacher would be the hardest job in the world, because you never can tell what other people’s children have been through. I carry the first box of food. We fill it and come back for more. We each carry one more box to Sheryl’s truck, and then it’s really story-time. Sheryl’s grandmother put her in charge of making sure her older sisters didn’t get pregnant, and since Sheryl believed kissing could do the trick, this required a lot of vigilance. Her sisters’ threats to kill her didn’t seem to stop young Sheryl from breaking up their chicken-coop dates, so they saved money in a jar until they could pay someone to take on the role of Sheryl’s boyfriend and keep her distracted. But she had no interest. “I wanted to out-shoot, out-run, and out-wrestle the boys,” she says, “but I didn’t want a boyfriend.” They went to a drive-in movie and all she wanted to do was see the movie; they went to park & neck at Green’s View, and all she wanted was to see the valley in the moonlight. She started walking home alone in the middle of the night to escape the date, and then her sisters wanted to kill her even more. Now a car pulls up behind us and it’s Sheryl’s sister Belle. “Someone got pregnant on my watch anyway, didn’t she?” asks Sheryl, by way of greeting. Belle laughs, and we all start walking back up to the food tables. As we part, Sheryl says, “I’ll give you my phone number. Then if you like I’ll teach you, and we can do some canning, standing in the yard like two witches stirring our pots.” The opportunity for teaching. The truth that helping always goes both ways. The women stirring their pots, with the yak-hair tents behind them and the mountains under their feet. Two lives meeting and sharing the truths that arise when the heart opens wide as the clear blue sky. [Adapted from a series of stories I recorded in 2011, reflecting on my final four months of living and teaching in Sewanee, TN. Recordings are online at: http://www.turtlenosedsnake.com/storysmuggler.htm] I ask my nephew whether chicken in Switzerland tastes the same as chicken back home. He says chicken here tastes like fish, in a good way, and chicken at home tastes a little bit sour in the end. So I ask, it's better here, then? And he says, no, it's good both places. My nephew refuses to be pinned down on the subject of chicken. Which is pretty much a wise way to go. A while ago, in response to a friend's Planned Parenthood post, I opined that compared with the tragedies of unwanted & unsupported motherhood, abortion is a blessing. Another friend responded, it doesn't have to be not-tragic to be a blessing. Word. It's not because the Jesus story has come to encompass many layers of myth that Jesus wasn't also a real person. It's not because I'm right that you're wrong. Chickens taste good to my nephew in Baltimore as well as in Lausanne, and even if I don't eat chicken myself, I can still cut up his meat & point to each piece as it calls to him to be eaten. Chickens are fecundity are fearfulness are the mark that separates town from country, until someone in town decides she wants hens, and the whole Civil War-era compact Sewanee, Tennessee has been built on has to be re-examined. If we take to keeping chickens, does the town's proud separation from hillbillyhood dissolve? Do we revert? And if so, how long does it take, and what does it look like? As it happens, my friend and her chickens are altogether so charismatic that they are allowed to stay. Antoinette with her dowager's wig of white feathers, and her sisters of the green-speckled eggs, are granted amnesty, and Sewanee does not slide any steps further towards end-times uncivil ways. There are other Sewanee chickens - the cherished hens of the Green House, sheltered in a queenly coop & chicken tractor. My friend Sid and I are called in to bless them & so we do, chanting in Pali & sprinkling everything in sight with improvised holy-water from the springs in Shakerag Hollow. It's parents' weekend, whose dress code my friend has dubbed "rich casual," and yet I don't see a single Mom or Dad recoil when given a big fluffy talon-footed bird to hold. They take their offspring's feathery offspring - their grand-chickens - to their cashmered bosoms, proudly.

I am writing about chickens, and I am falling asleep right here at this table. I blame the cheese pie for lunch. I blame the amount of time it takes body & soul to re-find one another, after a journey 1/4 of the way around the world. Window open. Fresh air. Sleep chases away. We drop off Chloe at Good Dogma for boarding & training, and discover that chicken-distraction is part of the program. Paula, the dog savant who runs the place, has ordered a flock of hens and named the 13th "Spare." But, since Paula is a genius, no harm has come to any of the birds, even though so many dogs. Even though armed Libertarians doing target practice every time the Patriots play, Amen. I pull my shawl around me - open window means less sleepy, but also chilly. Chickens frying. Broilers, fryers, fancy poultry parts sold here. The ideas we prefer, about where our chicken comes from, as opposed to the things we know about CAFOs and horribly confined birds. Driving by the chicken-truck on the freeway - a dense concentrate of horror. What should be birds preening is sad infected piles collapsed on one another in wire stacks, never allowed the space or resources to develop into themselves. For this, for our malodorous and misguided mountains of food, we have a lot to answer. We chicken out of admitting the weight and the skid of our hungers. We cluck in sympathy. We allow ourselves to be blind to what we know, and we carry on as though our blindness were all that we are capable of. Chickenshit. But it's not true. Care. We are capable of care, and of admitting that we know what we know. This morning, I write to a friend who didn't get the job he really wanted. Knowing how good you would have been at it, and how much you cared about it, I am so sorry to hear this. There's more: Knowing how winding the path is, and how strange, I know that the next turn in the labyrinth will bring you to a place that resembles what you thought you wanted, only more closely, only less outside of yourself, and more naturally accessible. You will find it and it will find you. You have been seeking one another for millions of years.

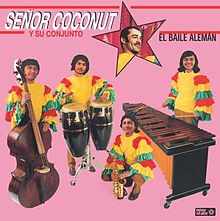

The labyrinth is a single path, emphasizing the turns rather than the straightaways. The maze is a mess of traps, but also only has one way through. I see these two are the same place, with different narrators. Do you feel the world is fundamentally out to get you? Welcome to the maze. Do you feel the world is fundamentally in cahoots with your own essential nature? Welcome to the labyrinth. The darkness. The sense of being stuck in the darkness, or of feeling your way through it. When I was 21, a family who'd lost a son in a mountaineering accident gave me a grant to go photograph a Shingon Buddhist pilgrimage in Japan. I had to park my crutches outside the Gothic hall where the interviews were held, in order to be convincing in my role as would-be walking pilgrim. In the end it didn't really matter, because mostly, I rode in the back seats of my fellow pilgrims' gleaming white Toyota sedans, dusty bottom sliding on the laminated lace covers they'd wrapped tightly over the upholstery. The deal was pretty paradoxical: start out with the intention of walking, and within twenty minutes, someone would screech to a halt, insisting politely that I join them for the day's temple round. Start out with the intention of hitchhiking - say, because I was lonely, or because my rain gear hadn't yet evaporated the previous day's monsoon - and I would walk for hours. So, Pavlovian-wise, I learned to set out with a steady walking pace, and accept the help that came to me if it chose to. Eventually, though, this bothered me. Come on! More sedans? This is no way to have an Adventure. So, walking on the side of a busy highway, I turned down a friendly offer. No, thank you. Today I am a walking pilgrim. Two hours later, when the same car stopped again, the charms of my resolution had worn off. Hideo, as it turned out, was ferrying his mother, a Shingon priest, to and from the hot springs. He was a devout pilgrim, and she was a straight-up über pilgrim, having walked the 88-temple circuit around the island on and off for more than sixty years, often in straw sandals. I would have been an idiot to turn this family down when they offered bed, rest, company, food, and friendship. For the next few days, Hideo drove me to the temples near the house he shared with his mother and sister. Because he actually knew where the temple were, and was intimately familiar with them, I could take a break from O tera wa doku desu ka? (where is the temple? one of my only reliable semi-Japanese phrases), and relax into seeing things more deeply. Shingon is "esoteric Buddhism," meaning that there are elements of the practice that are openly revealed, and others that are secret. Another way of saying this is that there are things you learn through experience that you can't know through ungrounded curiosity. Anyway, under one temple there was a labyrinth. The door of course was secret, and the space was meant to stay dark, even though it was painted all over with black-ground murals. Hideo asked me if I wanted to go down there, and of course I did. I remember holding his warm potter's hand. I remember my fingertips brushing the wall, counting the openings to pass, and the openings to enter into. I remember the sense of being in a space carefully engineered to evoke fear, and to channel it. To evoke love, and to assert its power in the dark. Now, I know this was probably a space for dark practice, as in, for voluntary retreat in the dark, allowing the mind to reveal itself without the familiar anchors of day and night, let alone white sedans and friendly old people. I did not know to ask Hideo or his mother: Have you practiced down there? What did you learn? Who taught you the turnings, and what was it like when you missed them? I grew up with The Tombs of Atuan, Ursula Le Guin's amazing story of the priestess Arha, and her slavery, and her dominion over the dark turnings of the Labyrinth under the Tombs. She sends prisoners to their deaths there, and she sends herself to the rescue of the light there. That book had its threads in the afternoon I spent much later, an Arha myself, envisioning hauling all the mummified remains of those I'd neglected to death, up to the light of day, out to dissolve into dust, and be released. The experience, sitting in that nunnery shrine room in Devon, was of clearing the labyrinth of my past debts. You, and you, and you, countless of you, I have allowed to die without nurture. I have starved to death without light or water. All of that is over now. You are clean. You are clear. I give your bones back to the light. I release you from this cycle, and in doing so, I release myself. Hideo didn't want to let me go, but he was a good man, and so he did. We drove to the pass just below the next temple, and he dropped me off in the parking lot. The temple keepers gave me access to their shower, and then I slept in the woods at the edge of their grounds. It was something I needed to do: to be a stranger, to be cold, to face the wet without someone's guest room. In the morning I set out to close the loop, to find the exit of this 88-temple wander. The ending was the beginning. Same place, three weeks later. Hello, temple priests with your spotless robes & appealingly smooth shaved heads! I made it! And here are the scribes' signatures, the mailman's belt, the trucker's hat, and the grumpy monk's bracelet to prove it. I don't think I'll ever go back to Shikoku in this lifetime, but the basic scenario of it: this broad circle around an island, this shared journey, this imperative to set out with an honest heart - all of these apply everywhere, always coming home. The fingertips brushing the unseen frescoes, deep under the altar we see at the surface. Here we are. The possibility of keeping the labyrinth clear, so that others may pass. The faith that leads us to know that what we think we lack is actually a window into what we are preparing to receive. All of these. All of these, and more. The swinging door swings both ways, allowing smooth passage out of the kitchen and into the Rotary Club's Mexican-themed fundraising party, and smooth passage back into the dish area, bearing trays of people's soppy-napkin bar dregs. White people do not tire of ethnically-themed parties, or at least in this Rotary Club, they have not. Plastic sombreros for everyone! And maracas. Let's not forget those. I realize that I am not per se bothered by cultural appropriation. Actually, I am not even sure how "cultural appropriation" is supposed to be different from culture as a whole. Culture IS appropriation. That's how we wind up with anyone speaking a language in common & also how we make new things. Noticing some traveler coming through town in a cool pair of pants, we borrow that design & execute it in a cloth we'd previously only used for aprons. We cobble together some beautiful new thing out of this-and-that, woven together on the loom of our attention. We're curious. We teach each other stuff. We ditch old, stale ideas in favor of new ones. and we spruce up the old dance with some new components. The door swings both ways: the forms of protest you use to tell me I am an asshole for appropriating your culture may well have originated in my culture - insofar as it makes any sense to say yours or mine at all. No, I am not per se bothered by cultural appropriation. In fact, I find it is often the heart and thrilling soul of the subversions that most delight me. Lil Kim either has her lovely brown skin painted, or squeezes herself into a Vuitton-logo leather bodysuit (accounts vary), and French matrons suddenly find themselves carrying impossibly expensive handbags that they might actually be a little bit afraid of. Laurie Anderson learns how to produce the white male bureaucracy's Voice of Authority, and suddenly every TSA announcement is hilarious. Divine raids the Revlon aisle, and suddenly makeup becomes an elective performance of extra-sensory enhancement. Cultural appropriation is how we take on existing forms of art, fashion, music, and language, toss them together in an anarchic, greedy trickster salad, and see what happens next. There's nothing to break, and if what comes out sings better, looks badasser, and makes people want to walk around with a little bit more high-stepping glee, all the better. But the door of cultural appropriation sometimes just swings to the bankruptcy of existing forms so unwilling to open themselves to real change that they will air-quote their way through anything to avoid the real risk involved in bringing forth something new. That's what happened at the Rotary Club party. Problem: We are bored. Solution: We shall envision entertaining brown people somewhere else, who are not-bored. Problem: Why are they not-bored? Solution: Because they have fancy hats and better music than we do. At this point, true curiosity could kick in. The members of the Rotary Club could decide to start making fancy hats for themselves. They could decide to have a Best Fucking Hat Ever contest, and see who could staple, glue, fold, sew, cast, or tame the most amazing piece of headgear ever devised by humans. They could challenge themselves to listen voraciously to hours of all kinds of music from "South of the Border," figure out what they liked, and piece together an informed & passionate playlist. They could make their own songs, combining the new rhythms they'd learned with things they liked from their own music. They could mate the Charleston & the foxtrot with the new music, and dance all night in their eye-popping hats. That whole hat/song/dance scenario is basically people being creative, curious & aware, while giving themselves permission to do the unheard-of and sometimes terribly awkward things their souls are guiding them to do. When Señor Coconut decided to produce merengue covers of Kraftwerk songs, I assume he did not pause to consider the sensibilities of super-sensitive German minimalists, and wonder whether they might be traumatized by the addition of ruffles & bongos to anthems like Autobahn. When Werewere Liking was grabbing the Odyssey by the short hairs, I don't think she spent a lot of time worrying about whether Western classicists would feel safe in the presence of her hybrid epic. Señor Coconut and Werewere Liking were too busy making things to worry about that bullshit.

Back at the swinging kitchen door, though, we have to admit that the scene unfolding in the ballroom is not one of joyful improvisation and bawdy, risky revelry. Instead, people are snarfing desexed tacos with cheese dip, and slamming back Bud Lights. They are half-assedly giggling at the plastic, made-in-China Party City sombreros perched on one another's unimaginative gringo heads. Problem: We are still bored. Problem: We are vaguely aware that this whole Mexican-themed party thing is retarded, but we don't have any idea what to do about it, except to place competitive bids on the mini-meat-smoker, and have more Bud Lights. It's important to acknowledge a few things here:

The Yale professor who sent the email to her students, saying that she thinks Halloween is actually an appropriate time for subversion and shape-shifting was not encouraging everyone to head for Party City, and stock up on all the geisha and gangster consumes they could find. She was saying, find out what you really want to be, and take the chance on being that. Not because it's what your SAE brothers are doing, and not because it's what you think will get you laid, but because it's the weird form you're inexorably drawn to incarnate for this one night. So you want to be a gangster geisha? That's messed up, but OK. Make it work. Take responsibility for what you are doing, and make it 100% specifically what you are feeling, not some lazy sombrero of a slur. Let the door swing towards something never yet seen in this world, and swing back out to a shape you wear with wonder and delight. I think of shoes as being fairly inanimate, and in the best case, controlled by my wishes. I want you on: you are on. I want you off: you are off. But then, the thing that I've been joking about for years actually happens. You know: the thing where, after some Upper Valley shoes-off buddhist-yoga kind of an event, you come out, and someone else has walked off with your black clogs, leaving some other Goldilocks-unfamiliar, ill-fitting pair in their wake. That thing.

I come out of tai chi class, and find a pair of wide, scuffed, potato-like shoes, also in size 42, lurking roughly where mine had been. I am aware of outrage and disbelief, as well as some obscure sense of shame. How could this person not have noticed that the shoes on their feet were Mine - broken in by my long feet, waterproofed by my fingers? What is it about me - permissive? vague? - that encourages people to walk off with my shoes? My friend suggests I wear my flimsy canvas tai chi slippers, leaving the mystery pair at the dojo, with a note. I wear ankle boots for the rest of the day. A message comes from a fellow-student, saying my clogs have gone to Burlington, and had an intense time with a friend of hers. She didn't notice the switch until bedtime. My shoes are back in the dojo. The shoes have traveled without me, giving me time to settle into basic plenitude. Nothing missing. Goldilocks' worries eased down and laid to rest. Someone else is wearing my tai chi slippers, even though my name is on the soles, with little hearts. That someone is standing next to me in class, and she's wearing my shoes because someone else took hers. Walk a mile in someone else's shoes takes on a whole new meaning when they are wondering where the fuck their shoes went. Once in the middle of the night, my friend Maguelonne and I borrow a pedal-boat off the beach in Sainte Maxime, and paddle across the bay to Saint Tropez. Maguelonne, whose hash-smoking is more thorough than my novice efforts, becomes convinced that there is a man swimming under the boat. I become convinced that freaking out is no way to navigate dark waters, and convince Maguelonne to start pedaling again. Flap-flap. Flap-flap. We orient to the Quai d'Honneur, the front row dock where people display their yachts for general awe-striking. Two seventeen-year-olds in a borrowed pedal-boat notch themselves neatly between the v-shaped hulls of two floating palaces. The palace crews throw down ropes, and we lash ourselves gamely to our hulking neighbors. Against all odds, we've made it across the dark sea & over the dark diver & against the current that some other night might have swept us off to Corsica. Victory! Time to dance. But our sandals linger in the sand on the other side of the bay, and without shoes, none of the boîtes de nuit want anything to do with us. No one wants to give us their shoes, so in the orange streetlight, we talk passersby into giving us their socks. But strangers' socks do not make these two weird lady pirates more attractive in the eyes of French bouncers. We two weary ones give up the struggle, and paddle home temperately in the soggy socks of our adventures. Oh, shoes! Oh, socks! Oh, dark harbor, night ocean! My shoes went to Burlington, my shoes went to my friend's bed, and the shoes I am wearing in their absence cannot in any true sense be said to be mine at all, having grown on the back and belly of some Australian sheep with plans of her own for that very skin. French for clog is sabot, same as a horse's hooves. What is the relationship between sabot and sabotage? Some terrible thing armies did to the feet of one another's horses. Some factory worker throwing her wooden shoes into the cogs, bringing the line to a shuddering halt. I wonder where my shoes went without me? is also I wonder if it's possible to stop settling for the ease of rapine? I bring three pairs of shoes in for repair: my husband's buffalo-boots, coming unglued; my winter boots, down at the heel; and my Krishna-skin boots, too tight at the instep. Together, these repairs easily add up to some cheap new pair, but I find I can't throw away leather anymore. I want to wear shoes till they can't be mended anymore with new bits or cannibalized components. I want to observe the whole span of a skin's life after its animal maker has been killed. Same for down. Where do the feathers go, once the birds are gone? I want to be aware of each night curled under birds' wings and breasts. I want to break the spell of the new. Where does our attention go, when it's not on our shoes? To nervous acquisition, and perfection. To endless email. To searching out the next pair of shoes, and to the dynamics that make Hanover the Zappos-buyingest town in the country. Give me new shoes, new stuff, but not new mud to walk upon. Feeling into the soles of the feet, I have no need for new anything. The shoes can go wherever they like, but the feet are right here, on the earth, grounded and inalienable, until this old skin too goes somewhere no one can describe. |

AuthorJulie Püttgen is an artist, expressive arts therapist, and meditation teacher. Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed