(M)otherbible Gallery

(M)otherbible Manifesto

(M)otherbible at the Flea Market

There was a blacksmith at the flea market in Fairlee, Vermont who sold beautifully honed and restored tools – antique double-headed axes, hatchets, pickaxes – all heavy, deadly-looking, and powerful. Secretly, I wanted an axe, but something instead pulled me towards a beat-up, nineteenth-century Gallery of Bible Stories laying on an old blanket in the stall next door. Story of my life. Its covers were falling off. It had wild Gustave Doré engravings and beautiful gilt edges. I haggled the seller down to twenty bucks and walked off with this strange prize under my arm, feeling vaguely haunted among people looking at trivets and buying jam on that bright July morning. Now what?

Wrapped in archival glassine, the Bible sat on my bookshelf for a decade. I wanted to do something with it, but I wasn’t sure what. Cannibalize it? Paint it? Collaborate with others to create a communally altered book? Nothing resonated enough for me to move forward wholeheartedly. Whatever I chose, I knew I wanted to commit to a single process and follow through with it for the entire artifact.

The COVID-19 pandemic hit around the same time I that was completing a yearlong practice of sewing monthly thangkas – Tibetan-inspired scroll-paintings – co-arising from found everyday fabrics and Buddhist texts chosen by members of the women’s Art/Dharma group I’d founded a year earlier. Now in self-isolation at home, and with a second year of Art/Dharma about to begin, I was ready for a new sacred/ordinary art assignment.

(M)otherbible is Born

I started looking more closely at the structure and content of my flea market Doré Bible. Its pages – as is often true for industrially-produced paper of that era – are brittle at the edges and spine. They are grouped into signatures (bundles) of four folios (two-page spreads) each. The original binding used metal staples – now rusty – to attach the signatures to a gluey spine. Its thick, embossed covers had torn away from the text block. Each illustration and its accompanying text are printed on one side of the sheet; the verso is blank. Between the pages, I found traces of dead insects and long-gone four-leaf clovers.

With my hands, I started to imagine a dual process: I would repair the book and rework it at the same time, using tools and materials that were already in my studio. A friend had given me Japanese tissue paper that I could use to reinforce the page-creases; another friend had brought me old cotton sheets that I could use to protect the pages as I ironed the creases and mildew out of them. I had a good supply of acid-free glue, wax paper, and cloth-covered brick weights. I also had piles of printed matter for collaging, foraged from the dump, the library discard pile, the recycling bin, and other not-quite-trash.

So I started the one-woman Pandemic Bible Study that became (M)otherbible. I decided to re-work two signatures each week. This meant creating that week’s collages (right-brain intuition), as well as mending the spine-creases of the following week’s signatures (left-brain sequential logic), so the tissue repairs would dry in time. Three days a week, I would go to my office in a mostly deserted building and see my therapy clients via Zoom. Four days a week, Bible Studies, remote 5Rhythms dance sessions, forest romps with my dogs, therapy, grocery store, supervision, repeat.

I have spent a lot of time in meditation retreat and studio production, so this improvised weekly rhythm felt quite natural to me. Yes, the heart of the pandemic carried devastating news; and, yes, I felt anchored by meaningful work.

I was and am quite fortunate in this.

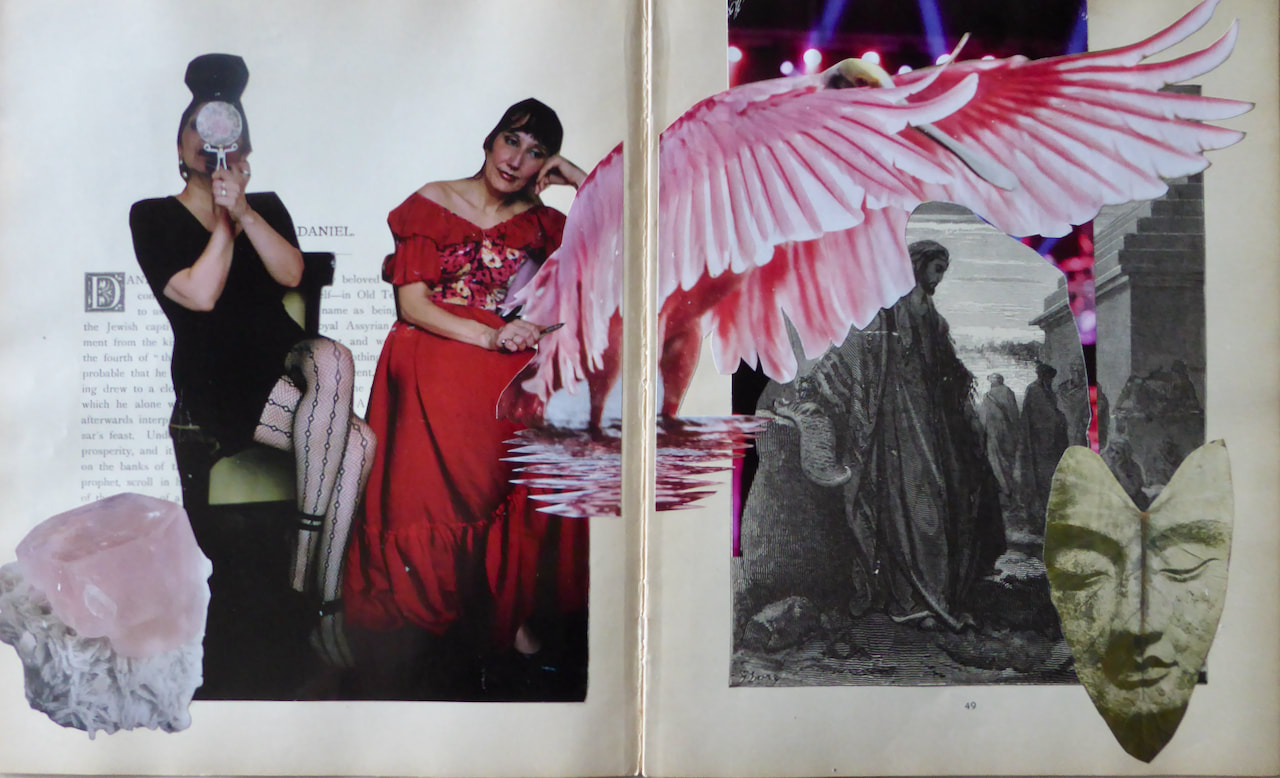

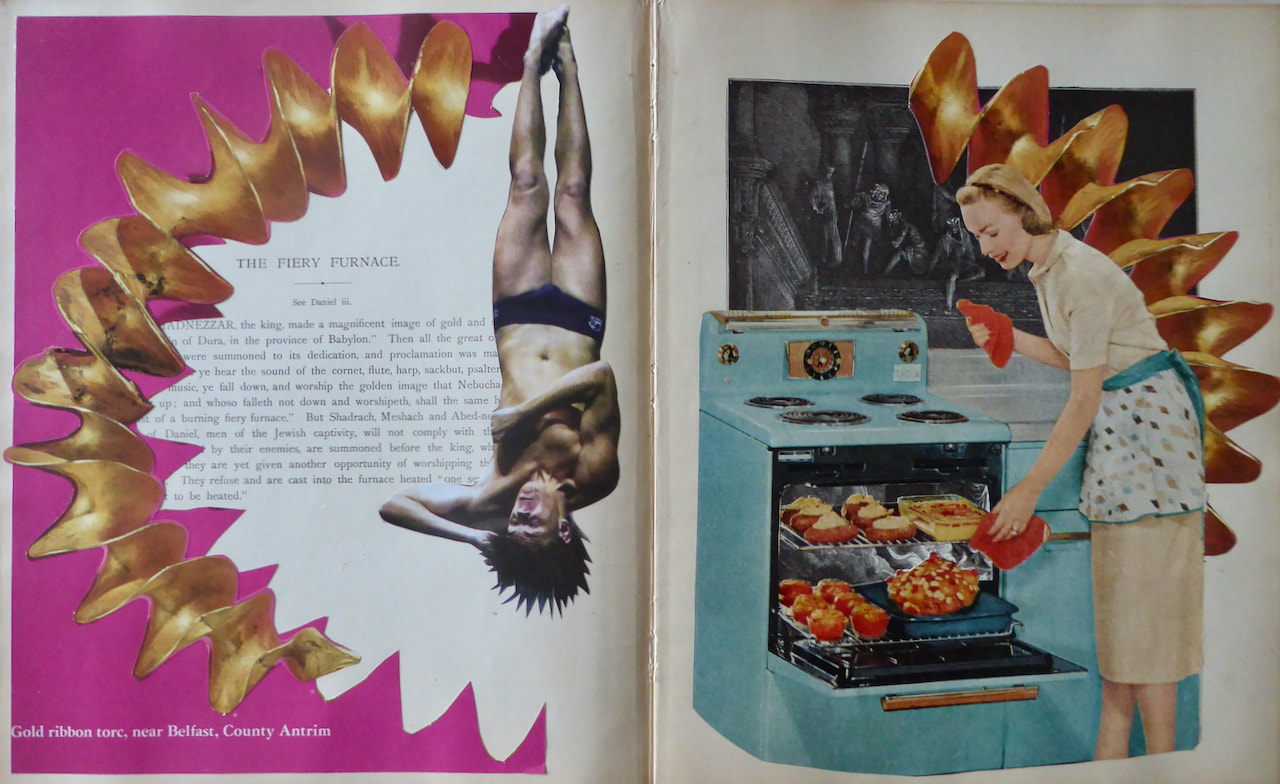

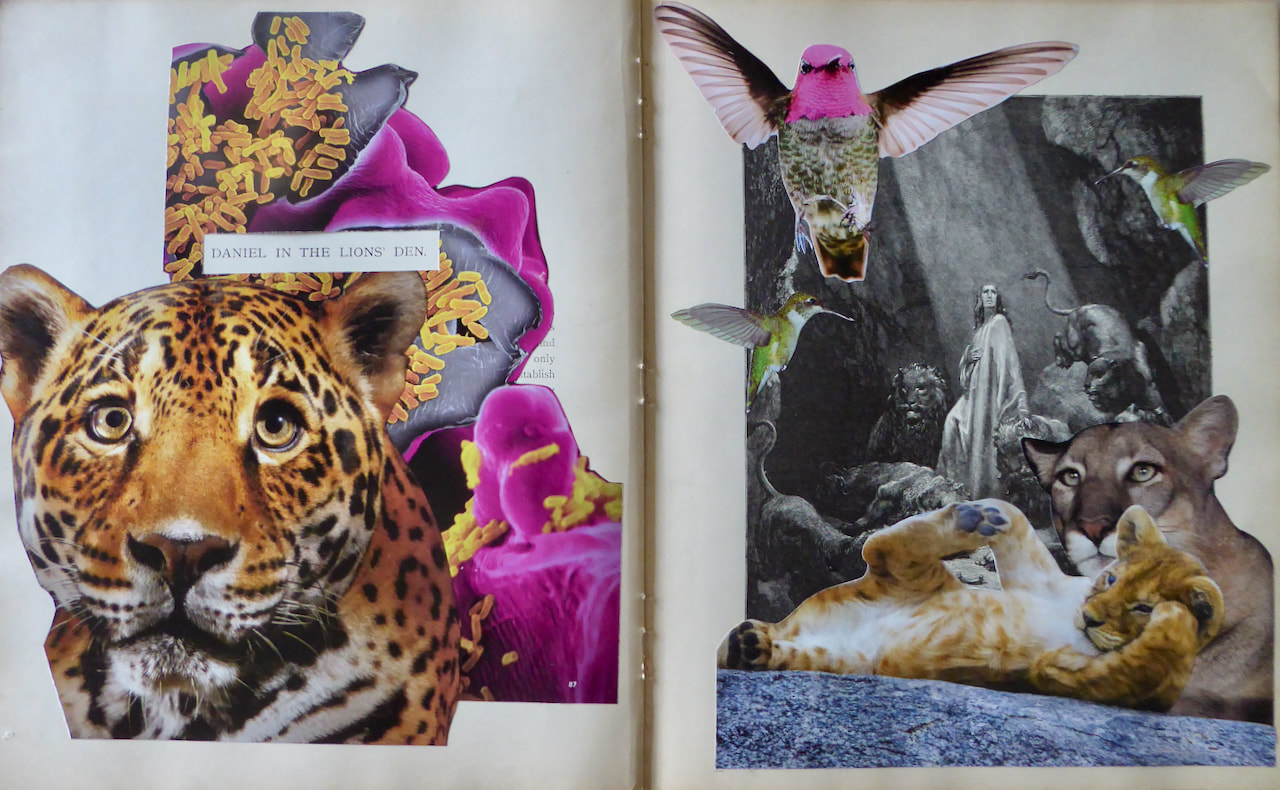

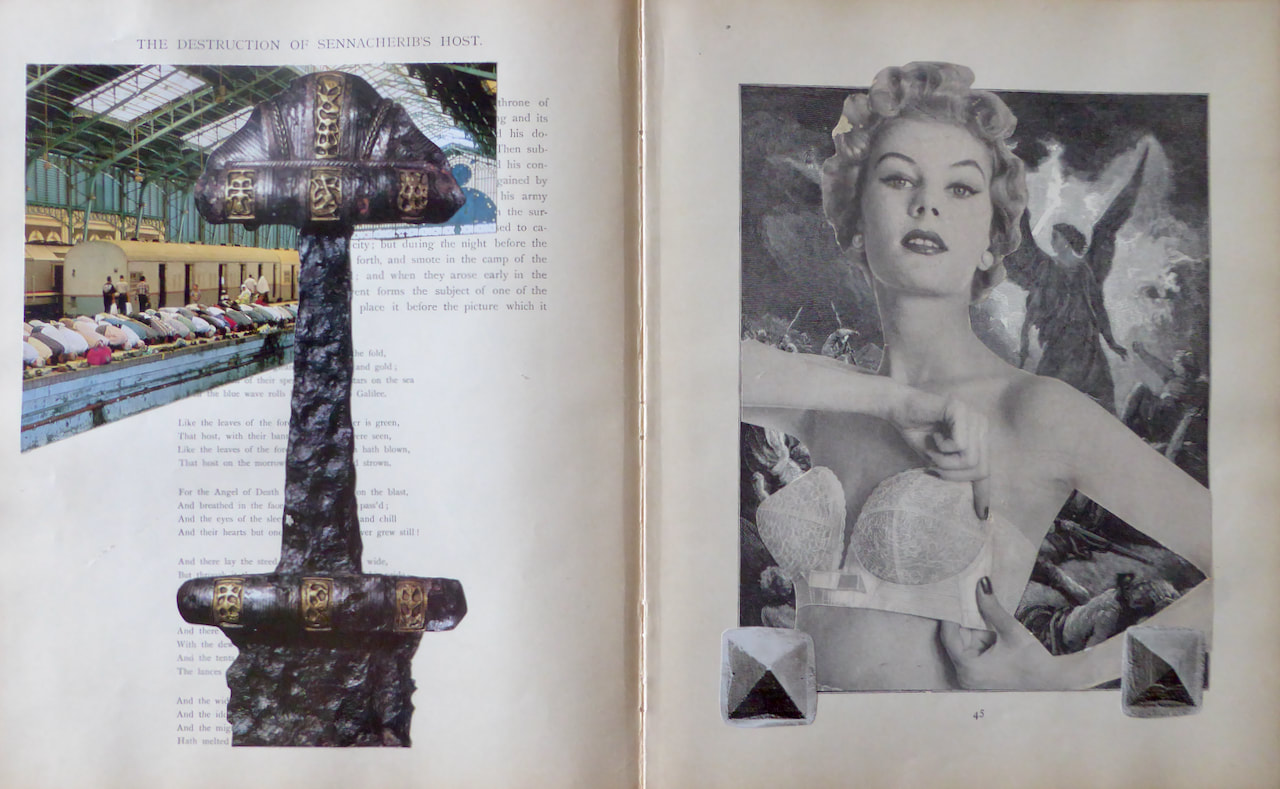

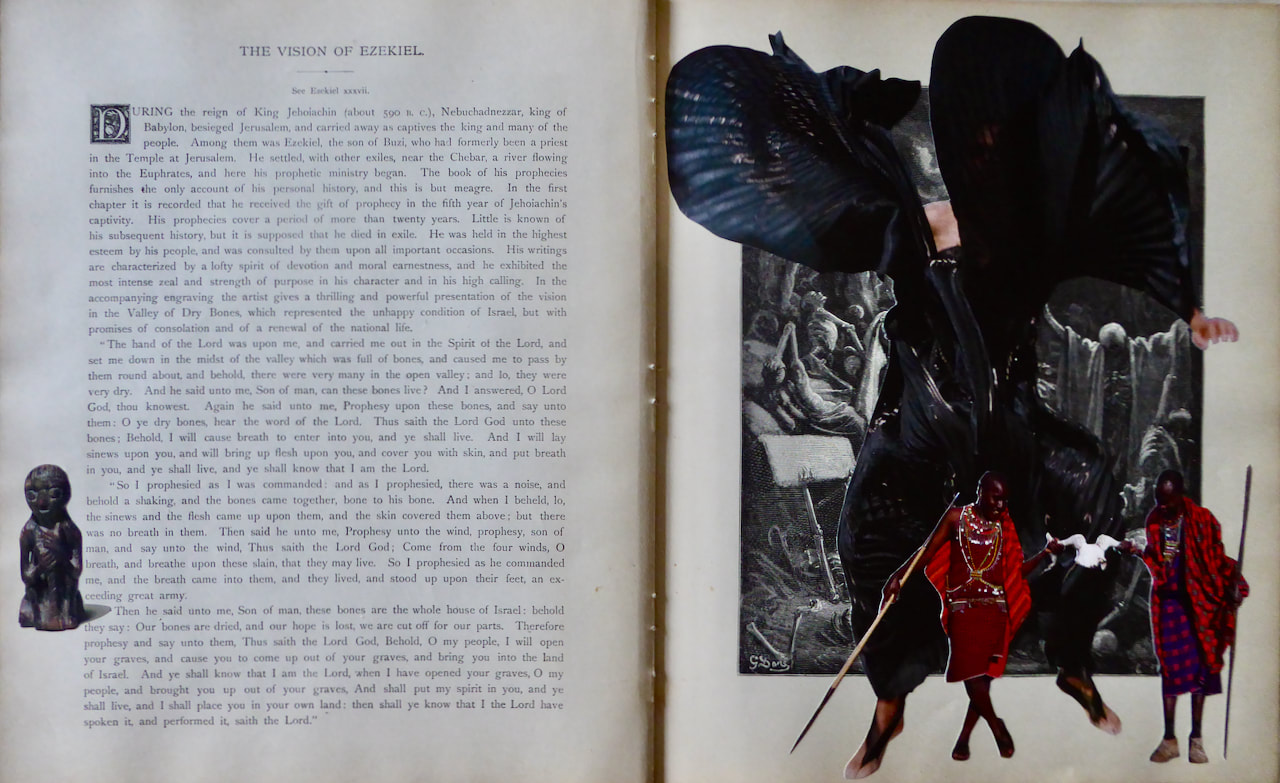

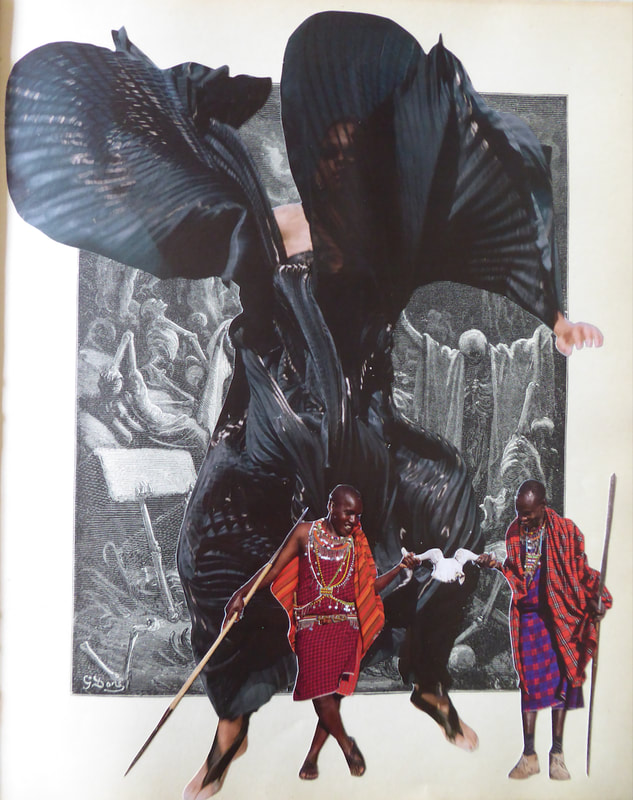

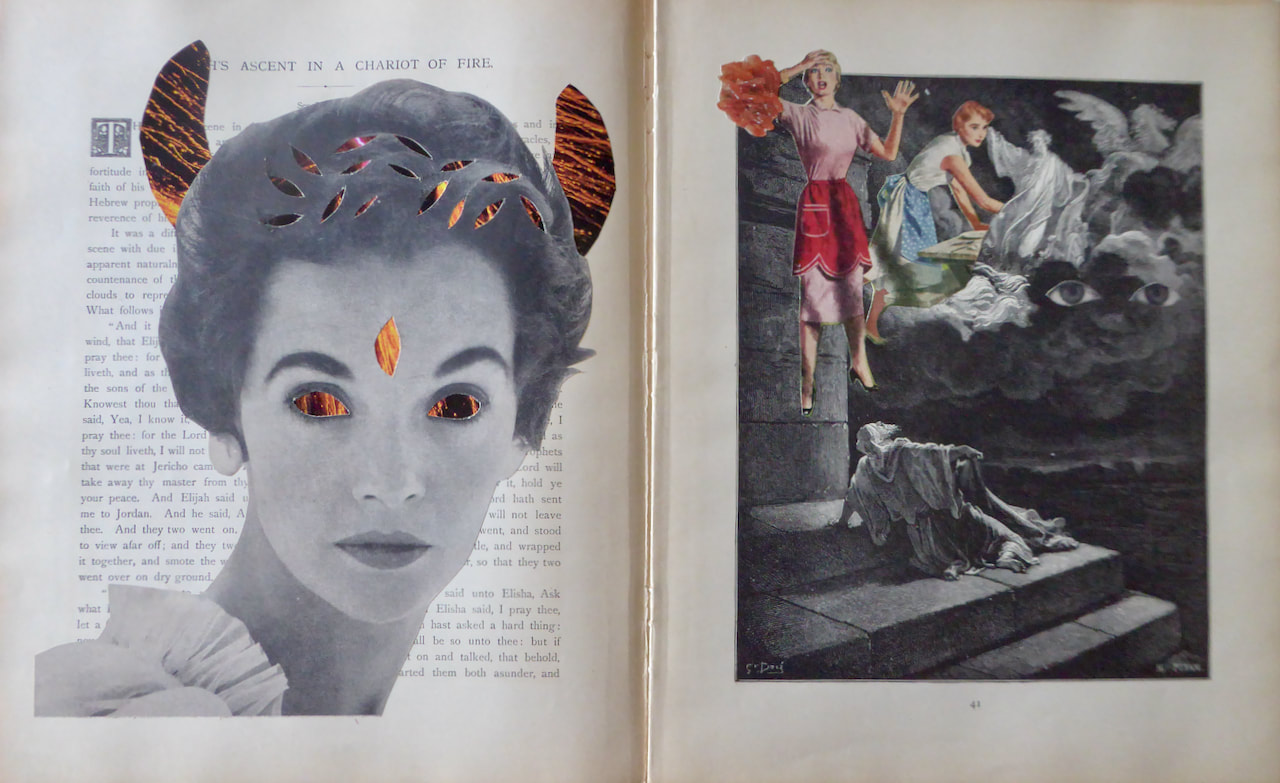

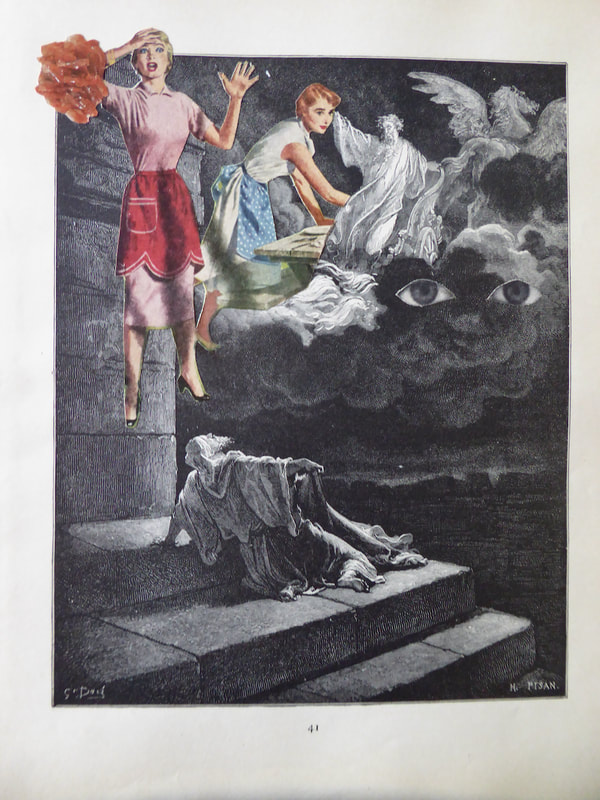

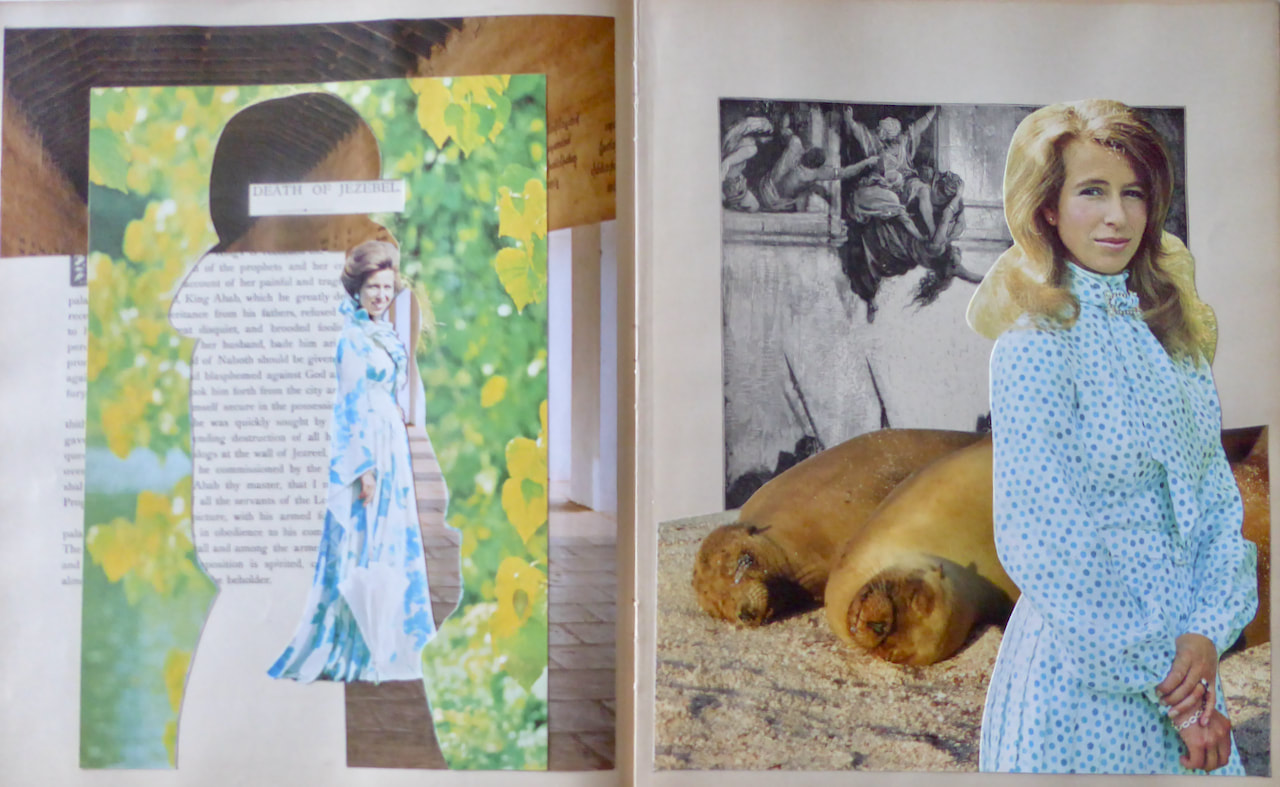

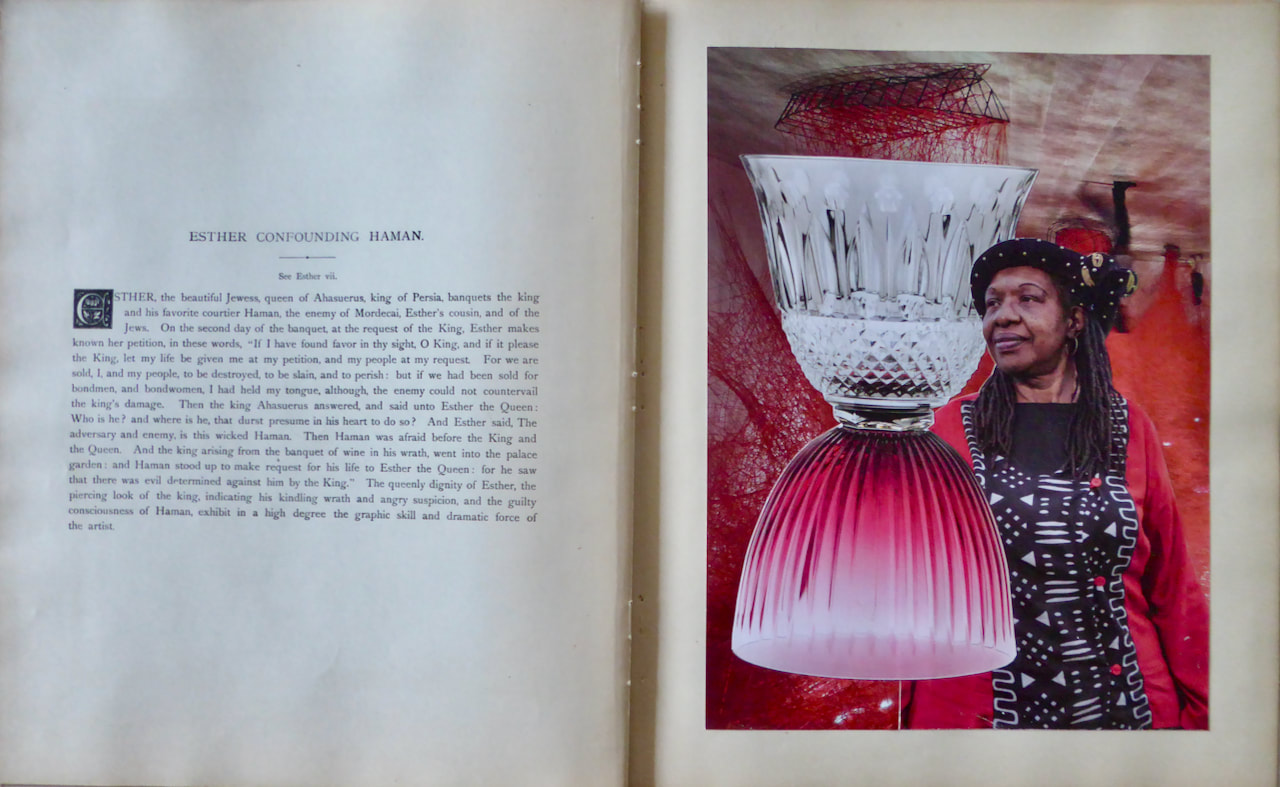

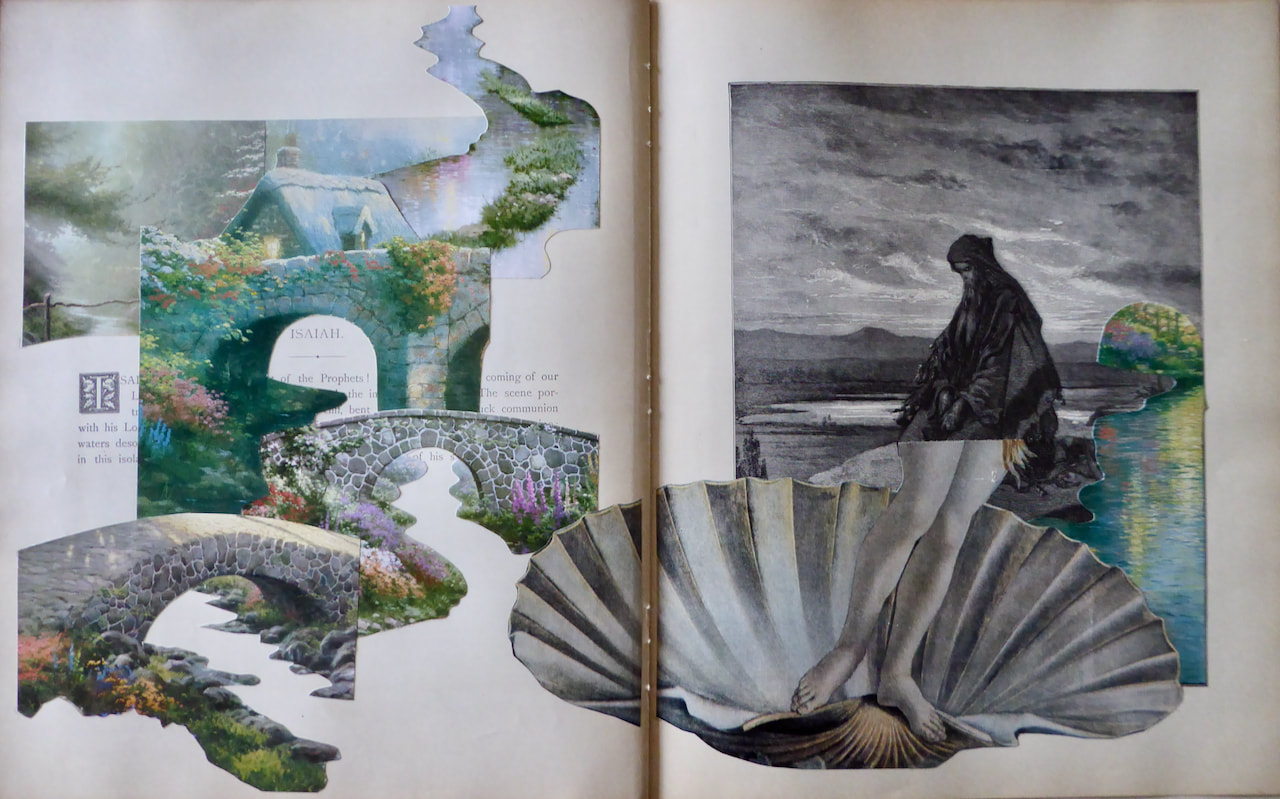

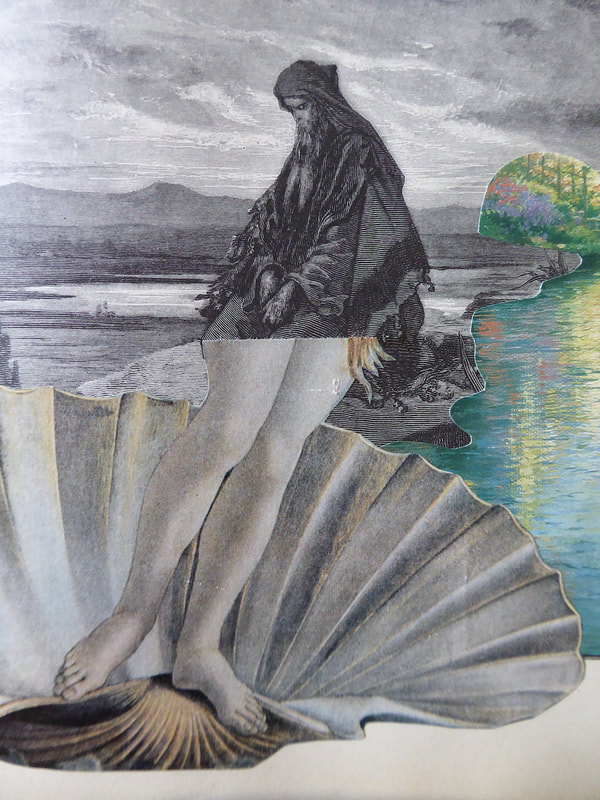

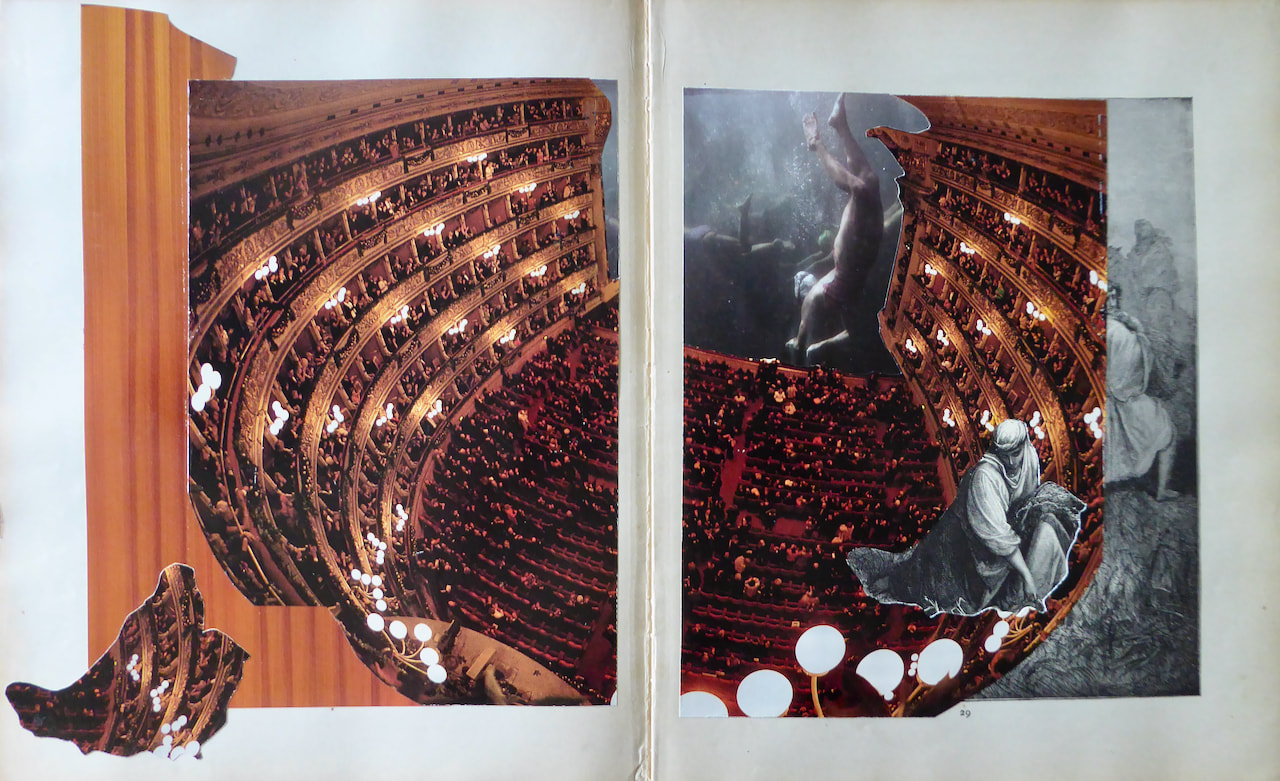

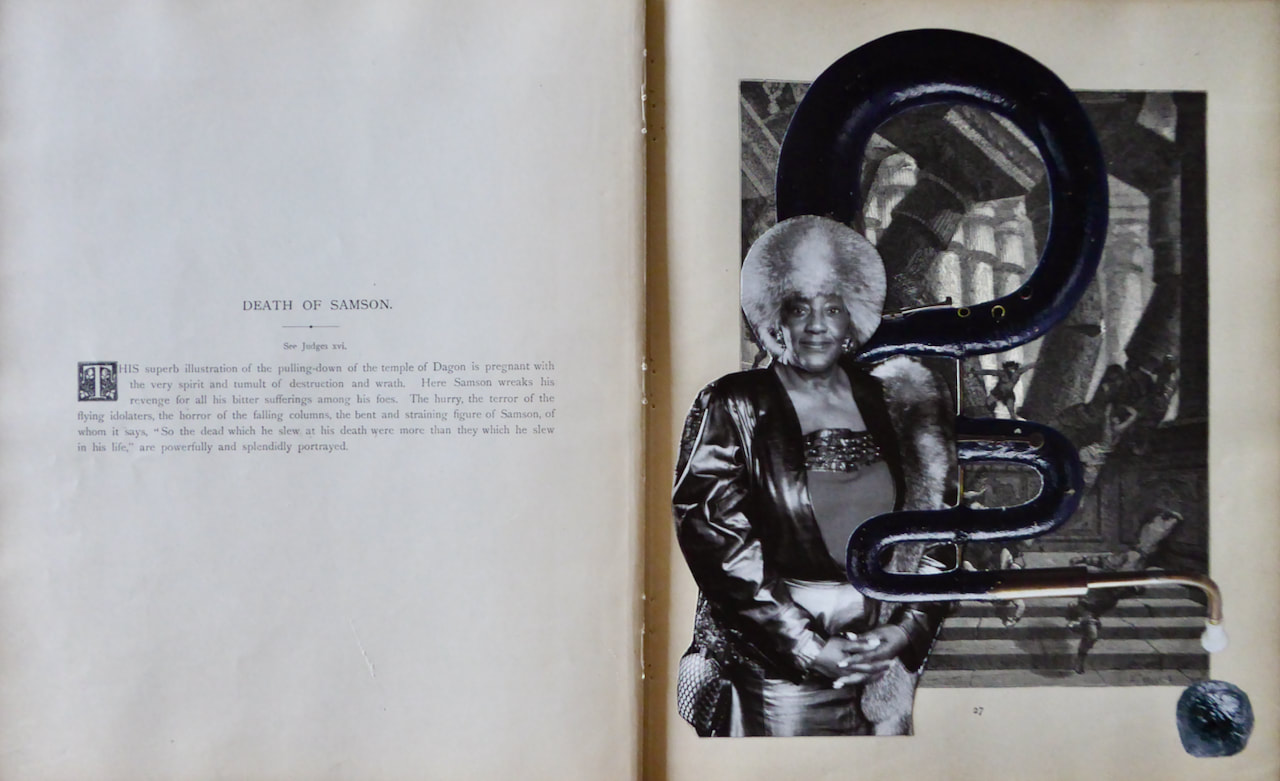

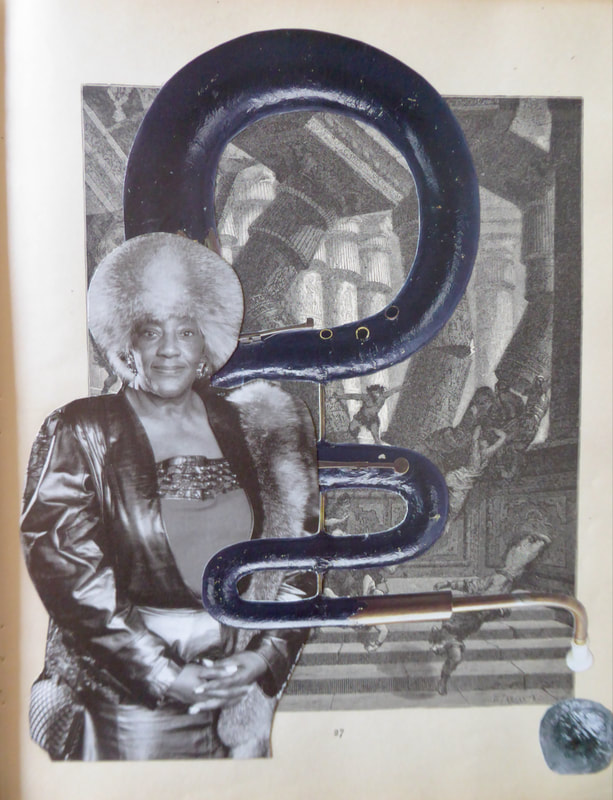

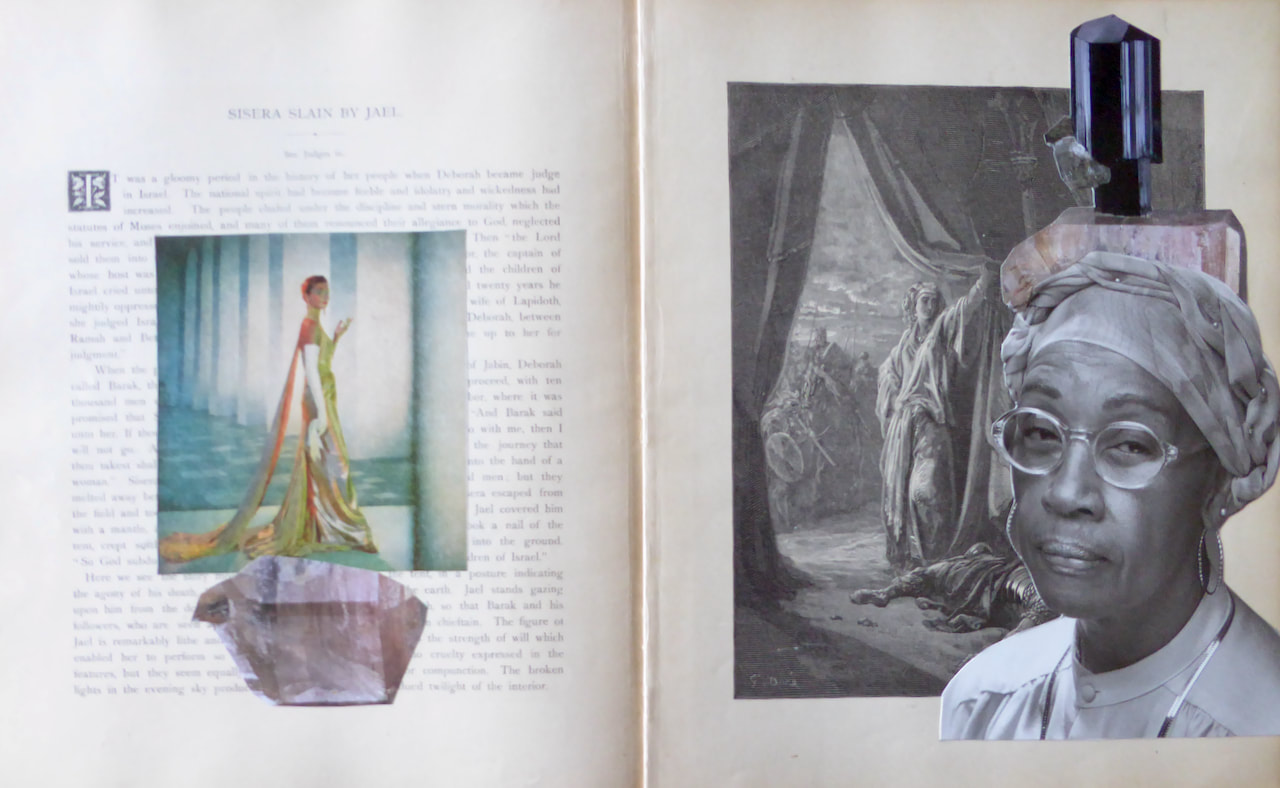

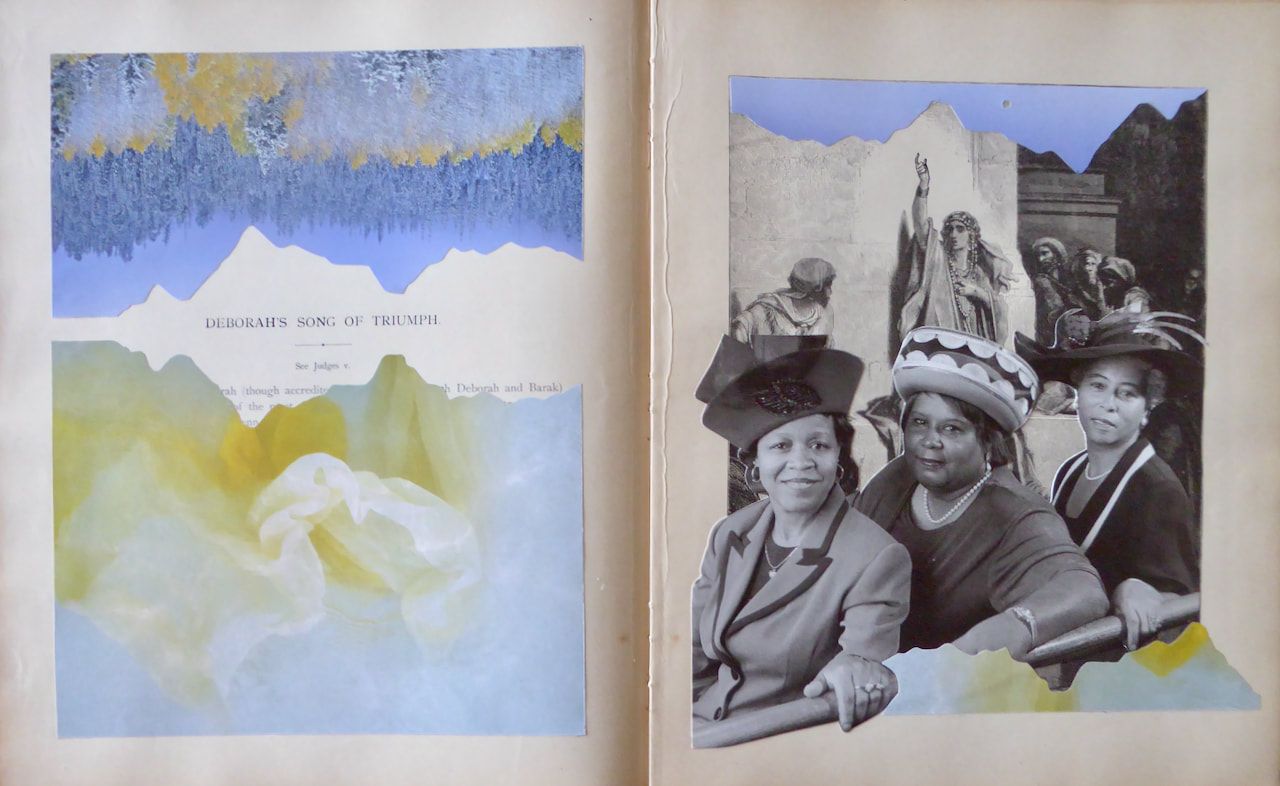

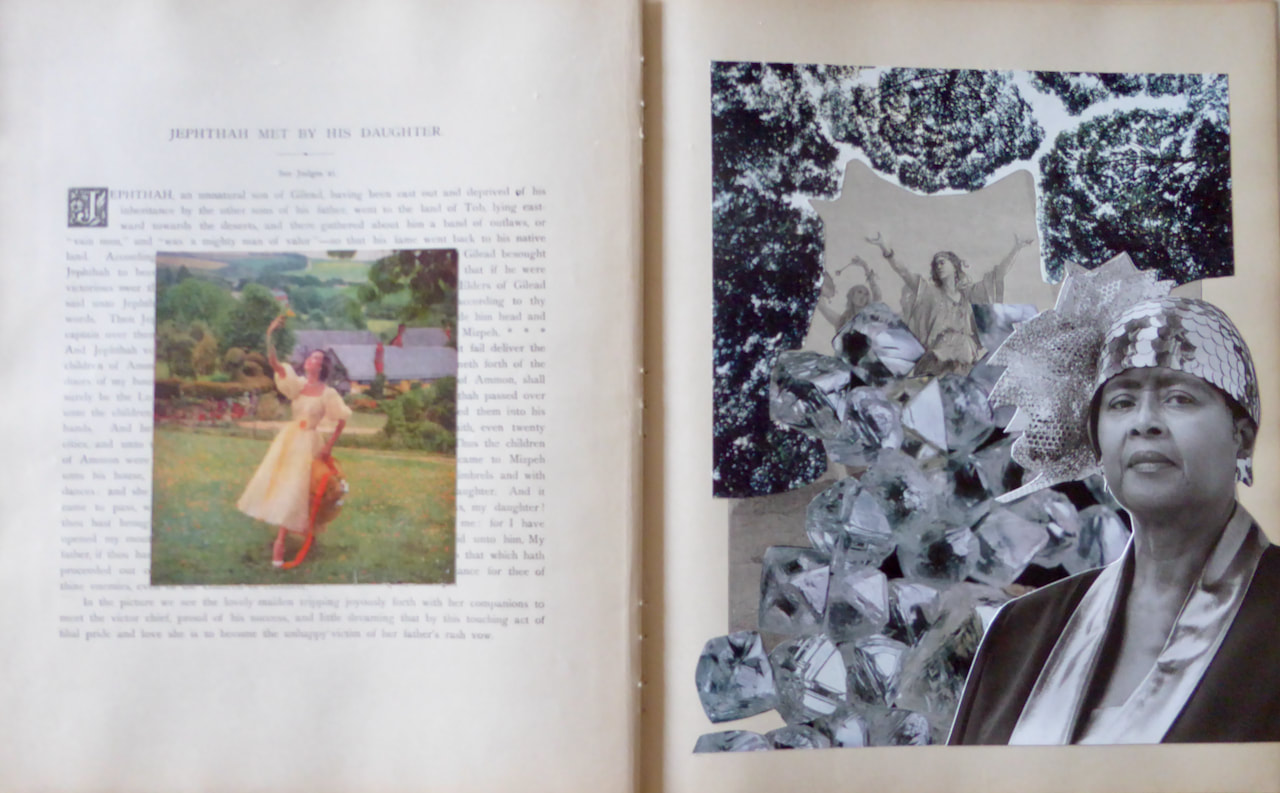

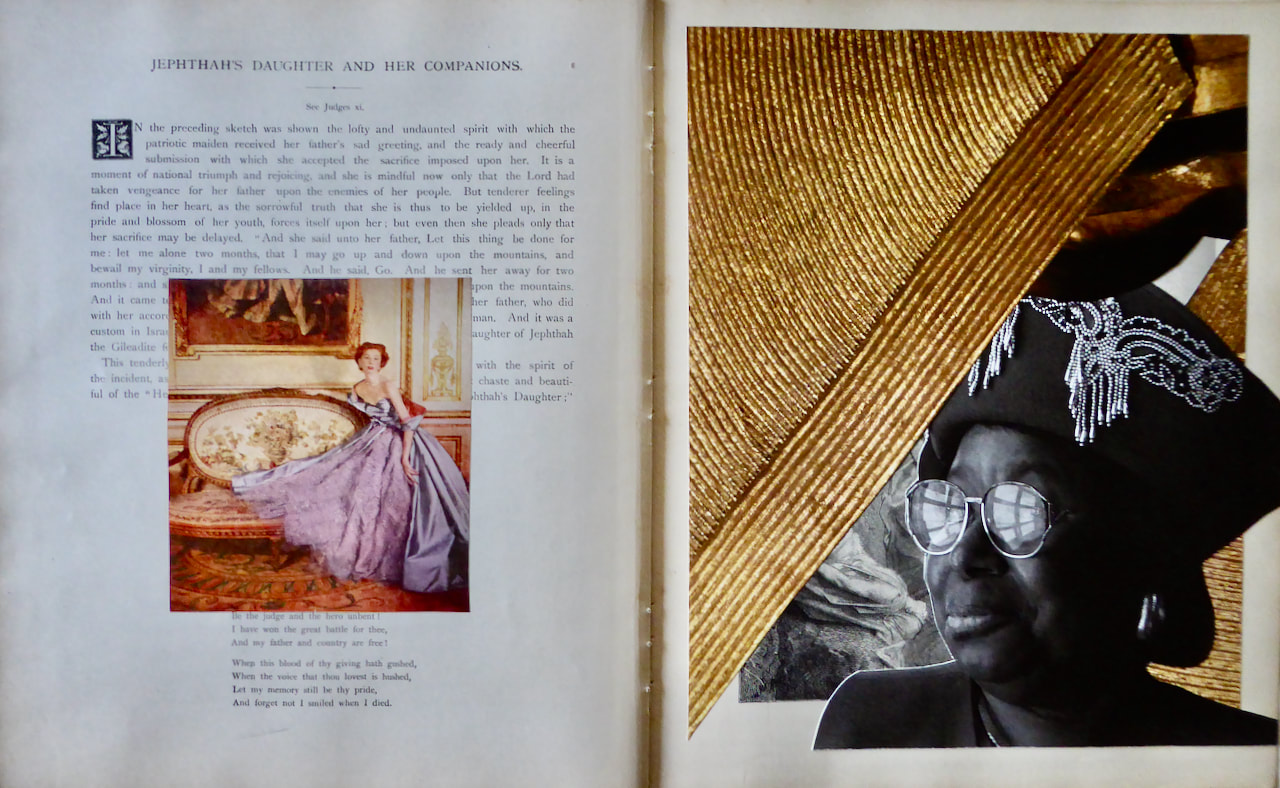

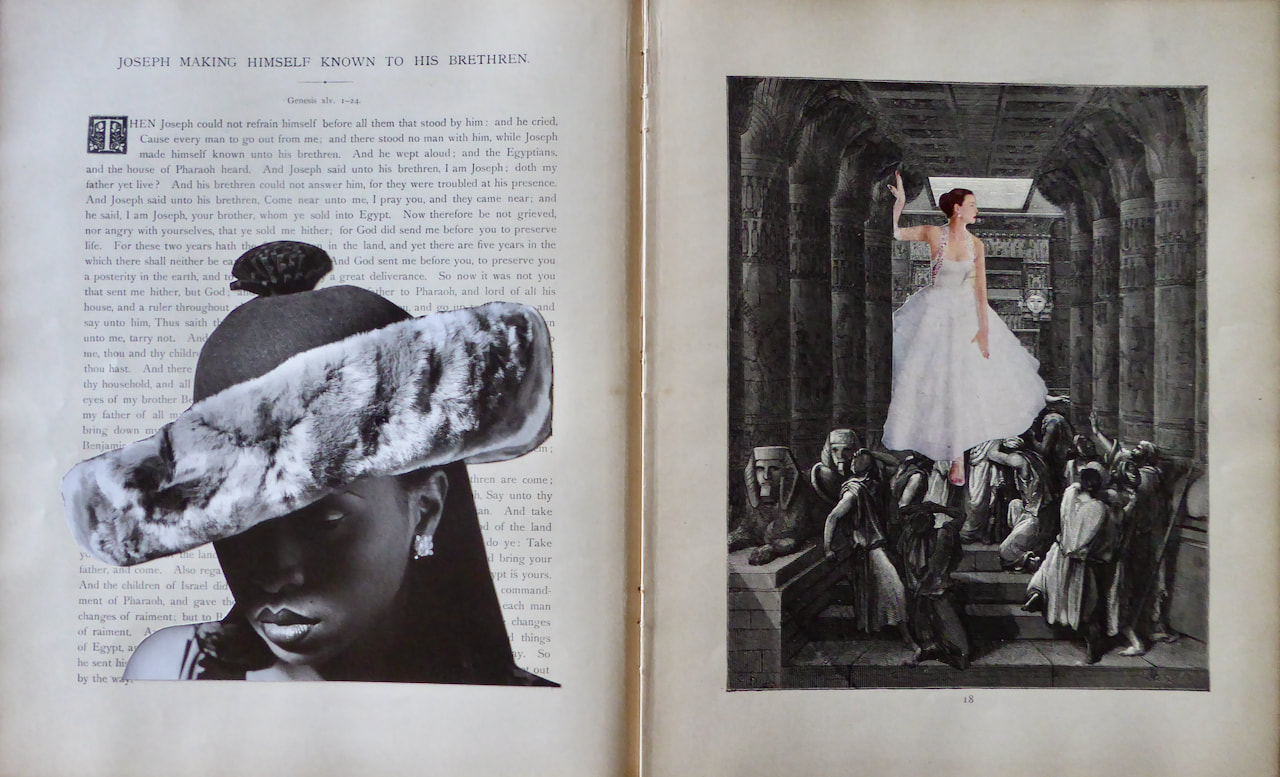

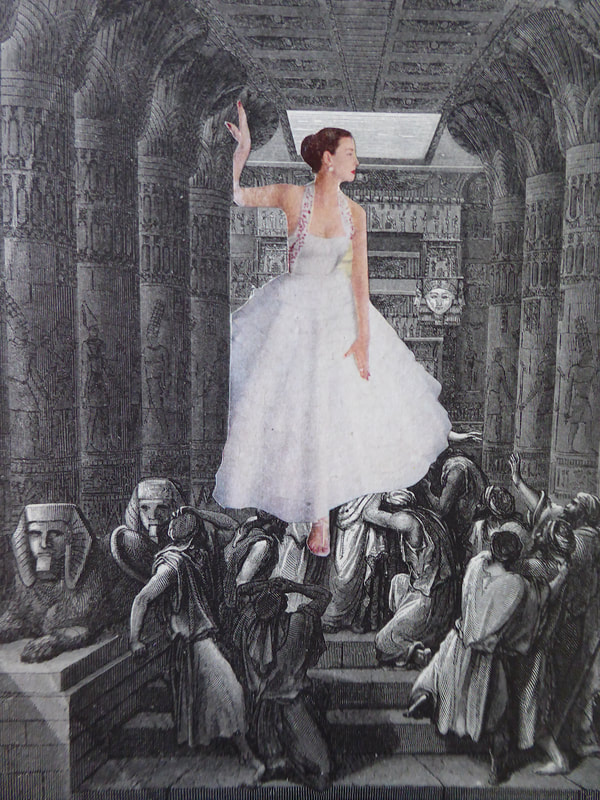

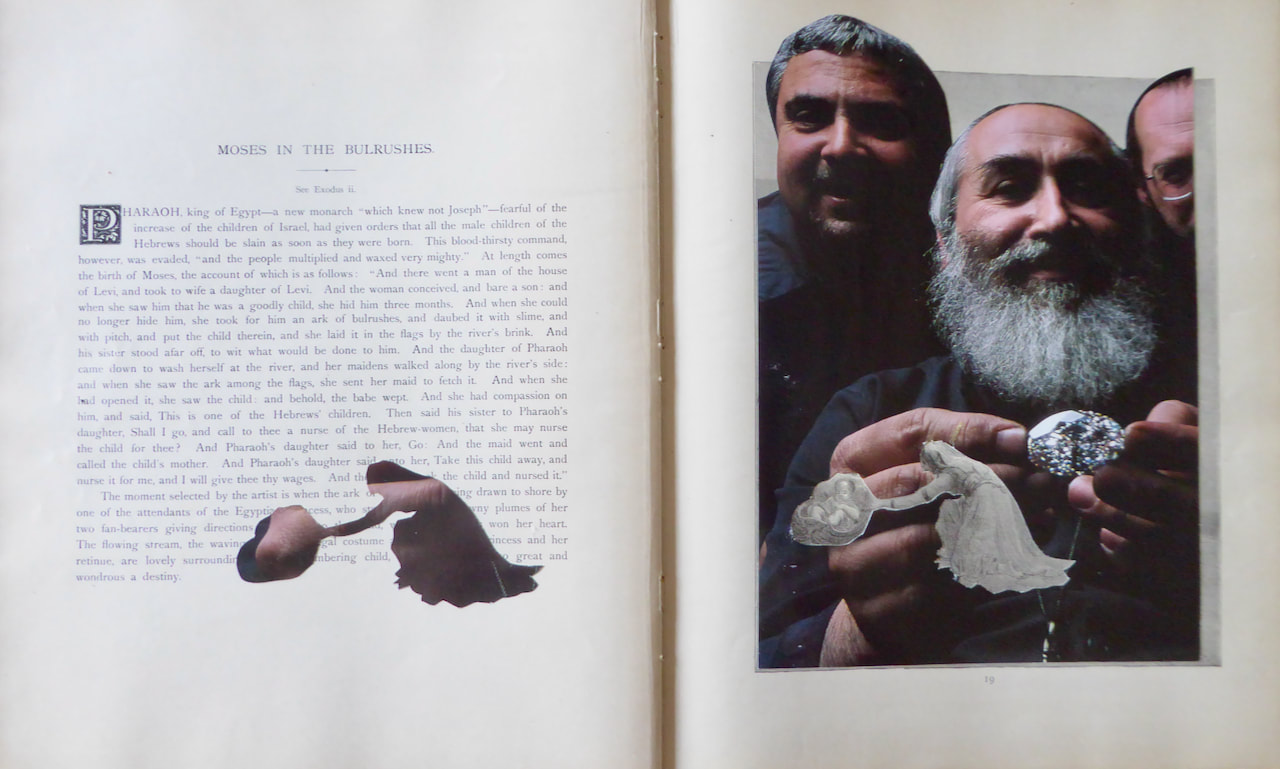

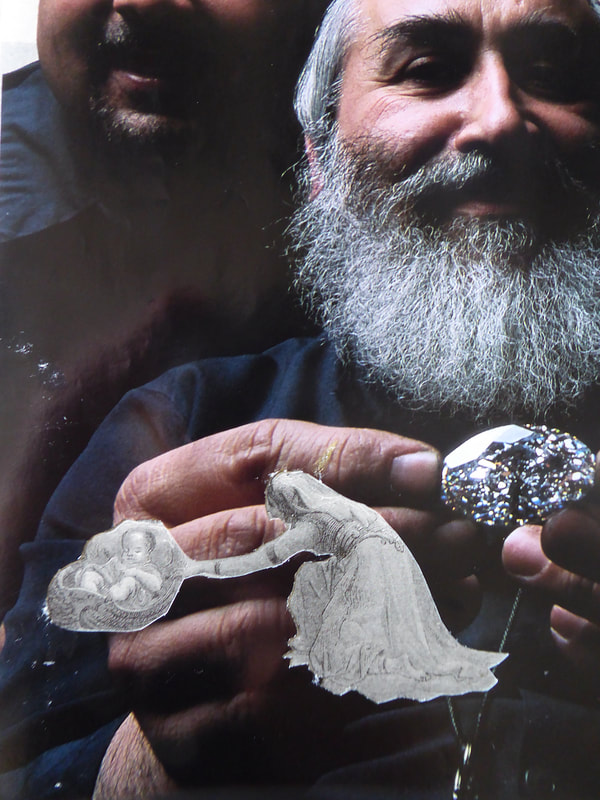

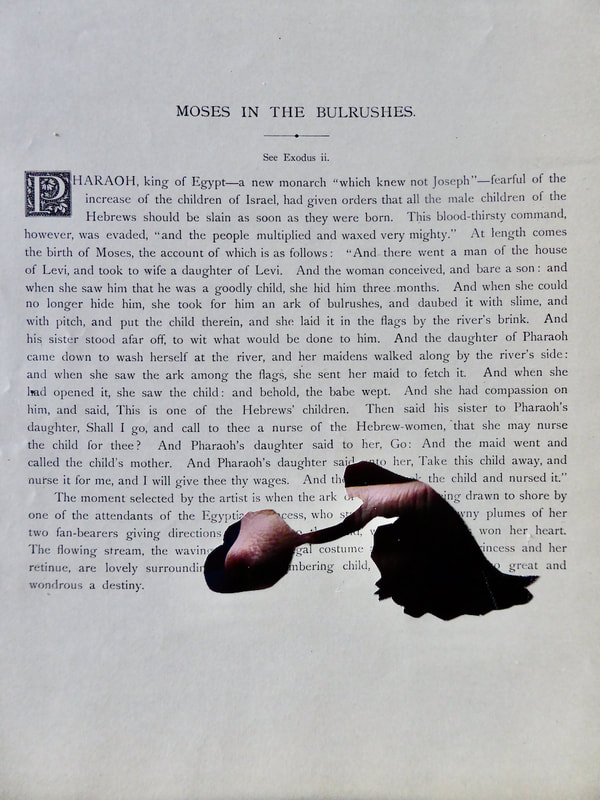

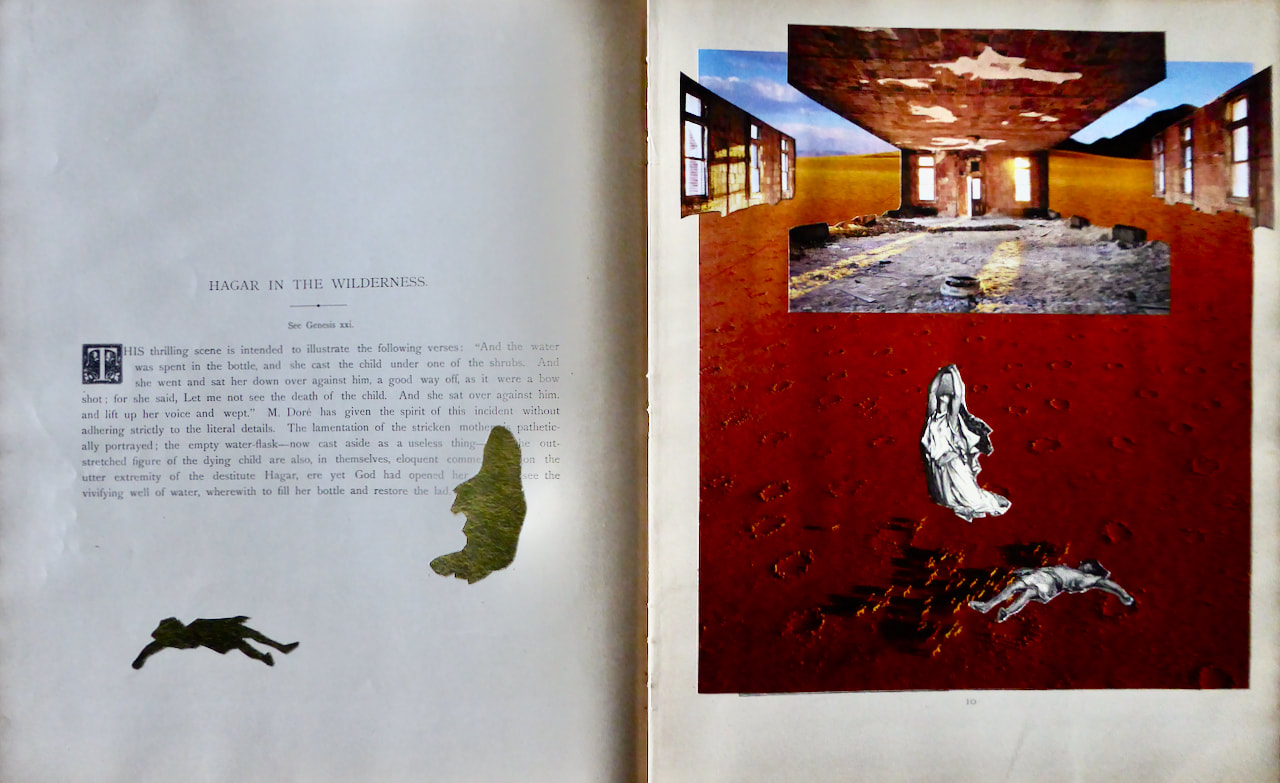

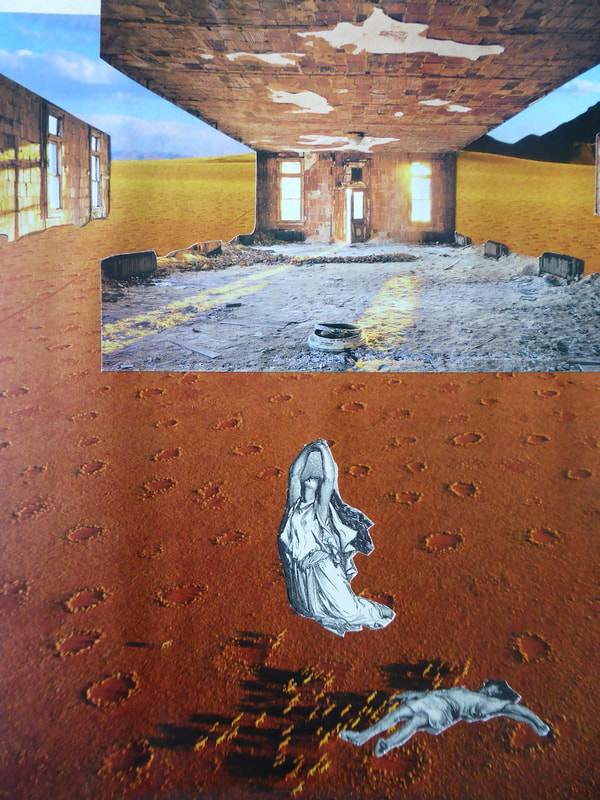

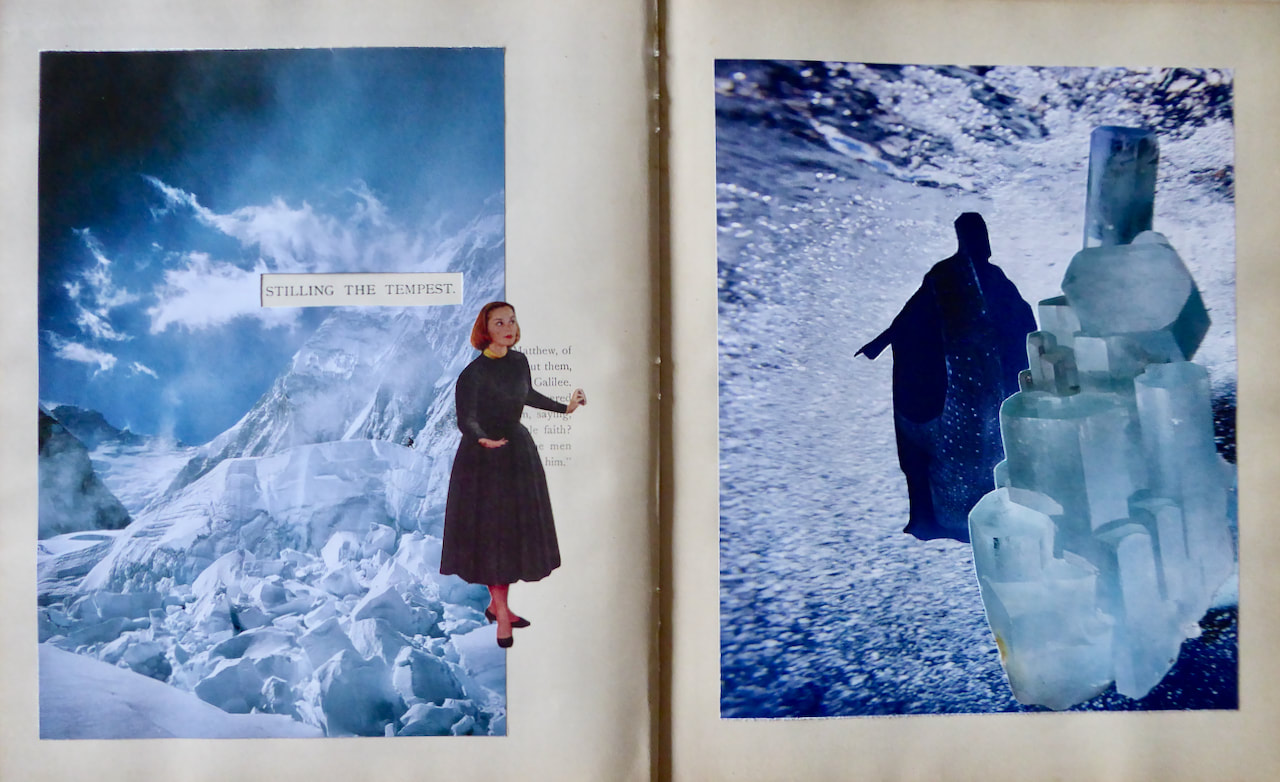

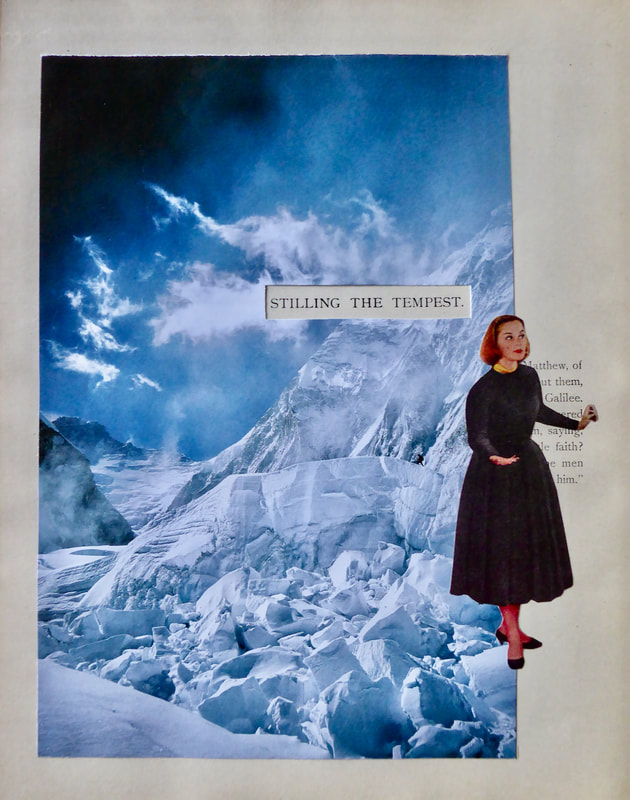

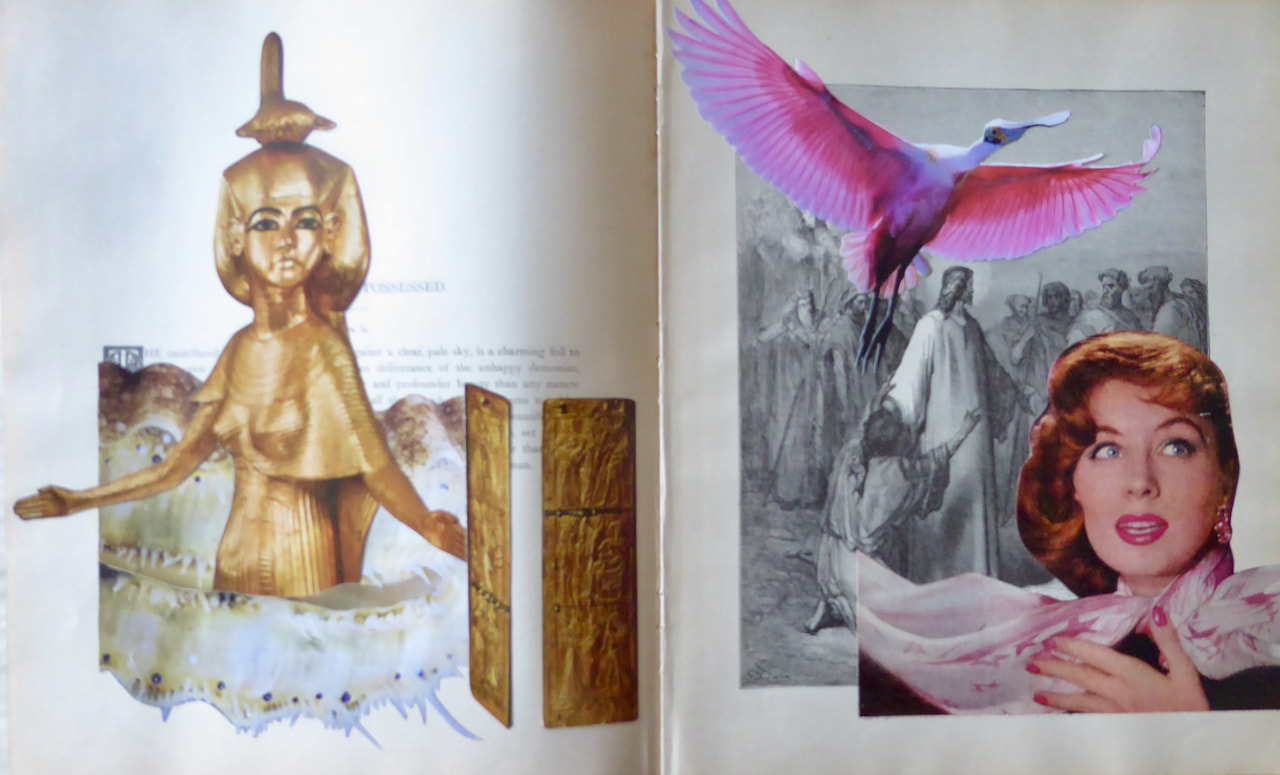

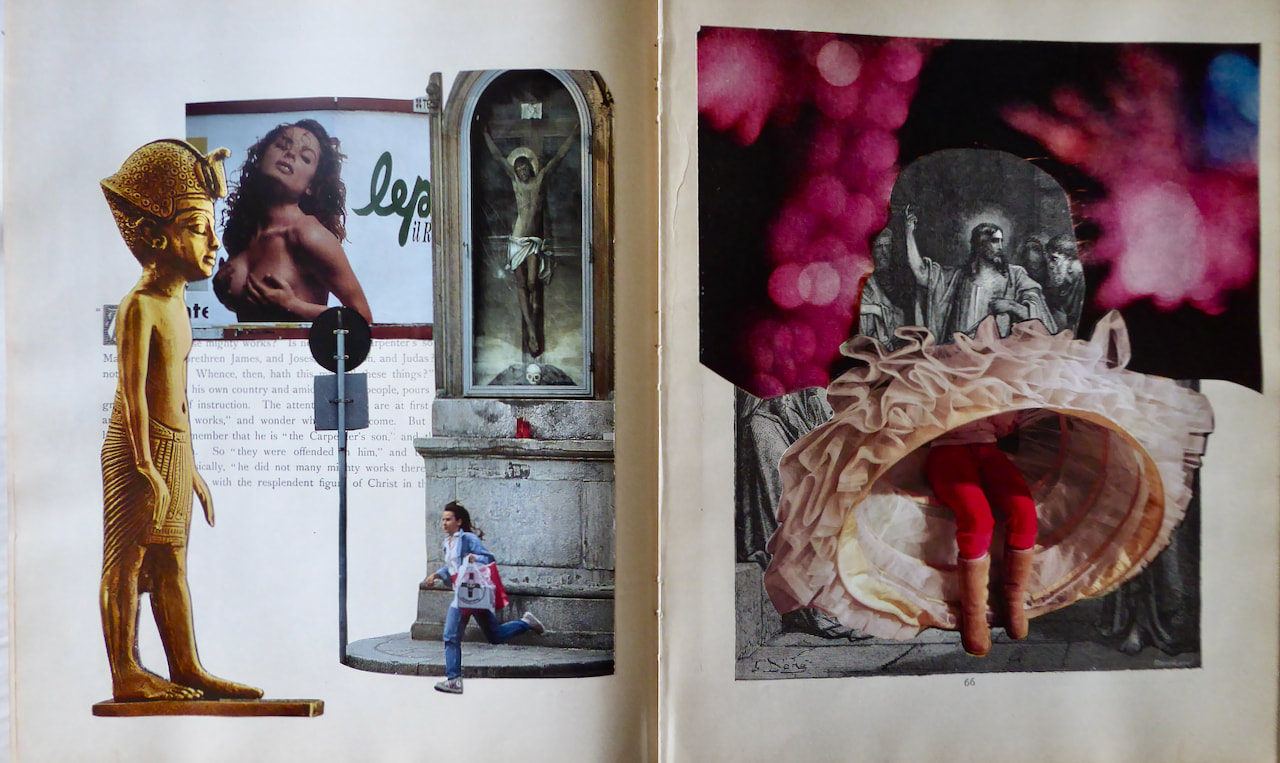

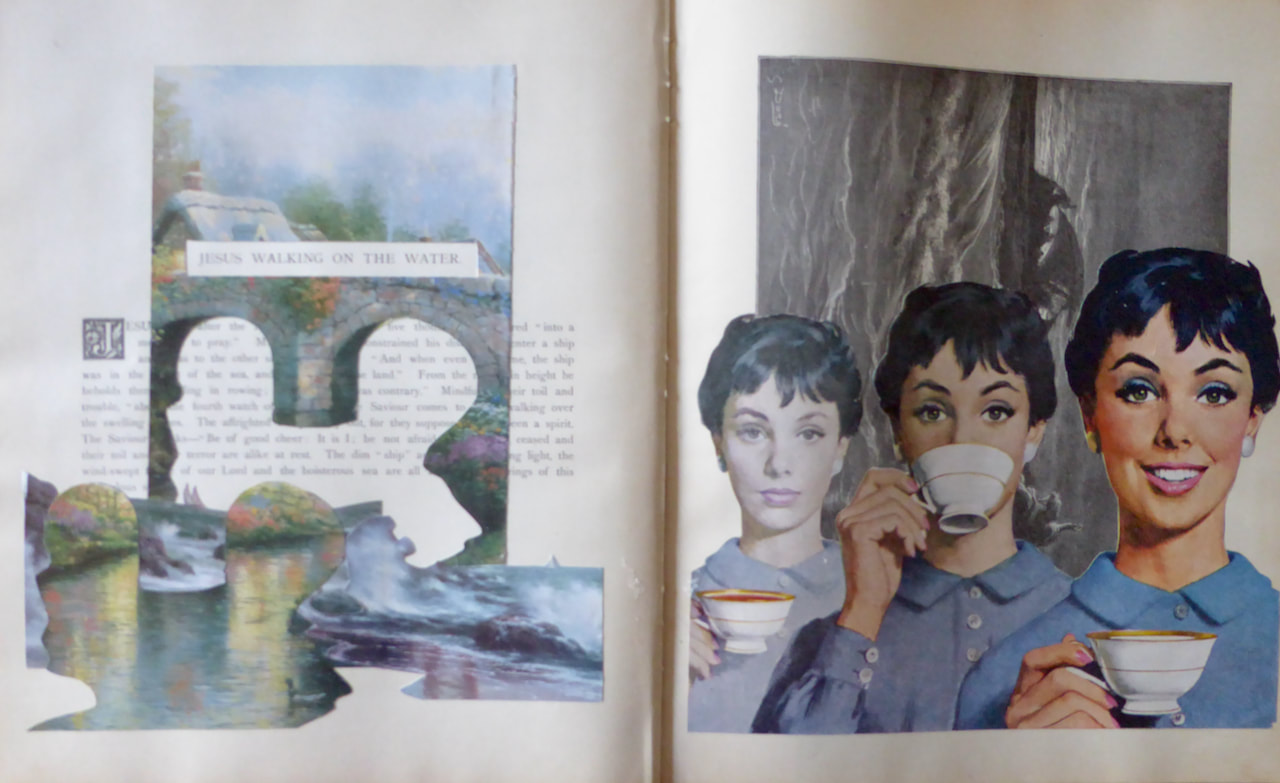

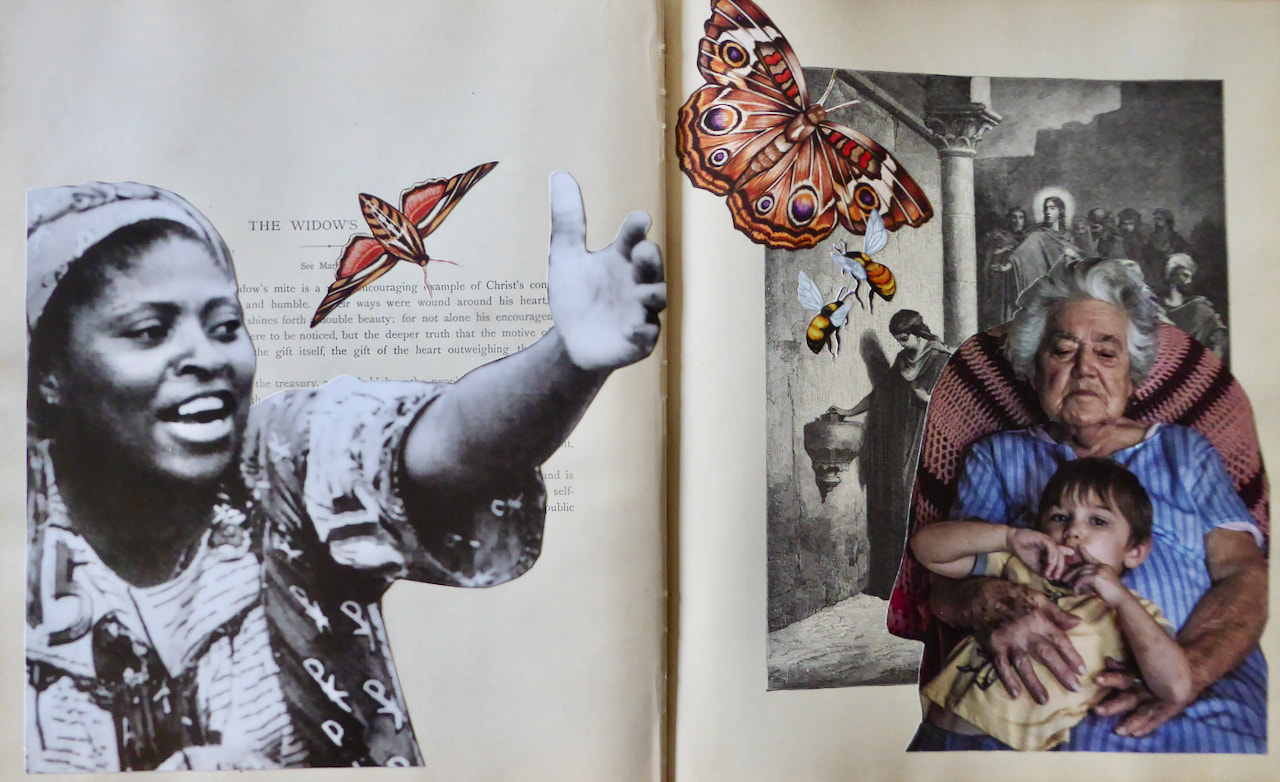

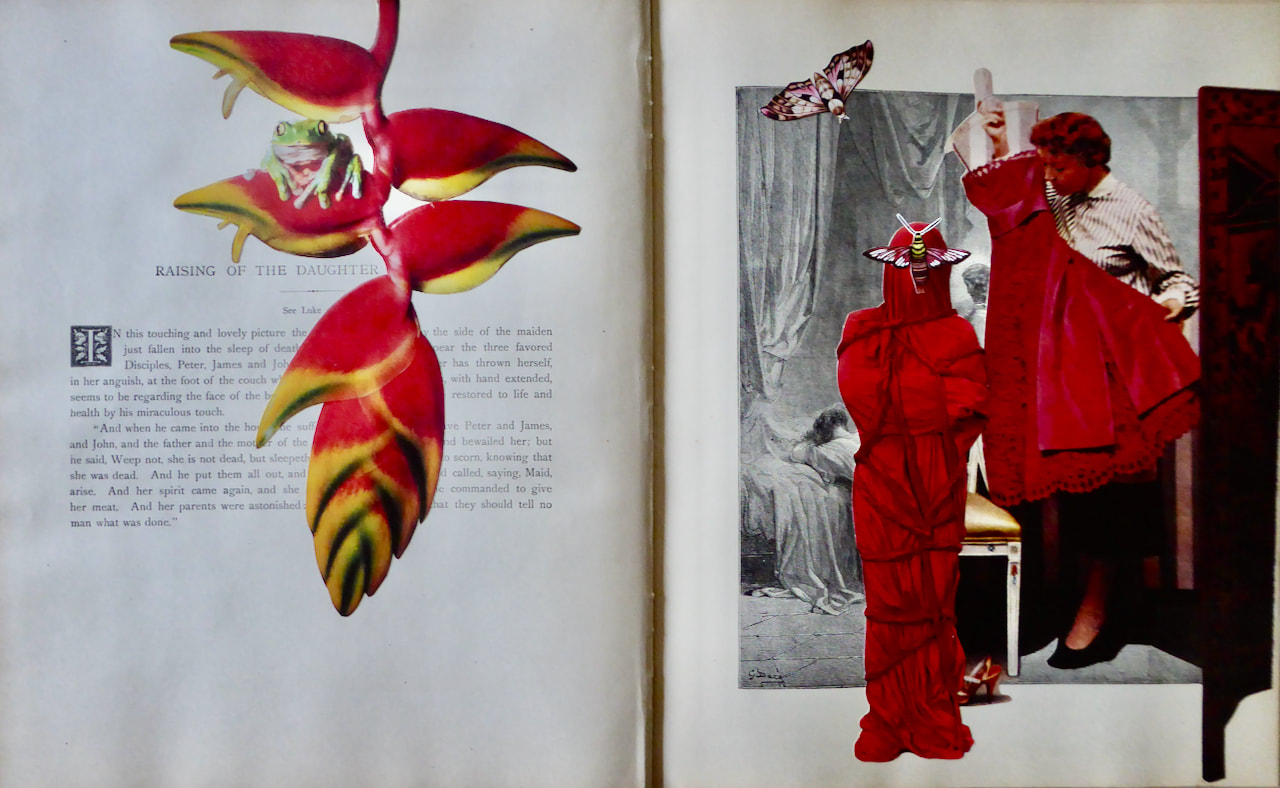

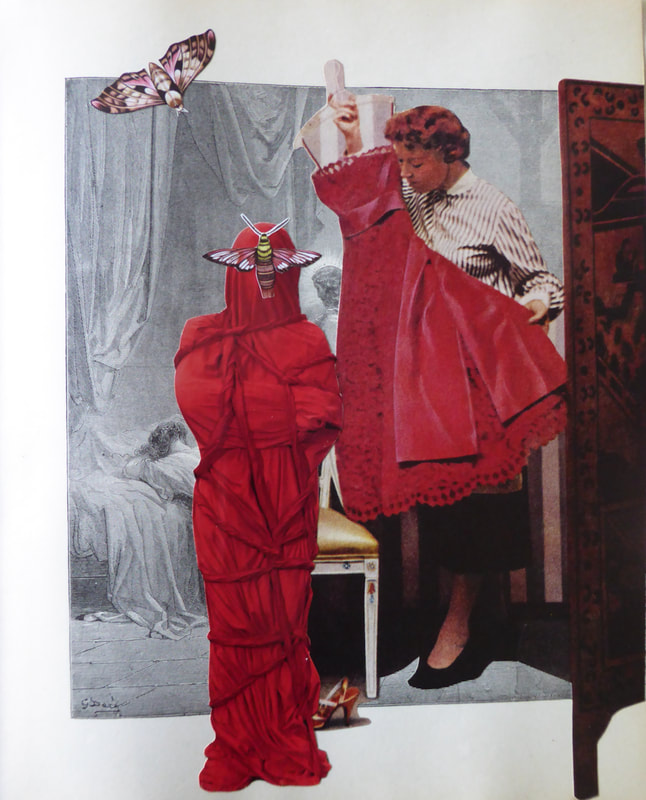

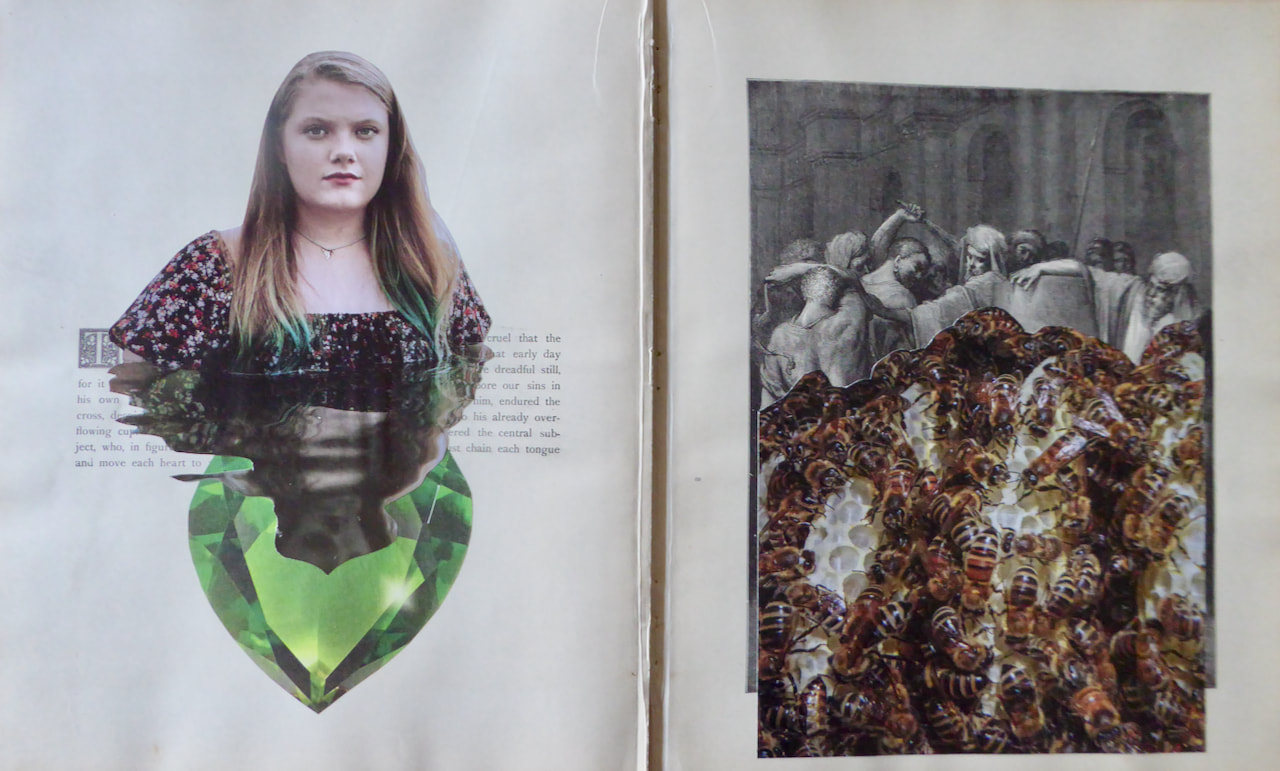

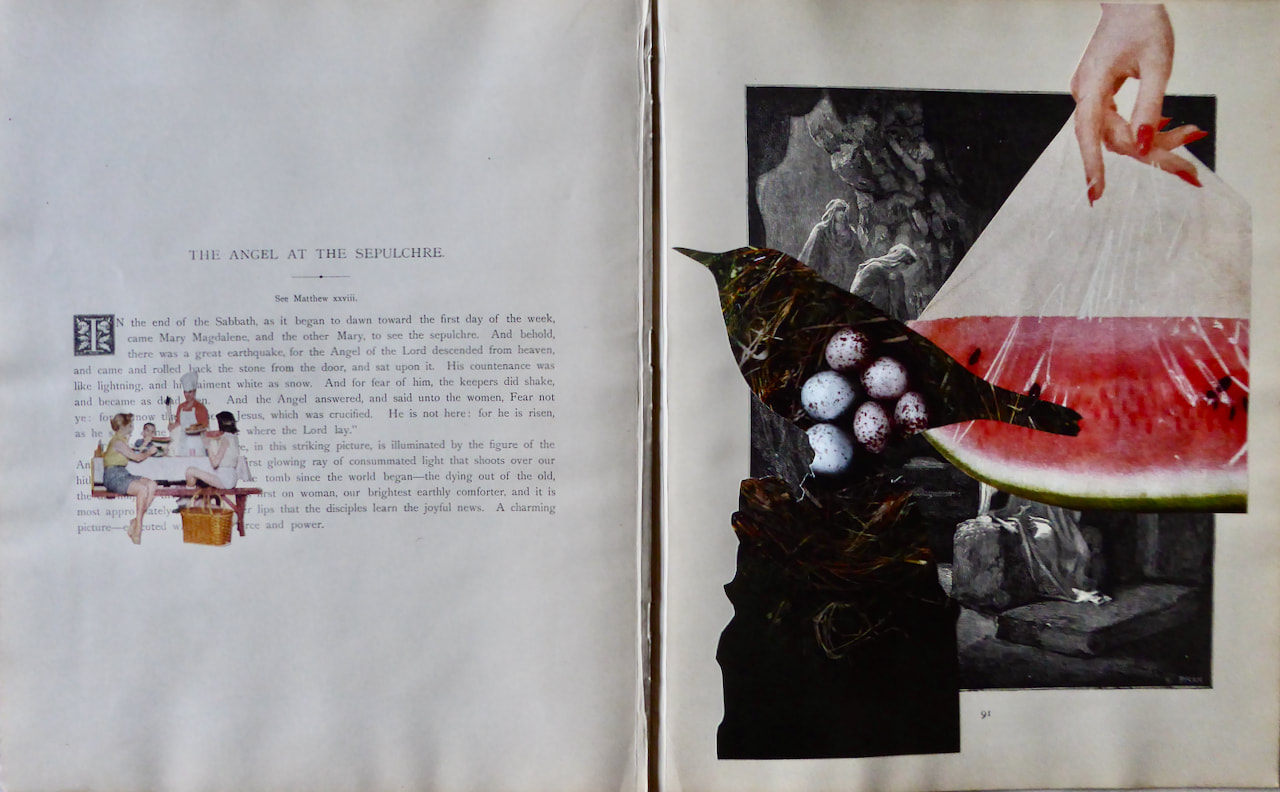

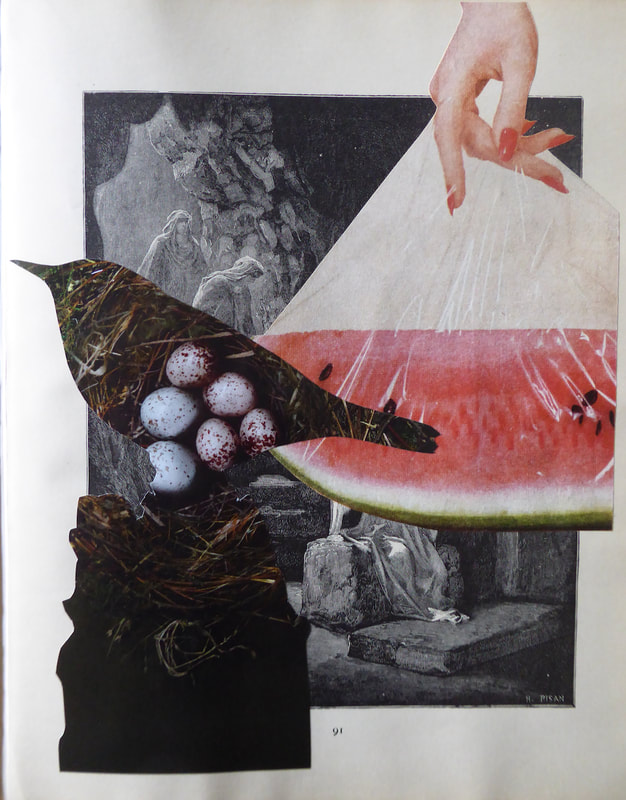

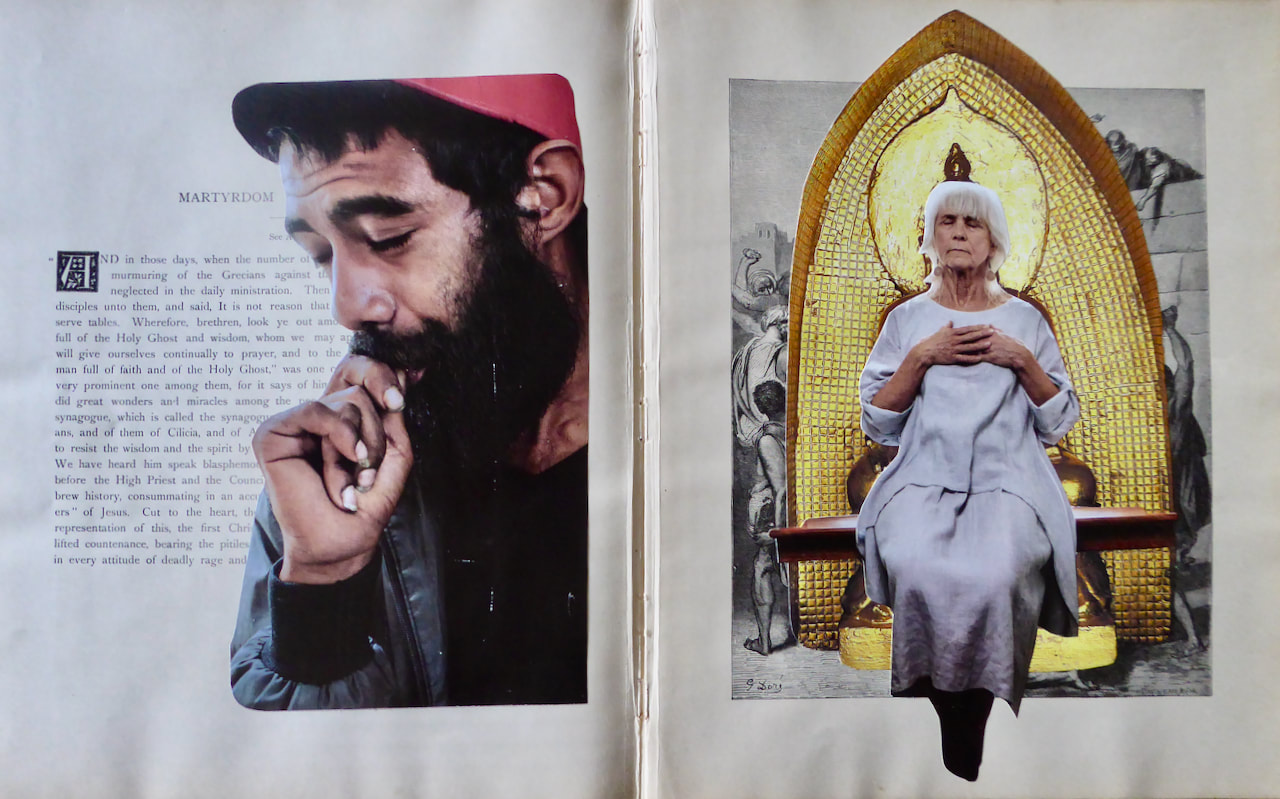

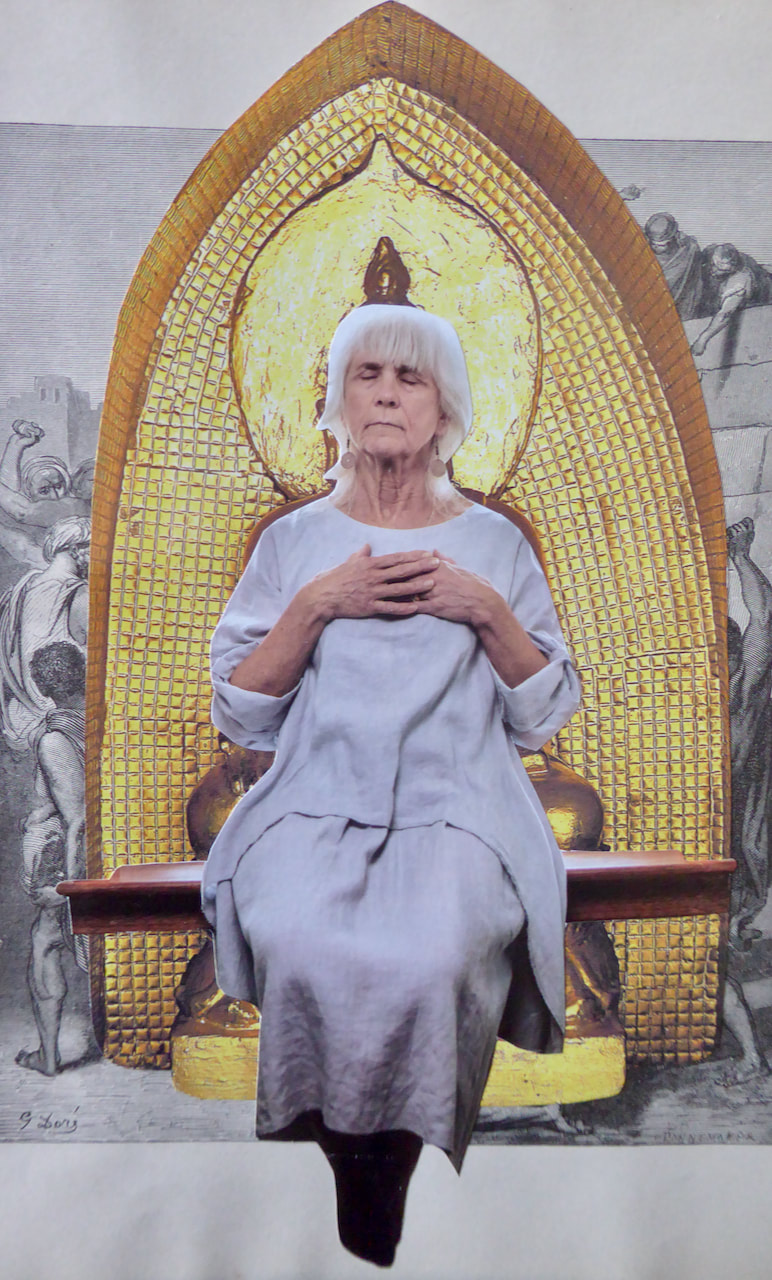

One woman irons a Bible in her studio, warmed by the heat of her woodstove. One woman’s embodied soul breathes the feminine, the Black and brown body, the pagan, and the animal back into the white-washed stories of the Patriarchs that dominate the 1890’s book and still shape the Trump administration context during which this work emerged (and the pandemic raged). Sometimes as I worked, I chuckled to myself, imagining the heart attacks this project might yet trigger in the fundamentalist teachers of my required high school Old and New Testament Bible classes. Who does she think she is?

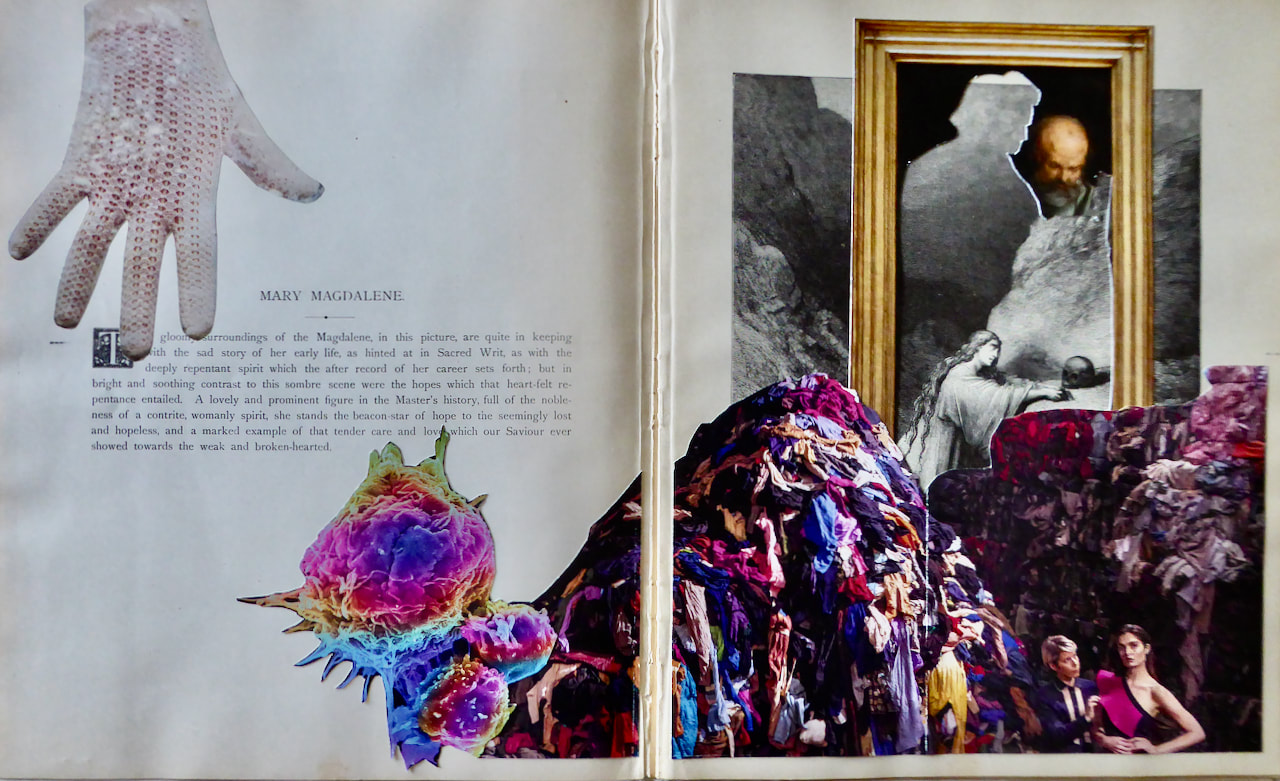

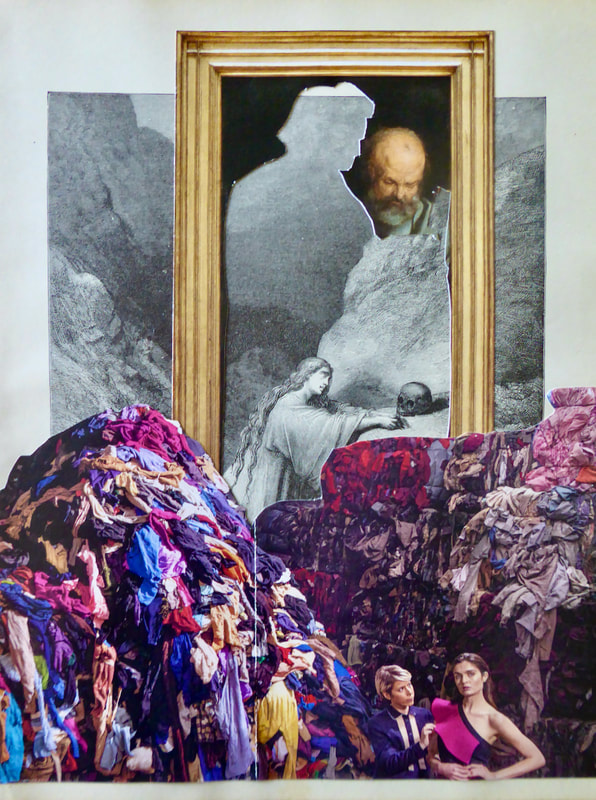

In my heart, (M)otherbible is an urgent and timely act of love, a mirror, an exorcism, and a series of surgical interventions – both excisions and grafts. I am approaching this Bible as I might a therapy case or a forensic investigation. Where are the wounds? Which systems are failing? Where are the resources to heal them? What needs to be released? Who’s missing? What are the traces remaining at the scene of the trauma? Who else might have been present at the scene as a silenced and disregarded witness?

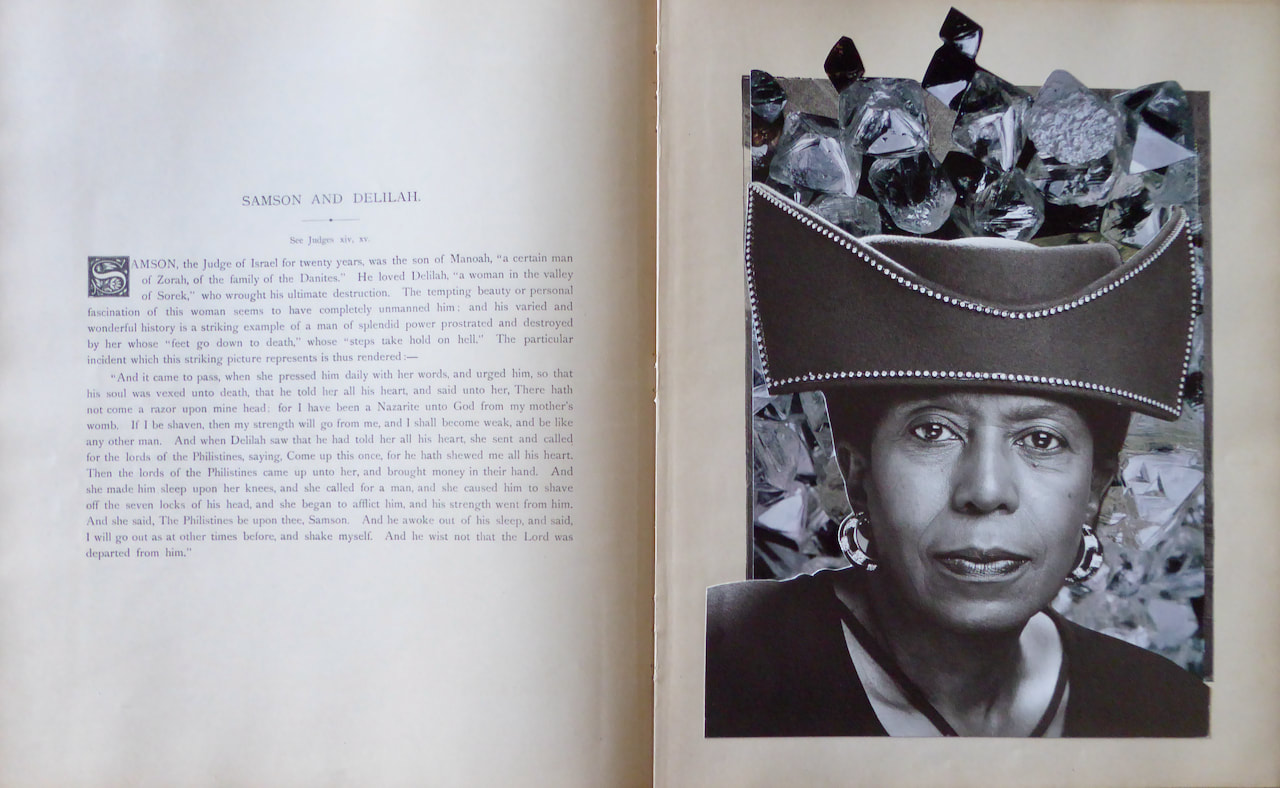

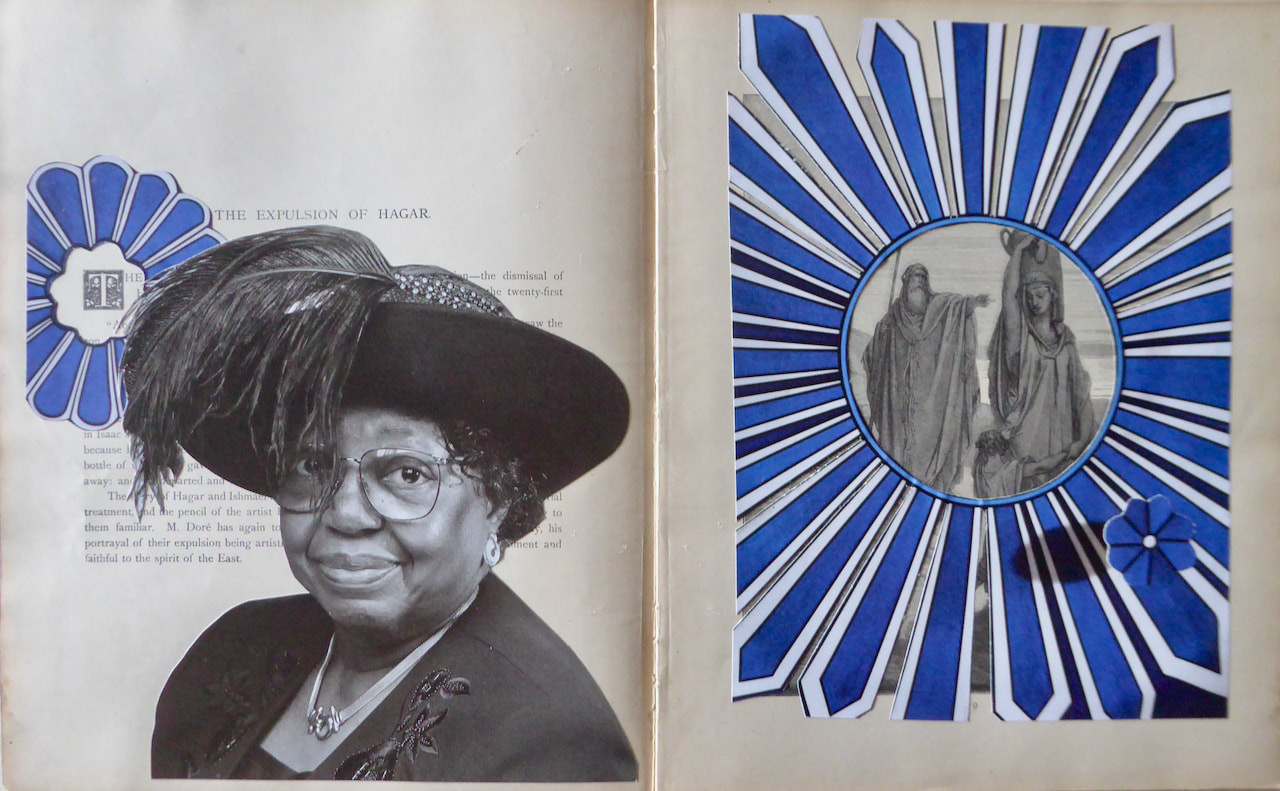

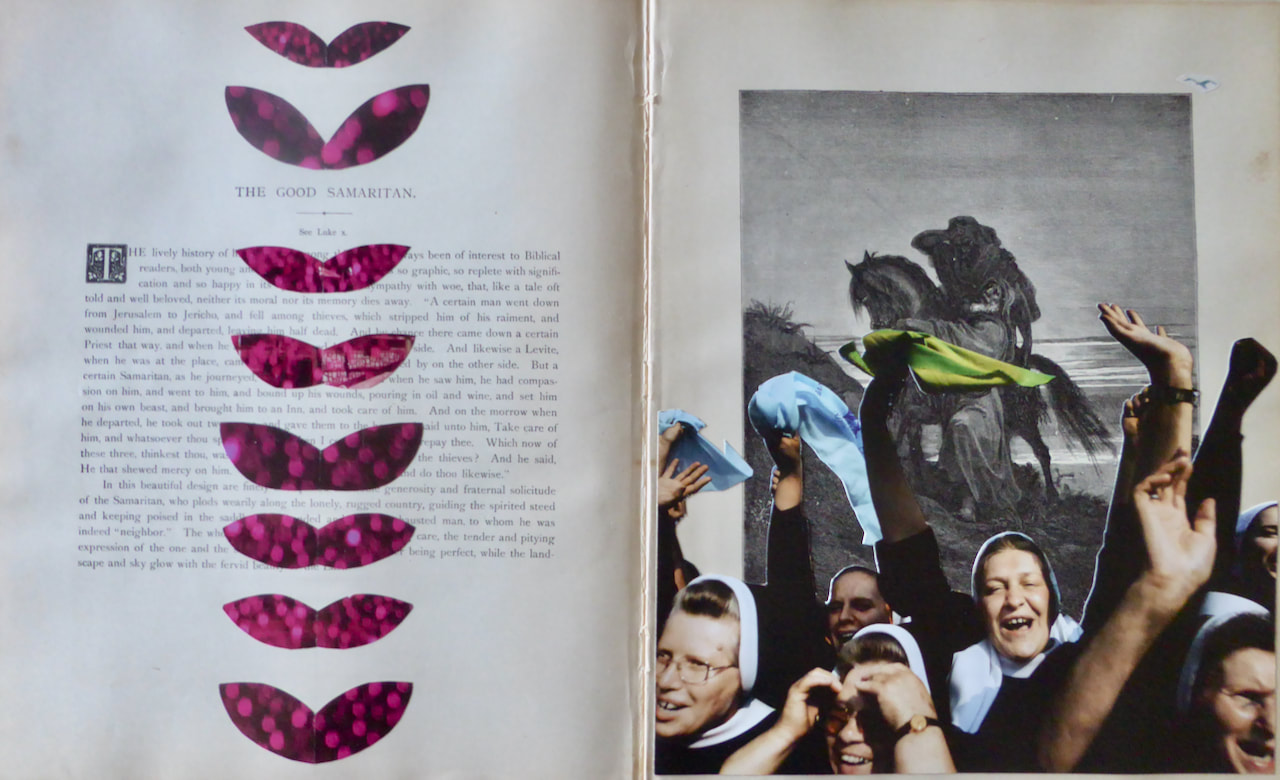

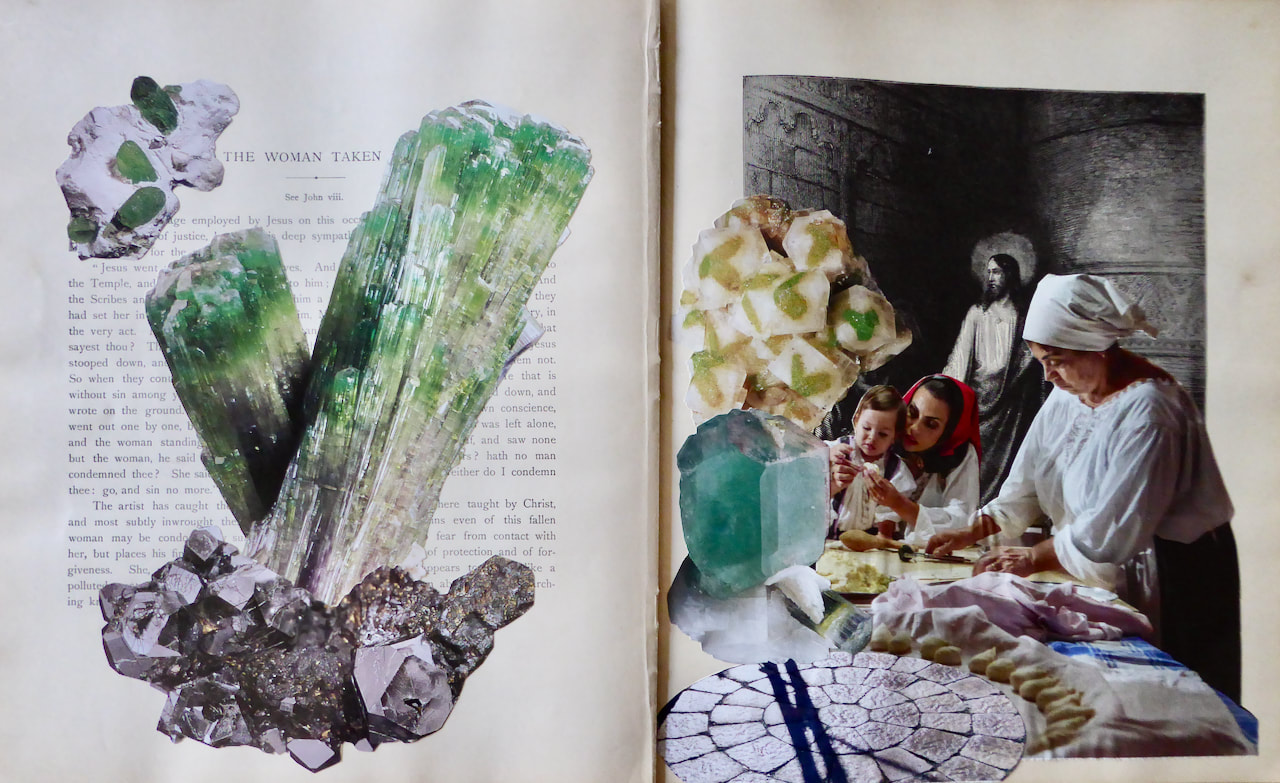

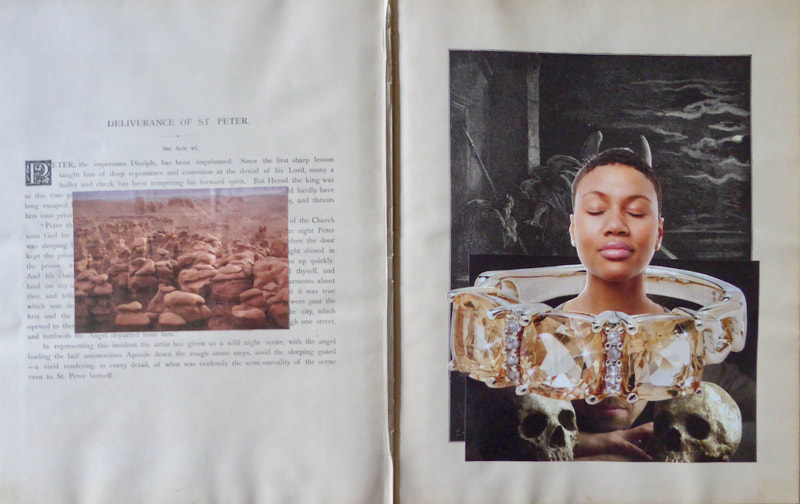

(M)otherbible is a working manifesto. The first spread I altered is now Paul Menaced by the [ ]. Originally it was the Jews, but (M)otherbible rejects anti-Semitism, reflexive misogyny, and blond-Jesus white supremacy. I listened to the images at my fingertips for new truths. I found Patriarchal Religion Menaced by Yoga, Germs, Cute Robots, and Women Minding Their Own Business. I found Women Wear Kerchiefs and Make Dumplings, While Men in Skirts Are Violent in the Distance. I found Wise Black Women Church Elders See You and They Are Not Fooled for One Minute. Some bits of the original text show through – religious zeal and hatred; in the Temple; seize him. The new work is a palimpsest, a hopeful monster that embodies adaptive mutations, while revealing enough of the past to underscore the urgency of change.

(M)otherbible Roots & Buds

(M)otherbible has ancestors through the ages: Hildegarde of Bingen’s illuminations of unitive consciousness, Jung’s Red Book, Martha Rosler’s House Beautiful / Bringing the War Home collages, among many others. She also has generous organ donors, including National Geographic and Life magazines, Michael Cunningham and Craig Marberry’s Crowns: Portraits of Black Women in Church Hats; and Thomas Kinkade’s Beside Still Waters: A Devotional. Cunningham’s photographs were immeasurably powerful to me in manifesting a strong, Black female gaze that witnesses the reader and the characters of Bible stories with equal wisdom. Kinkade’s paintings offered me a way to juxtapose gauzy religious sentimentality with powerful New Testament narratives. And the white women I borrowed from 1950’s issues of Life often seemed willing to clown the innocent/glamorous/temptress roles that Doré’s reading of the Bible had set aside for them years before.

All my borrowings mean that (M)otherbible is an uncopyrightable, unreproducible, unmarketable document. She is, as German speakers say, an Unikum. A blessing: if she is to have a life in the world, this unique copy of (M)otherbible will in time need to become an itinerant codex, with me as her equally wandering attendant. I imagine visiting congregations, covens, and groups of friends for story-tellings, truth-tellings, and dream-sessions, all inclining towards the sacred stories that arise spontaneously and become the ones we most need to hear. This in turn is a prayer for a post-pandemic world in which all beings may re-find possibilities for safe travel, free of contagion and political fracturing.

I give eternal thanks for the awareness in me that has brought forth (M)otherbible, in dialogue and interdependence with so many other awarenesses. I give thanks for this woman’s body, soul, and spirit. I give thanks for the ongoing work of reclaiming power, restoring, rewiring, rewriting, and coming into Being. Amen.

(M)otherbible Illuminatrix

Julie Püttgen, illuminatrix of the (M)otherbible, is an artist and therapist specializing in expressive and somatic approaches. A committed meditator since 1995 and former Buddhist nun, she facilitates retreats and programs exploring the intersections of Art (creativity) and Dharma (applied insight). (M)otherbible is an expression of her life-long passion for contemporary, embodied sacred-ordinary art-making. Her projects are online at www.everyday-regalia.com and www.108namesofnow.com.

Special thanks to Sarah Smith, Deborah Howe, and Lizzie Curran of the Dartmouth Book Arts Workshop, who offered their invaluable advice as I re-bound (M)otherbible.

Julie Püttgen

Lebanon, NH

October, 2020

There was a blacksmith at the flea market in Fairlee, Vermont who sold beautifully honed and restored tools – antique double-headed axes, hatchets, pickaxes – all heavy, deadly-looking, and powerful. Secretly, I wanted an axe, but something instead pulled me towards a beat-up, nineteenth-century Gallery of Bible Stories laying on an old blanket in the stall next door. Story of my life. Its covers were falling off. It had wild Gustave Doré engravings and beautiful gilt edges. I haggled the seller down to twenty bucks and walked off with this strange prize under my arm, feeling vaguely haunted among people looking at trivets and buying jam on that bright July morning. Now what?

Wrapped in archival glassine, the Bible sat on my bookshelf for a decade. I wanted to do something with it, but I wasn’t sure what. Cannibalize it? Paint it? Collaborate with others to create a communally altered book? Nothing resonated enough for me to move forward wholeheartedly. Whatever I chose, I knew I wanted to commit to a single process and follow through with it for the entire artifact.

The COVID-19 pandemic hit around the same time I that was completing a yearlong practice of sewing monthly thangkas – Tibetan-inspired scroll-paintings – co-arising from found everyday fabrics and Buddhist texts chosen by members of the women’s Art/Dharma group I’d founded a year earlier. Now in self-isolation at home, and with a second year of Art/Dharma about to begin, I was ready for a new sacred/ordinary art assignment.

(M)otherbible is Born

I started looking more closely at the structure and content of my flea market Doré Bible. Its pages – as is often true for industrially-produced paper of that era – are brittle at the edges and spine. They are grouped into signatures (bundles) of four folios (two-page spreads) each. The original binding used metal staples – now rusty – to attach the signatures to a gluey spine. Its thick, embossed covers had torn away from the text block. Each illustration and its accompanying text are printed on one side of the sheet; the verso is blank. Between the pages, I found traces of dead insects and long-gone four-leaf clovers.

With my hands, I started to imagine a dual process: I would repair the book and rework it at the same time, using tools and materials that were already in my studio. A friend had given me Japanese tissue paper that I could use to reinforce the page-creases; another friend had brought me old cotton sheets that I could use to protect the pages as I ironed the creases and mildew out of them. I had a good supply of acid-free glue, wax paper, and cloth-covered brick weights. I also had piles of printed matter for collaging, foraged from the dump, the library discard pile, the recycling bin, and other not-quite-trash.

So I started the one-woman Pandemic Bible Study that became (M)otherbible. I decided to re-work two signatures each week. This meant creating that week’s collages (right-brain intuition), as well as mending the spine-creases of the following week’s signatures (left-brain sequential logic), so the tissue repairs would dry in time. Three days a week, I would go to my office in a mostly deserted building and see my therapy clients via Zoom. Four days a week, Bible Studies, remote 5Rhythms dance sessions, forest romps with my dogs, therapy, grocery store, supervision, repeat.

I have spent a lot of time in meditation retreat and studio production, so this improvised weekly rhythm felt quite natural to me. Yes, the heart of the pandemic carried devastating news; and, yes, I felt anchored by meaningful work.

I was and am quite fortunate in this.

One woman irons a Bible in her studio, warmed by the heat of her woodstove. One woman’s embodied soul breathes the feminine, the Black and brown body, the pagan, and the animal back into the white-washed stories of the Patriarchs that dominate the 1890’s book and still shape the Trump administration context during which this work emerged (and the pandemic raged). Sometimes as I worked, I chuckled to myself, imagining the heart attacks this project might yet trigger in the fundamentalist teachers of my required high school Old and New Testament Bible classes. Who does she think she is?

In my heart, (M)otherbible is an urgent and timely act of love, a mirror, an exorcism, and a series of surgical interventions – both excisions and grafts. I am approaching this Bible as I might a therapy case or a forensic investigation. Where are the wounds? Which systems are failing? Where are the resources to heal them? What needs to be released? Who’s missing? What are the traces remaining at the scene of the trauma? Who else might have been present at the scene as a silenced and disregarded witness?

(M)otherbible is a working manifesto. The first spread I altered is now Paul Menaced by the [ ]. Originally it was the Jews, but (M)otherbible rejects anti-Semitism, reflexive misogyny, and blond-Jesus white supremacy. I listened to the images at my fingertips for new truths. I found Patriarchal Religion Menaced by Yoga, Germs, Cute Robots, and Women Minding Their Own Business. I found Women Wear Kerchiefs and Make Dumplings, While Men in Skirts Are Violent in the Distance. I found Wise Black Women Church Elders See You and They Are Not Fooled for One Minute. Some bits of the original text show through – religious zeal and hatred; in the Temple; seize him. The new work is a palimpsest, a hopeful monster that embodies adaptive mutations, while revealing enough of the past to underscore the urgency of change.

(M)otherbible Roots & Buds

(M)otherbible has ancestors through the ages: Hildegarde of Bingen’s illuminations of unitive consciousness, Jung’s Red Book, Martha Rosler’s House Beautiful / Bringing the War Home collages, among many others. She also has generous organ donors, including National Geographic and Life magazines, Michael Cunningham and Craig Marberry’s Crowns: Portraits of Black Women in Church Hats; and Thomas Kinkade’s Beside Still Waters: A Devotional. Cunningham’s photographs were immeasurably powerful to me in manifesting a strong, Black female gaze that witnesses the reader and the characters of Bible stories with equal wisdom. Kinkade’s paintings offered me a way to juxtapose gauzy religious sentimentality with powerful New Testament narratives. And the white women I borrowed from 1950’s issues of Life often seemed willing to clown the innocent/glamorous/temptress roles that Doré’s reading of the Bible had set aside for them years before.

All my borrowings mean that (M)otherbible is an uncopyrightable, unreproducible, unmarketable document. She is, as German speakers say, an Unikum. A blessing: if she is to have a life in the world, this unique copy of (M)otherbible will in time need to become an itinerant codex, with me as her equally wandering attendant. I imagine visiting congregations, covens, and groups of friends for story-tellings, truth-tellings, and dream-sessions, all inclining towards the sacred stories that arise spontaneously and become the ones we most need to hear. This in turn is a prayer for a post-pandemic world in which all beings may re-find possibilities for safe travel, free of contagion and political fracturing.

I give eternal thanks for the awareness in me that has brought forth (M)otherbible, in dialogue and interdependence with so many other awarenesses. I give thanks for this woman’s body, soul, and spirit. I give thanks for the ongoing work of reclaiming power, restoring, rewiring, rewriting, and coming into Being. Amen.

(M)otherbible Illuminatrix

Julie Püttgen, illuminatrix of the (M)otherbible, is an artist and therapist specializing in expressive and somatic approaches. A committed meditator since 1995 and former Buddhist nun, she facilitates retreats and programs exploring the intersections of Art (creativity) and Dharma (applied insight). (M)otherbible is an expression of her life-long passion for contemporary, embodied sacred-ordinary art-making. Her projects are online at www.everyday-regalia.com and www.108namesofnow.com.

Special thanks to Sarah Smith, Deborah Howe, and Lizzie Curran of the Dartmouth Book Arts Workshop, who offered their invaluable advice as I re-bound (M)otherbible.

Julie Püttgen

Lebanon, NH

October, 2020