|

buy nothing.

repair. waterproof. clean up. sweep out the dog-hairs & old seeds. at the dump, find four useful books & a crate full of stars. Here's an article about my brilliant friend Allison Rentz, at play in the world. The fact that she's generating so much discomfort on all sides through this simple idea tells me she's really onto something. On the Facebook page for the project, Rentz makes reference to an incident in which an artist she admired called a tip “an insult,” adding, “I asked her if she ever accepts money for her art and [she] said that she will sell it for $5,000 and that a dollar is an insult. I don’t think she understood the project, but it was a bit of a heated discussion...” Having worked in food service & as a by-donation meditation teacher, I love the idea of Tip Your Artist. It's humanizing. it means we have to take responsibility for what we are doing when we are at a gallery opening, what we are doing when we tip someone, and what we are doing when we put a $5000 price tag on our paintings.

Yesterday, I had a choice between buying myself a cookie to go with lunch & using that same money to tip the young woman working behind the counter. I chose the latter & it felt good. it said: I see you & that cookie's not worth breaking the cycle of generosity that's brought me here. Be well & so shall I. When I got on the train, the first thing I saw was that this was a terrible, isolating Western train. I burst into tears, in the confines of my blue plastic coop, designed to keep me private, separate, uncontaminated, and bored. O tomato-smugglers of Uzbekistan, where are you? Snotty, pink-cheeked children, flirting pensioners, even stinging tomato-cockroaches, where are you?

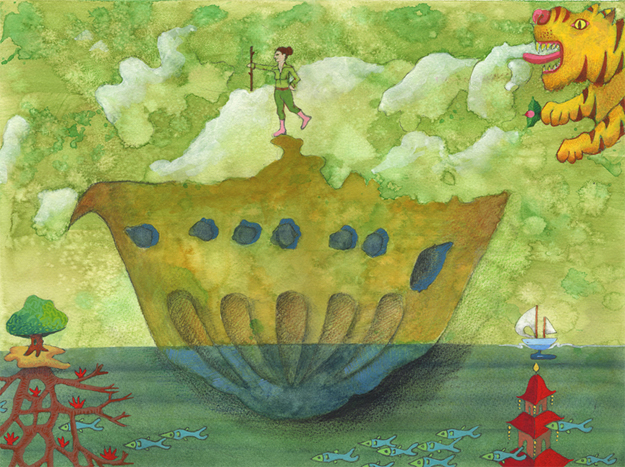

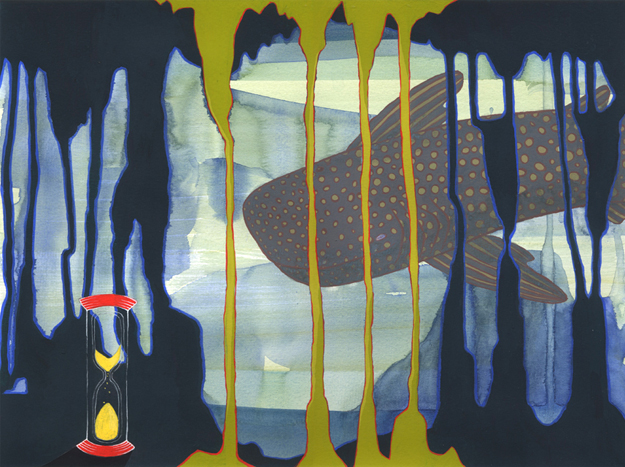

I mean, it's not like I wanted to stay in Belarus. Belarus blew, and I'd never planned to be there in the first place, but this, this stupid chicken-house on rails, this was an insult to travel and to travelers everywhere. The further West I got, the clearer it became to me that the giant everyone in a bus, you too goats! aesthetics of the road were dissolving behind me. I was back on the ground that had spawned me, the boredom of the suburbs, the secret dread of privacy, the stiff hierarchies of who we speak to & who we don't speak to. Blue plastic walls, blue carpet, blue soundproof windows. Room for one or maybe two. Smoothed-out landscapes, passing, passing rain-smoothed and bland. Danger averted drunkenness hidden. No space for life to unfold an offer of marriage to some cousin somewhere, no jars of jam passing across the aisle, no Jesus Christ Superstar mile after mile of birches eating sketchy sausages under the bleary gaze of a Russian soldier helically gulping down his daily liters of vodka. What I saw when I got on the train was: this is the pickle we're in, in the West, and you're going to have to work on it with all your strength. I didn't exactly realize that's what I saw, because I was too busy crying over this awful blue cell. It took about twenty years for me to see what I saw, actually. Twenty years of flirting with maybe it's true? Maybe safety IS what I want, a separate sense of smoothly going along towards my culturally-appointed goals? But, no. No such zip locked destinations. I wanted the open-carriage trains of China & Mongolia & Russia back. I wanted danger and presence back - the sense of all being on this one moving thing together. All of us smuggling ourselves, our heavy bodies across the world. On the train, I read Solzhenitsyn's Cancer Ward. I read Yourcenar's Mémoires d'Hadrien. I listened to the rails click clack with hundreds of pairs of ears also listening. Lives unfolding together - breathing this travelers' air. Several times, I fucked up, and found myself on not-the-right-train. The one I missed because I meditated for too long, sitting in my unmarked Moscow hotel room is the one that landed me in Belarus. The one I gave up because I decided Bukhara was too beautiful for only one day is the one that landed me on the tomato smugglers' special across Central Asia - a train so slow a grandfather could get on board in a village with his two grandchildren and their fishing-poles, and get off easily one village down, with plans to return with perch for dinner. Trains are the images of what we understand ourselves to be, in relation to one another. Are we speeding our ways towards destinations, with either end of the shining track the only parts of import? Are we theoretically headed somewhere, senses open to whatever may arise at any moment? I had a dream once: a bus, crowded, with everyone on board, and my abbot as the driver. No question but to board. Of course! Here we all are. A bus in Tibet, groaning up an icy, muddy pass. We stop to mend one of the endlessly-patched front tires. People scatter to spread their contributions to the dung piles of the road to Golmud. We start up again. but where's the small grey man, with his limp? In the thin air, no one knows. Under a burlap bag? Gone? Turned back to a goat? The bus rumbles off. Left by the train, Left by the bus. It seems like the end of the world, and maybe it could be. Standing on some Siberian platform paying an old woman for steamed potatoes with dill, my ear is tuned to the engine, listening for the slightest change. That rolling village is my home that keeps moving. O preserve me from the home that stays still! Leaving the train means: leaving an order with its own logic and structures, its samovar at the end of the carriage, its gritty shitter, its PECTOPAH, devoid of food by day five, but still a good place for mint tea with lots of sugar, and real wooden tables with silver-caged glasses of the last five hundred miles' wildflowers. Leaving the train means agreeing to stop moving, and going into the early morning of some new town. Hello, new town! What's breakfast like, around here? Is there a place for some unusually sweaty, tall foreigner to park her bag? Sometimes - only rarely in the configuration I'm currently sporting - showing up off the train means ominous western music and the cast shadows of suspicion everywhere. Not paranoid, just genuinely weird. The local syphilitic madman as a retinue. The local laws against foreigners staying in hotels as an albatross. The question of when getting off the train stops being life-affirming curiosity, and becomes a really stupid plan. I go eat by myself, and people gather to watch me lift the rice and green vegetables to my mouth. I leave, but not by myself, saying the madman and the empty streets are nothing I wish to face alone. The cook grudgingly sends his boy to walk me home. When I got on the train, the first thing I saw was that this was going to be home, and I was glad I'd packed good silk pyjamas and plenty of ramen. I saw: in this four-person car, I was sort of a bystander to a long seduction by cherry preserves. The quiet bearded scientist, and the blonde lady whose traveling pantry included far more toothsome offerings than ramen. The first thing I saw was that this muscleman, his girlfriend, and their tiny white dog were very good company to have on a night train recently repatriated from Afghanistan, with anti-rock shutters on all the windows, and thugs wandering the corridors, thumping all the doors to see where they might be able to get in. Mr. Tattoos promised to tell me when we reached my stop at 4AM, and he was as good as his word, of course. The first thing I saw was that there was no way in hell we were making Newark in time to catch our planes to Switzerland. So much snow the windows were veiled, and the meld eked its way through the roof to bounce off the seat in front of mine. Snow slowing the tracks, snow sealing the whole East Coast in a coat fitting the season perfectly, barring all passage out. I finally made it across the ocean the next day, only to land in the embrace of another storm. Hundreds of cots laid out in rows along the smooth floors of Schiphol Airport, saying, This season itself is a train. Why struggle so much to get off? The sea, the sea, the always unpredictable, beautiful sea. Floating feet-up with my friend Stephanie, in the Mediterranean, age 14. We have just learned that the French title for Jaws is Les Dents de la Mer (Teeth of the Sea), and so we are being Feet of the Sea - Les Pieds de la Mer. We are grinning from ear to ear in that photograph, French sun off tan skin, off American braces, off the future none of us can see. The sea, the sea. Stephanie will have her braces off. We will swim again together, in Florida and in North Carolina, but we do not swim again as Leviathan until the day many years later, in Tennessee, when I follow my nose in painting, and find a green sea, a nine-story pagoda, a school of red fish, a teapot floating with myself as its finial, and a tiger blowing clouds in the sky. I know this is a story, and I know I am not the one to write it. So I call Stephanie, already several years into her brain cancer diagnosis, to ask whether she'd like to write some stories for some weird paintings that have started showing up. Sure, she says, but you aren't allowed to see the story while I write it. The deal will be: you make the paintings, and send them to me in groups of six. We agree there will be twenty-four paintings. We agree I will not know. We agree the sea is at the bottom of this, and we are floating in it. I dream I am on a small boat, with a guide, on the sea. The dream has a voice-over, telling some official story of the sea that I know to be untrue. What I know to be true is: underneath the sea, there's a nine-story pagoda full of treasure that belongs to me. As long as I do not take the dare of diving under the surface to claim it, thieves will plunder it. It is my choice, my birthright either to claim or to squander. A few weeks ago, I see this pagoda in San Francisco, in the tea garden, glowing red from between cypress trunks. It's not underwater anymore. I've claimed it. So Stephanie (aka JS van Buskirk) writes the story of Unless and Until, the story of traveling and forgetting. Two creatures inclined to do not-much return home from a journey they cannot remember. Where were they? What happened? One day, an old, battered trunk arrives at their cottage, full of paintings and odd objects. It is like the pearlized purple suitcase I bought from the Narcotics Anonymous thrift store in Atlanta. It has stickers from the Sands and from Cairo. Who knows where it's been? Who knows where we come from? Unless and Until slowly piece together their journey. Unless falls ill, and goes to the bottom of the sea, where they meet a whale - a fever-whale, a loss-of-voice whale, a whale of dying. The whale is the tumor growing in Stephanie's head. The whale is the suitcase we've each inherited from numberless befores, full of stories, including the one that spells our endings. I remember that painting. It's dark indigo, with glowing cobalt lines, with stalactites and stalagmites, with time itself, and with the spotted whale-shark Atlanta was arrogant enough to bring to its aquarium. Here, O Citizens, is Leviathan! Marvel at our powers! Leviathan promptly died. Or died slowly, which in this case is worse. Anyway, the whale is there in the painting. It's there in Stephanie's lyrics for Unless' song of illness and love, a song she herself would soon be singing to her husband, as the tumor leviathanized itself within her head. O whale! O sea! The night I lost my voice I lay in bed and felt with each swallow there was a double-edged knife in my throat. It was more pain and different than the usual sore throat. It was the sea and I was floating in it, head up. La Gorge de la Mer. I rose, took ibuprofen, drank tea, and settled in to read, as I seldom do anymore, recklessly into the night. A blind girl and her appointments with the sea. An enormous war. A boy listening for the whale-song of radio transmissions across the steppe. I read and read, and the knife slipped away, leaving behind silence. Today I can make a sound like a bagpipe, if I try very hard. Yesterday, my friend Ewa made me laugh so hard I found a squeak left over in one corner of my breath. It will come back. I whisper my way through a dinner party and realize the advantage of closeness with my host. Full-voice, I don't know quite how to approach him. In whispers, I find he tells me things that come from deeper in the ocean. Things not to be declared out loud. He is solicitous. I sip a hot toddy by the fire and find everyone in the room spontaneously lovable. Many things, under the sea. So, what did I find in that pagoda? The body was there, my body, with a knife in its throat sometimes, but also with the fullness of dance and the steady ballast of its solid frame. I found a willingness to see even what's uncomfortable to see: how the arrogant young philosopher brings wrinkles of pain to my friend's face, and how, in turn, his brashness is a symptom of feeling no one will listen if he talks any less brashly. The pagoda has mediocrity in it, and its opposites. Secretly, it's stupid to talk about what's inside the pagoda as though that were any different from what's inside this room:

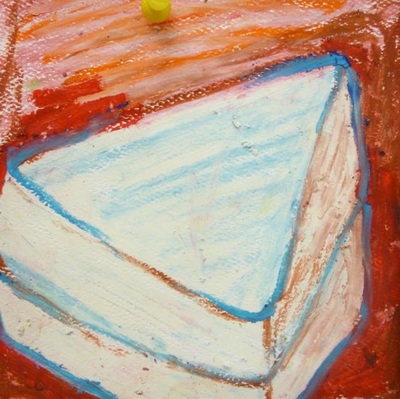

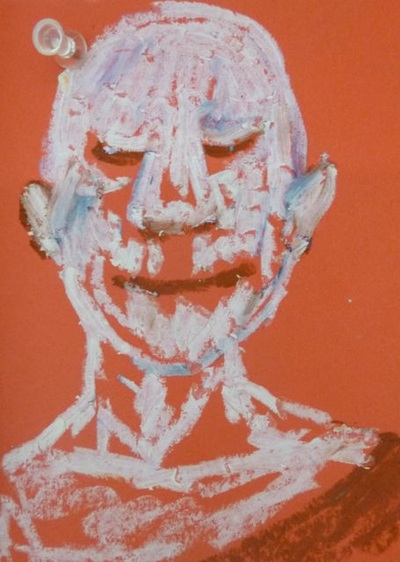

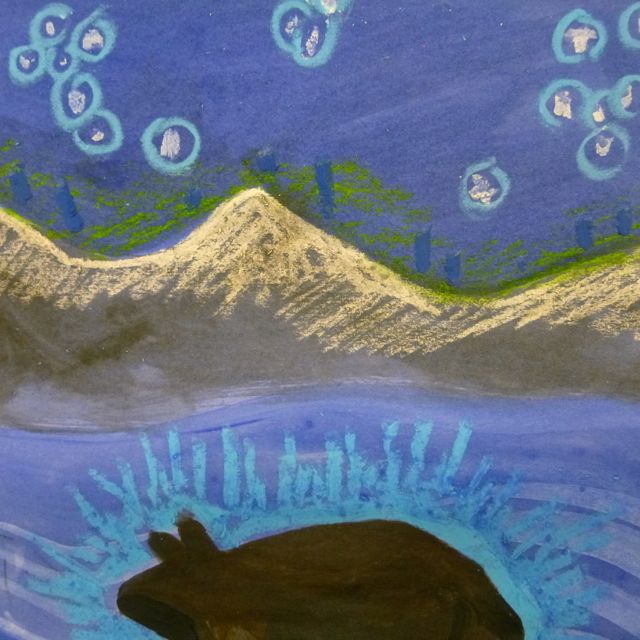

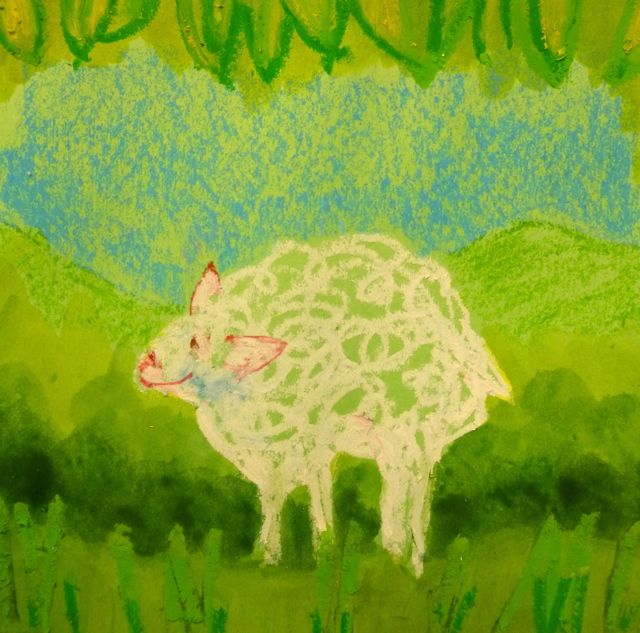

Arms sore in a living way. Nose moist in a living way. This writing writes itself, with permission to do so. This breath breathes itself, better with permission than without. These pen-strokes in concert. This sense of time unspooling deep within the timeless sea. Give me one wild word. Give me thousands. The end is the hardest part. One momentum has spun itself down, and another hasn't shown itself yet. The North. The pause between things. The whale blinks her eye and the pagoda's so deep inside every bit of experience, it makes no sense anymore to say thief or not-thief. Fishes flit in the grey mud Jacques Cousteau showed me as a girl. There are Frenchmen and Frenchwomen down there, Facebookers disputing the correct forms of grief. There are suicide bombers in their vests, and in their grisly post-vest messes. There are train whistles, and all the voices that ever whispered, sang, or questioned. And of course there's the small golden statue of Athena, nestled in the muck, ever-bright, waiting for the thief who will at last bring her back to the surface. She's there saying: Give me one wild word, or dissolve me forever in this sea. * Give me one wild word is a prayer I first heard from Terry Tempest Williams. Last weekend, I taught a third round of my Meditation and Art two-day workshops at AVA. Each time is slightly different, with the embodied Five Directions practice as a constant guiding structure. People who turn up for something like this are pretty self-selecting: you have to be interested in contemplative practice; you have to be interested in art-making; you have to be willing to dedicate a whole weekend to exploration, without the built-in payoff of CEU's, a famous teacher, or any established tradition. Just: pack your cushion & mat & lunch, and come on down. I could not have asked for a more marvelous group of participants, nor a better venue than AVA's sunlit South Studio. For me, guiding people through the cycle of the Five Directions, finding their own imagery and connections, their own challenges and griefs, their own wholeness and wisdom, is incredibly rewarding work. People know so much, and as soon as they feel there is a genuine invitation and safe space to reveal what they know, they open gladly into revealed presence. That might sound pollyanna, but I've seen it happen again and again. I'm going to post a few images of my own work from the weekend, describing the arc of the practice in a few images… PART 1: Offerings What have you recently enjoyed in eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind? Bring these to your attention, and offer them in gratitude to What Is, as you prepare to enter into the sacred space of contemplation, inquiry, and embodied expression. Part 2: Guardians Who within yourself guards the boundary of a safe & sacred space? These guardians could be bright, wrathful, or both. Part 3: Teachers and Lineage Who are your teachers? Who has shown you something of your true potential as a human being in this life? What are your lineages? Part 4: The Five Directions Part 5: Bringing the Mandala into Three Dimensions Working with the tactile qualities of clay, go into the directions, making a small devotional sculpture for each one. Let yourself be surprised by what your hands want to make. Let yourself see their particular qualities and their unity. So, those are the bones of the two-day Five Directions workshop, plus discussion time for each person to present her work, and periods of sitting and laying-down meditation interspersed. I offer thanks to all my teachers, and my students. Thank you for the chance to practice. Thank you for the chance to teach.

Yesterday night, my darlin' surprised me with a trip to the far north of Vermont, to see Mavis Staples. That's right: Mavis. In the Northeast Kingdom. None of the musicians could quite believe it, either. Joan Osborne, opening the concert, asked, Now, how do you say it? St. JohnsBERRY? or St. JOHNSbury? The crowd tried answering Lyndon Center, but no dice. And Mavis herself was like, It's good to be up here in… I was about to say Lyndon Johnson, y'all! Wherever we are, we're glad to see you! That doesn't happen on tour in Memphis. Still, a bunch of people up here in the far reaches of the Northlands banded together, raised some money, asked for stiff ticket prices, and bam! There's Mavis, in a golden tour bus, coming to sing to us.

You can see in this performance of Why Am I Treated So Bad from a couple of years ago what it's like now when Mavis sings. She's got pains in her knee, in her lungs & her feet. It's hard, because Mavis is not going to settle for fluting out some little song. She's connected to a whole enormous universe of voice, requiring every ounce of her strength. Her performance has a quality of awkward miracle amidst struggle. A huff on the inhaler, then another. A dropped lyric line and a grimace of disappointment. The band rallies around Mavis, she rallies within herself, and then she's got the whole power of Will the Circle Be Unbroken moving through her solid old body, for herself as for us all .

Seeing Mavis sing through and into suffering, I'm reminded sideways of the opioid drug epidemic & its ravages on some segments of the population. One of the things I've learned from offering mindfulness practices at monthly shared appointments for fibromyalgia patients is that opioid pain medications can permanently interfere with the body's ability to process pain. So: you had some pain you felt you shouldn't have, you took oxycodone for a while to suppress that pain, and now you have a body whose ability to feel anything other than pain is seriously compromised. That is, to put it mildly, very bad news. Mavis' prescription for moaning in Why Am I Treated So Bad offers a different possibility. You've got pain? Moan about it, and the Devil can't hear what you're saying. Of course you've got pain. Everyone has pain. That's what connects us, and gives us the courage to appear before one another, scarred and ragged, whole and brave. Stepping onto a Southwest plane requires keeping my ears pricked for what is really happening. Don't be swept away. Something amazing is just right here. Listen. There's a place for you. The way the airline structures boarding means that people who

We were just waiting for someone nice to sit with us, say the two smiling ladies I join in the third row. Of course, everybody nice. You smart, says the lady to my left, I been sitting here thinking there's room in that bin, and you just figured it out. Mm-hm. I introduce myself, and discover that both my neighbors are on their way from San Francisco to the 108th Church of God in Christ Convocation in St. Louis. Cool! I ask about the conference, and discover that these women have just met, which is pretty much what always happens to my neighbor on the right, when she takes the chance of traveling on her own. I tell my children I always meet other people on their way to the meeting, so they don't have to worry. My neighbor tells me anywhere between 40,000 and 60,000 people attend the meeting each year, so her confidence in finding fellow travelers is backed up by probability, and I can tell it's also grounded in the resilience of faith. I read for a long time, over the arid plains, and then towards the end of the trip, my neighbor to the right & I start talking again. She mentions her family: Mother to eight, Grandmother to 34, Great-grandmother to 38, and Great-Great Grandmother to 1, with another on the way. Meanwhile, this lady looks as though she could be in her sixties. Ma'am, may I ask how old you are? You certainly may, child. I turned eighty this year. Holy smiling matriarchs! I tell can see how proud and happy her family makes her. Do you have any kids? she asks. No, I tell her, starting about eight years old, I started telling people I never wanted to have kids, so I feel blessed to have gotten what I wanted. My husband and I are both happy this way - we love each other, our work, our friends and family, and our dog. That's good, then, she says kindly. We're all so different, and it's good to appreciate what you have. I pause to savor this acceptance between us: two very different women, respecting one another just as we are. It feels like sunshine. It feels like darshan. It feels like coming home.

I had a dog once, she says. Big ol' German Shepherd. I called him Bunny. Bunny Seymour. He was a really good dog. Used to be my peoples, I mean Black peoples, we didn't have dogs, but now everybody love dogs. Anyway, my daughter's baby started coming during a big storm - this was in L.A- and when the truck came to take her to the hospital, Bunny jumped up in the back with her and wouldn't get out. He thought they was taking her away, and he wanted to go with her. Lord! My son had to get up there, and get him out. Bunny was mad! He wanted to go with my daughter, wherever they were taking her. I tell Esther Seymour we have a dog we call Bunny, too, even though my Mom thinks it's a pretty silly name for a big black dog. Yes! she laughs. That's true. As we land, I ask if there's anything in the overhead bin I can help get down, before the wheelchair comes for Esther. Oh, yes, she says, my hat box. Your hat box? I waggle my eyebrows. Tell me about your hat! Do you get to wear beautiful hats at the meeting? Esther tells me about the Code of Hats - which colors for which days, to honor which sections of the {seemingly very male} church leadership. Glimpsing a world in which having a lot of hats is filed demurely under the guise of devotion to holy gentlemen, I ask Esther what she has with her on this trip. Oh, it's a little black one, with a real pretty flower that comes down on my cheek. Just looking at the gesture my neighbor makes in describing it, I see how elegant the hat must be, perched over her shining face, and how satisfying, to have lived eighty years, to have left rural Alabama as a child, to have cleaned houses and raised children, to have started a business and succeeded, and to be here, on this adventure in the sky, flying across the country to celebrate the great Heart at the heart of it all. As I lift down the big, heavy round box, expecting only the weight of a little chapeau, there must be a question in my eyes, because Esther twinkles, Oh and my mink coat. Esther Seymour, mother of Bunny Seymour and of multitudes, I think I love you. |

AuthorJulie Püttgen is an artist, expressive arts therapist, and meditation teacher. Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed