|

Left of center, off of the strip. That’s part of a Suzanne Vega song I both like and don’t like. Haunting, melodic, irritatingly inclusive in it’s depressive’s view of the world. I recognize myself and I don’t want to.

If you want me you can find me left of center off of the strip. That’s the thing about pop songs. That’s the thing about anything so here we’re me and self-confirming. Here’s the way the world is, it says. You are just like me, and we are like this. Yesterday I was remembering a protest sign I saw laying on the pavement at occupy Wall Street, so I googled the text and found that “the heart wants what it wants” is, in addition to a rainbow-background letterpress sign, and deeply gross thing Woody Allen said, a song and video by Selena Gomez. The song is about being in a terrible relationship, knowing it’s time to get out, and yet, the heart wants what it wants. I listened and watched the whole way through, and then read a bunch of comments from young women, saying how much it meant to them to recognize themselves in the lyrics. Is it then a way to excuse sticking around for more abuse? Is it a relief to know someone else is also sticking around to be abused? Not all pop songs have this effect. If I’d been first exposed to Suzanne Vega at a non-depressive, non-loner time in my life, it wouldn’t have gotten under my skin and stuck around the way it has, like HPV or chickenpox, forever a part of the ecosystem, whether dormant, or not. Left of center. Sinistra. In so many languages, the left carries the connotation of wrong, outside, minority, dark; while the right carries law, light and truth. This only becomes a problem when we forget that we, all of us, carry both halves. As foolish to identify with the right, as with the left. How are you going to walk without both feet supporting you? I will start a national Republicans Left Foot Appreciation Society. I will remind all Bernie supporters of the faithful service their right foot has rendered, all these years. This morning, scary news of the right foot: what if, in addition to being a buffoon and a narcissist, Donald Trump were also a tool for dark forces? Timothy tells me Russian intelligence hacked the DNC’s emails, and my first thought is, God! Why would anyone give a shit about that? But the answer comes right away: because Trump is Putin’s lapdog. I do not like conspiracy theory one bit, but sometimes it is true that a wound creates an entry point for other diseases to fester. My friend texts me that her little stepson and his friends held a séance, and now the dog won’t go near the kitchen, and the whole house feels wrong. Kids near puberty are favorite gateways for dark spirits, she says. I don’t know about that, but I do feel, sometimes, as though I am seeing possessed people. Laura Ingraham finishes whatever she’s been saying, turns to be huge image of Trump on the screen beside her, and Sieg Heils, before issuing Barbie waves and victory points to the crowd. I want to ask, What were you thinking? What moved through you? Did you feel it? Were you in that one moment a god? My friend’s house is possessed by whatever came through the Ouija board, Trump is possessed by whatever causes Putin to scuba-dive heroically for pre-planned treasure, and Laura Ingraham is possessed by whatever brings neo-Nazis to throw their salutes outside the RNC in Cleveland. Especially important, then, to be as conscious of one’s left foot as one’s right, to keep planting them both firmly on the ground, to keep one’s nose open to sniff out the real smell of things. I find no joy in opening new wounds or old. I find no pleasure in seeing the madness of the world, no confirmation there of virtue elsewhere. Just, pain. My bones ache, and so do others’. I take up sleeping on a pancake-flat futon, in hopes that it will cure my ills, and my bones still ache, until I decide to get up, write down the night’s flood of dreams, and remember: this is what it’s like. No séance, no charismatic leader, no specialized furniture is going to take away the facts of madness & ground, pain & the space to hold it. It’s hard, though. Hard not to be disappointed when waking groggy and sore. Hard not to want someone, something to fix it all and make it go away. Hard to remember that the only real solution is to receive whatever arises, without sticking to it like mad. Hard to take refuge elsewhere than in some imagined better time, or place, or self, or other. When was America great? When was the world great? How will they be great again, other than in the old way: by ceasing to demand that they be made in my own image. I know people who seem like they are being ground down right now, pulped by illness or by loss, by circumstances that don’t readily admit of feeling into the radiant intelligence of being. And yet, they’re mostly not turning to hate, fear, or resentment. Not left, not right, but center. Ground. Homing in on sanity like bare feet finding a sandy river bottom. I am sick to death of this election’s insubstantial ransoming of my attention and my allegiances. What if there are important questions we are not asking? What if we are focusing on all the wrong things? Well then, we shall have left-foot, right-footed ourselves straight into another grubby reality, always hoping for something better. The box is with Larissa.

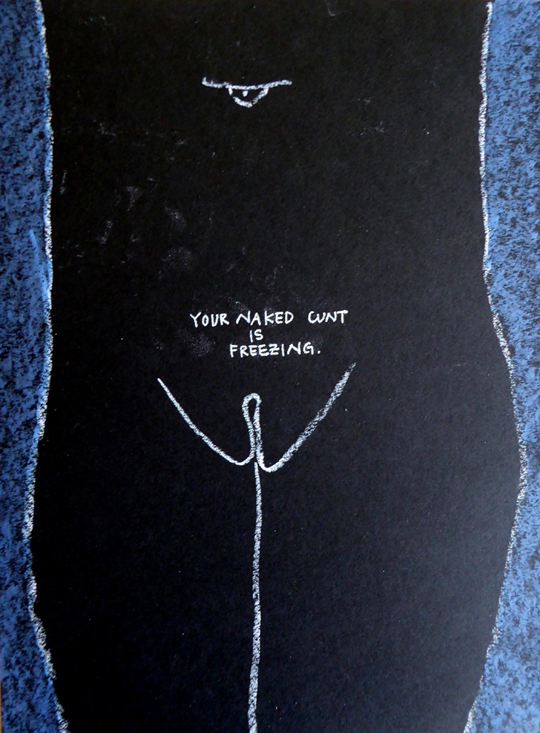

The box is with Larissa, and Larissa is with the hole in the ground outside her house. This morning, BQ and I are with one another, by the rivers, which this morning smell a bit eggier than usual. The birds are with one another, as, possibly, are the heavy machines rumbling this way and that. They call to one another: news of the universe. News of Cleveland: heavy machines are rumbling through neighborhoods where people have abandoned houses they can no longer afford, thanks to shitty loans and vanished jobs. In the short video, heavy machines break through the walls and ceilings of old houses, like vultures breaking skin. Old houses collapse into undifferentiated rubble, which is trucked elsewhere to be sorted by hand, by men whose building jobs left years ago. Now they are the carrion-sorters. They send broken bricks down the chute, send broken boards to be ground up for mulch, send metal to be foundered again into whatever. Beds, cars, new keys for old locks. The manager of the house-recycling plant says, “It makes you think.” It does. It makes you think. The leadup advertisement before the carrion-video on the New York Times site is from Microsoft, who, from the depths of their wisdom and generosity, have found a way to address billions of people’s deficit of… banking services. See? Before, banks were only available to some people, but Temeros (I think it’s actually called that) will fix this problem. Now, wherever there’s a man with a cell phone, there can be shitty loans for brown people! “Now,” [pan to Asian man hand-painting paper parasol] “people can start a business, and for the first time, hire people to work for them!” Thanks, guys with phones! We here with our exotic, flimsy umbrellas had not gotten that far in thousands of years! We were just, you know, painting umbrellas, with nowhere to go, and no one to help us. Whew! Banking sure saved the day. Just like it did in Cleveland. The box is with Larissa, and my mind is with all the bullshit, underhanded ways those in power congratulate themselves for making things in their own image, and squashing all the rest. The ways those in power magnify their pain, while remaining clueless to other forms of pain, particularly those they themselves are causing. Also in the news this morning: Law Enforcement Mourns Unprecedented Losses. Which, not to be callous, but, last time I checked, is eight. Compare that with, say, this year’s numbers of women killed by their partners, or prisoners killed in detention, or people killed in countries destabilized by our wars, and you really have to think that something is up. An unprecedented loss of eight, in a world roiling with catastrophe, smacks of unconsciousness about the pain of others. I know it is hard to remember to feel, especially when the box is with tribalism, nationalism, us, them, turf, right and wrong. Even asking the question, "How am I failing to feel the pain of others?” is hard. It’s important to know that. My wrist hurts from scrubbing like a madwoman yesterday, and from battling the huge sprawl of wild grape that has taken over the crowns of our improvised sumac hedge. My friend the botanist once described this section of the yard as our “invasive species collection,” and that is apt. I’m grateful to the sumac for shading us and screening us from the street, but I have no such feelings for the grapevines that twine and bind and crush everything in their path, and then produce unsatisfying, sour little pips for fruit. Not like scuppernong and muscadine in the South, which do all those aggressive things, but then also drop down sweet thick-skinned globes from the canopy. Scuppernong, in the right season, gives rise to Dionysian patches in the woods – places where the grapes have been crushed underfoot and fermented to forest wine. I do not feel the New Hampshire grapes’ suffering as I cut them down and shred them out of the sumac. I want them gone. I want them off. I make declarations like, "OK, you can have beyond this point, but no more. I am coming for you." The box is with Larissa, and the stench of the dump is with BQ and I. Sticky grapefruit, egg salad, gasoline. Sickly, I want to lay down and go to sleep in the grass. I rub my grape-slaying, fence-scrubbing wrist for support, and keep moving the pen. Under the table, please, just a little nap? The dogs throw themselves down – brumph! – and flop on the floor, their mouths hanging open, revealing gums like mussels, rubbery and plump. There’s a word in French – babines – and not in English. We have no words for dog-cheeks like shellfish, the box is with Larissa, and I want to lay down. The heavy machines keep rumbling. Yesterday, in meditation group, we talked about the possibility that our desires might be God’s–through-us. That what we want is actually what we are supposed to do. Does God want me to take a nap under the table? The train horn blast visibly startles both BQ and I. I guess not. OK, then. Awake. Writing. The train speeds up. What if the whole shaggy mess of life were about tempering one’s desires? Learning by indulging them, exploring them, and gradually, in this way, burning off what in them is not essential. Dangerous: who decides what is nonessential? Some dragon lady within? Some desiccated priest? No. Some ring of truth. Allyn from the Zen Center tells the story: the thing had been used at Dartmouth as a planter for years, and then sent off – too large! unfashionable! – for recycling. A guy at the physical plant noticed that if you hit the thing it rang for five minutes. Maybe it was worth paying attention to? It rang true. The inscription no one had noticed said it had been cast 250 years ago, as a bell for a temple in Japan. Someone remembered it had been brought to this country by Mr. Ripley’s Believe It or Not, and then given to his somewhat inattentive Alma Mater. It’s like that for us, believe it or not. We discard, say, dancing, as too large! unfashionable! And just when it’s on the brink of being recycled into productivity-pellets, some worker underground strikes it, and it rings for five minutes. That’s a desire that has stood the test of time. That’s one to let out of the box, to keep close, to allow to grow and shift as it will. The nap under the table, by comparison, might as well get melted down, so we can find out what comes up next time. Hey presto! A little gentle rub of the shoulders, a remembered story, a glimmer of recognition in the murky water. Testing and proofing desires is scary, takes time, and precludes a lot of glamor-selfies and other leakages of Little Me into the arena where the action is unfolding. Great stinking piles of rubble must be made and gone through. I myself must become the carrion worker and the carrion, the ruined house and the clean land reorganizing itself into wild pinks and sumac, woodchucks and raspberries, a meadow with a gnarled wood beside it. In my grandmother’s house, no one has a Brazilian wax. In fact, no one’s ever even considered the possibility of such a thing. Other forms of lady-oppression: confinement to home, Catholic wifehood, no problem. But the systematic removal of one’s pubic and anal hairs, over and over, at the expensive hands of strangers? Try to be serious. In my grandmother’s house there was a small, dark room on the third floor, where servant women lived. Shall we say servicewomen? I like the sound of that better. I can remember two: Tita, a beautiful, sturdy Spanish woman, whose fiancé had been killed by Franco, and who came to devote herself to my mother’s family over decades, first raising my mother her brother (the youngest of five children), and then the children of Toty, my oldest aunt. Tita could look magnificently stern, enough to corral a half-dozen excited little cousins into their pyjamas, but we all knew she was kind, and we respected her. I was too young by far to know the word duende, but I had a felt sense of it, and I knew Tita carried deep roots of sadness in her, and of love. Because I did not feel entirely at ease in my family, I think I respected her strangerhood among us, the graceful way she had of taking care, making soup, pinning laundry to the line beyond the lavender rock garden, and still being a citizen of her own world. Tita eventually retired to Spain, to rejoin her larger family, and my cousin Mathilde, whom I considered a pest, got to spend parts of her summers with her. I envied her those excursions to the land of Tita’s citizenship, but I knew Tita had loved her in some sense back to life – this premature, tetchy baby she’d tended in lieu of the children she might have borne herself. I don’t think I ever went into Tita’s room when it was hers. It was private. I had no passport and no claim to that space then, or later, when it became Jeanine’s room. Jeanine succeeded Tita, and was a very different kind of person – a Jura village girl from Blye, not far from my grandmother’s house. Jeanine had afflictions– epilepsy, maybe Down syndrome, whiskers from her chin, and a clubfoot. It was not easy being Jeanine, and I think maybe this is why my grandparents hired her – to get her out of her poor village, to let her rest in simple paid work, to remove bullying or abuse from her life. I could not forgive Jeanine for not being Tita, for not being glamorous, for being pathetic. So that’s one idea. But I also remember being in the narrow kitchen in the south of France together. Both of us, and my grandmother, wrapped in aprons stirring and peeling and chopping. Little, I was doing few of these things. Instead, I was playing with the worn brass weights of the old market scale, or looking at the row of magnificent objects resting on the shelf above the radiator behind the kitchen door. An iron kilo weight. A woven rush trivet. Jeanine, too, had a citizenship that set her apart. Unlike Tita’s, it wasn’t one I wanted, but it did serve to remind me of a world outside my family’s insistence that theirs was the only one. Jeanine left my grandparents’ house and went back to her village. Then, I remember going to her wedding in the church in Blye – an old thick-walled chapel whose Rococo nonsense-angels had recently been restored. The whole thing – ugly pink, green, and turquoise heaven on sober walls; awkward bride and groom; heat and stillness of a late August day – fed into the angst-engine I stoked so faithfully in those days. Today, I might have noticed the good faith of the assembled, the acknowledgment of Jeanine’s determination to be happy, the efforts that had been brought to this mostly-unused, remote building, keeping it from ruin for another set of decades. After my grandmother died, I flew to Switzerland to be with my parents, and to help my mother with some of the house-clearing. The small room on the third floor that had been Tita’s and Jeanine’s, and long before them, Nannane’s, had, in the intervening years, been turned into a kind of storeroom for objects acquired in various family deaths and rearrangements. The radiator wore a Persian carpet and a fox skin. It was the shaman presiding over the framed grid of pinned insects on the bed, the cloudy-mirrored washstand, the tall armoire jostling for space. The whole room had the intelligence of a material hive-mind. It was humming with plans, none of which included humans. Alive, alien, coherent in its juxtapositions and its confidence that furniture has many other things to do besides: be sat on, be walked on, reflect back morning whiskers. I suppose each era has its own ration of suffering, and so it shouldn’t be surprising that here and now, 62% of American women are apparently choosing to have their genitals “groomed.” By and large, the visible signs of oppression are subtler than they’ve been, so we turn to intimate violence. We turn to taming our bodies, making them “clean,” and “healthy.” We become the rats in overcrowded cages who chew their fur, or one another’s fur, forgetting in that denatured space that we are all part of a great and radiant intelligence, whose design most certainly encompasses our furs, and all the furs of others. We go from bikini wax to Brazilian wax to Hollywood wax, meaning apparently, Everything Must Go. Who says? Pubic hair growing back itches like Satan in your pants. And pubic hair being pulled out hurts in a distinctly unhealthy way. I personally opt for the Wu Wei wax, which means leave everything be. Wear swim trunks to just above the knee, within which all kinds of exuberance can unfold un-fucked-with. I declare my lady parts to be, among other things, like the room on the third floor in my grandmother’s house. They are off-limits to the pornification of this culture. They have a citizenship all their own, which is the citizenship of the body on its own terms, not to be used, but to hum with knowledge. I think about these things, feeling into my own body aging, and seeing the bodies of my friends, going decade into decade. There is a hawk inside me, circling, watching coldly for signs of weakness. That hawk is a hawk many of us fear, and she is not born of the body’s own logic. She’s born of the culture’s shaming and suggesting, knowing archly that surely THAT won’t do. So, okay: I cut the cord to TV and media and magazines, and the poison takes awhile to purge. Inside me, there’s also a growing awareness of the body on her own terms – the body that knows – of course! – how to sit and how to rest, how far to walk, and how to let music come coursing through every joint, and dance. To this knowing, the meanness of adolescence is mosquitoes, gnats, thorns – annoying, but then, what do you expect? To walk this world of gentle breezes and avocado salads is also to walk this world of cruelty and condescension. I am still at home.

Really, my grandmother’s house is the temple of this imagination, declaring from the third floor sewing room, Dieu Seul. There is only God. God in the addictions that bring us to harm, and God in the courage or simple groundedness that brings us out of addiction. God in those whose callousness brings us to see our own, and to dismantle it. At the end of meditation group yesterday, someone says, “did you see the pubic hair dress?” as if that were thing on the order of Lady Liberty, which perhaps it is, after all. Gathering together what’s been rejected, excised, ripped out. I still think the body knows best where her own parts should live, and how they should grow, but perhaps a gown of pubic rosettes is the homeopathic first step. In my grandmother’s house, everything finds its place, and loses it, and settles into its own gravity to find home again. The fox fur drapes furrily over the mouse-nibbled carpet, and in their commingling, something new will emerge from resting and rotting rooms. Are we there yet? I mean, is it time yet to stop waiting for the right time to be here, and just get on with living? The birds gave up years ago. The rivers gave up years ago. The trains – well, no one pays attention to the trains, so who knows what they’re feeling about anything, and whether, Amtrak after Amtrak, those empty dinosaurs think about anything at all? From Tuckerbox, watching the Nor'easter rumble in, brontosaurusly. There is no one inside. It slides by. Are we there yet? The river says, What? Because to a river neither there nor yet make any sense. We it can get behind. We, the otters, and their fish. We, the homeless seeking refuge along shady banks, we the children swimming and the teenagers flinging themselves off trestle bridges into mostly deep-enough pools. We is fine, and makes sense. We, made of rain and springwater. We, filtered through sewer systems and shitty septic tanks. We, peed by labradoodles and old men, squirrels and mayflies. We. Are we there yet? There’s a quality of being, present in the body at all times, that lets this question free fall down through the middle of the earth, and come out the other side, free falling up into the sky. It’s there in your elbows, and it’s there in the warmth of your throat, sipping sweet milky tea. It’s there in your feet on the ground, in your cranky back, in the picnic table, and in the sticky soda splotches interspersed with sap rising through the paint. There is no place it’s not, which is precisely why me-mind doesn’t want to hear about it. If all beings then, why the fuck do we think it’s okay to raise pigs and cows in boxes? If all beings then, what kind of a story is schools funded by property tax? If all beings then, tell me again about national borders and their critical importance to protecting the safety and economic interests of our good citizens? Are we there yet? I look at a photograph of Hillary Clinton, and see a vulnerable older person. Not an idea, not a voice that causes me to run to the suspended television in the airport, hoping by some chance They have left some discernible off-switch accessible. A person, with There Yet, There Already and Always There, in her bones, her heart, her stoic and cunning mind. Are we there yet? We stumble barefoot through the woods, hoping to find a way down to Lake Sunapee, so that we can swim out of our wedding clothes. We never find a way, but we do find release in leaving the lawn, the great house, and the somehow disappointing buffet behind us, and padding along where red squirrels and porcupines exude their atmosphere of purposefully aimless wandering. The oaks can’t even move, for fuck’s sake! How are they going to care about a question like Are we there yet? Yes, we're here, they say, rooted more and more deeply, exactly where we are. The squirrel is rummaging in dry knotweed leaves for the sandwich she knows she left there just last night. The freight train thrums across the river, squealing metal on metal. A farty motorcycle. The leaves’ shadows dancing on the notebook page. There is, in this writing, the quality of time passing consciously, and there is also the effort not to slip back into forty-minute mind. I am looking for the squirrel-sandwich urgency, the sense of it’s right here somewhere! But not the kind of impatience that dismisses being late, or being early, or fiddling around with words in a composition book. Do they even still make those anymore? Are we there yet? When I was eight years old, my parents drove from Fresno to Atlanta, stopping off in Houston to drop my brother and I off at the airport, so we could fly to Paris, and meet my grandfather. By the time we got there, the workers in France had been on strike for so long that garbage had gathered waist-high in the Barbarella space-tubes that connected the different parts of the concourse. Anyway, I lay in the back of the caramel-colored Chevy Malibu station wagon, reading and humming songs to the engine, until, in the middle of Death Valley, I barfed everywhere. Cool. Now I can imagine what that was like, for my parents: We’re in Death Valley! We don’t have much water, and yet, there’s no way we’re driving around breathing in ham-sandwich puke until we hit Phoenix. Are we there yet?

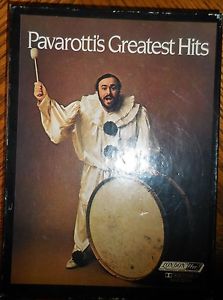

After that, I couldn’t read in the car anymore, which left My Boat Comes to You, Filled with A though Z Assorted Goods, played in the round as a family. My boat comes to you filled with Electric Tape! It left sleeping, and singing songs to the engine with my head up, so I could look out the window, which wasn’t nearly as good, because then the engine could hardly hear me. I think this was too early for cassette tapes, so we didn’t even have Kenny Rogers or Pavarotti’s Greatest Hits to smooth us over the desert. We were not there yet. |

AuthorJulie Püttgen is an artist, expressive arts therapist, and meditation teacher. Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed