|

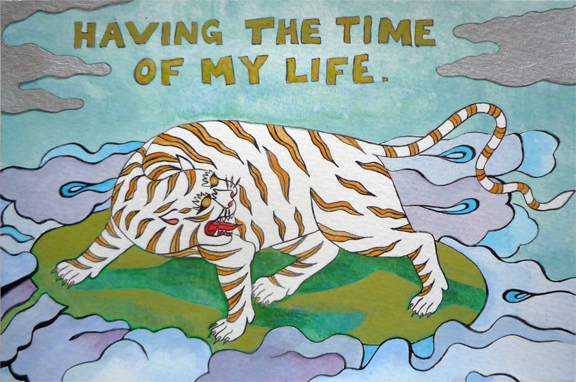

The monsoon happens every year, so you'd think plans would be made to deal with it, but, no. Actually, that is a very in America, death is considered a fiasco kind of a thing for me to say. Monsoon, like death, like dog-bite, is not a thing that is subject to plans being made. Monsoon happens, and with it, the power goes out, the roads go out, and half of Shimla town's main street slides a little bit further downhill. Also, leopards get so soggy that they attempt to take shelter in the school cafeteria, which does not work out well for anyone. Leopards get shot, without even a maw-full of chana masala to make their efforts worthwhile. I had read seemingly endless written accounts of the monsoon before I ever encountered it for myself. There were anecdotes in the Raj Quartet, of course, and maybe also in A Passage to India, which I don't remember very well. Best of all these is Alexander Frater's Chasing the Monsoon, one of the maddest travel books I have ever encountered. The basic idea is: a highly-strung, eccentric British journalist follows the enormous rain-front of the monsoon from where it originates at the nose-tip of India poking into the ocean at Trivandrum, all the way up to Meghalaya, in the far eastern Himalayan ovary of the subcontinent. Everywhere he goes, it looks like this: the world is absolutely parched. No one's seen rain for months, and life is miserable with dust, flies, and heat. Then, a great wall of cloud rolls in from the south, preceded by a wind laden with leaf-shreds and delicious wet smells. The rain breaks. The streets flood to waist height, full of sewage, dust, and anything not securely attached to anything else, which in India is basically everything. The power goes out. People leap off of balconies into the sludgy flow, and frolic. All work ceases. The rain falls for weeks. Frater gets more and more worked up as he sees the monsoon break over and over. It's possible no one is actually supposed to live this madness day in and day out, kind of like going to a single concert is exhilarating, but if you follow the band around on tour, you are likely to wind up with troubles of the kinds nomads often find, in a sedentary world. When he winds up in Meghalaya, he has gone from the place where all rain is born, to the place where all rain dies. It's the wettest place on earth - hundreds and hundreds of inches per year - all rain stopping there, unable to reach over the mass of the Himalayas. I've not been to Meghalaya myself, but I have seen what happens when you cross over from Central Tibet into Nepal. From the bone-dry plateau, with a few yaks munching thorns here and there, you descend to lush, orchidy forests, with monkeys jumping from tree to tree. Anyway, when I did finally meet the monsoon, it blew my mind. Growing up in Georgia, I had seen torrential rain, and the eerie green light of tornado-forming storms. I had seen flooding. But I had never seen whitecaps scudding downhill four times a day, for weeks. I had no idea it could even rain that much, let alone keep doing it day after day. I was living outside Dharamsala, studying with a Tibetan thangka painting master for a couple of months. The work was meticulous, and because the intense weather made the outside world feel inaccessible, I surrendered deeply into drawing and painting. Nowhere to go and nothing to do. We could only paint by daylight, since the electricity was both erratic and weak. So at night, after dinner, I would retire to my little stone room, and sit in the bay window, reading, or drawing in a looser way that could be managed by candlelight. It was amazing how much time I felt I had. The crummy PC drone sat in the corner of the room, neutralized as much by the lack of electricity as by the glacially-paced Himalayan dial-up connection that was the best it could ever offer, monsoon or no-monsoon. Everything opened up wide and dark, with old stories of flying siddhas and miraculous animals to keep me company. I dreamed wild dreams, with the mountains towering nearby, the leopards eating goats nearby, the whole unseen world breathing under steady downpour.

I saw something then of what it might have been to live in a world lit only by fire - the world of Georges de la Tour, of Caravaggio, and of everyone, really. It was spacious and quiet, and I had the excellent company of a series of novels bought and resold in Dharamsala's many scrappy used bookstores. My favorite was Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall. I had enough distance from the patterns of my own life to be able to see the patterner Thomas Cromwell in his life. I resonated with his understanding of people doing the things we somehow must do, as the rain must fall, and cascade in through the window of the unwisely built new dormitory next door. When I came home to steady power, while I wished for the vastness and quiet of that time, I had trouble re-finding it. By 21st Century American standards, I live a relatively distraction-free life: no TV, little phone, no radio, no kids. But, ah! The internet! Its combination of free-floating curiosity and illusory, infinitely extendable productivity does me in. The lights are bright, making space and things more concrete. There's the house to tend to, the dishes to wash, and the dogs to take on their nocturnal pee-wander. Still, sometimes, all that falls away, and my husband and I find ourselves giggling about the day, and all the things we can't control. Our new dog, who is growing into growly adolescence. My inability to reframe certain annoyances as passing weather. His ongoing last-minute dashes to pull together materials for the next day's classes. All of it a downpour, and all exactly right. The closest I come to those powerless monsoon-nights are the nights I spend on retreat. Nothing to do, nowhere to go, and the night opening vast and dark on all sides. |

AuthorJulie Püttgen is an artist, expressive arts therapist, and meditation teacher. Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed