|

Fairy dust. Dust bunnies. Dusty old tales of yore.

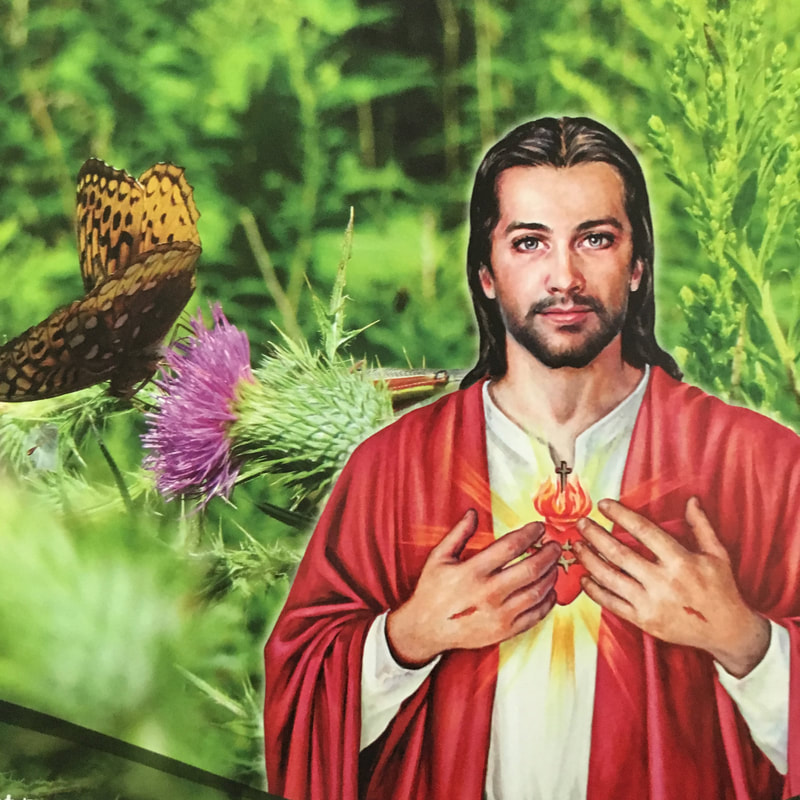

Dusty is the household life, a rubbish heap. Washing the dust from His feet. Washing the dust from Her eyes. Angel dust. How long it will take for this body to turn to dust? Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Taking handfuls of that young man’s ashes and throwing them into the brisk English air. All we are is dust in the wind. Snot, oil of the joints, undigested food, oil of the body, hair of the head, hair of the body, teeth, nails, skin, marrow, stardust, stardust, stardust. Anything I pick up in my studio tells me dust-stories about just how long it’s been since I last picked it up. Two weeks? A modest sprinkling. Two years? Elaborate dust-spires have formed, and the object is transitioning to a kind of dustful rest. I can sweep it off, but the truth is there: From dust you have arisen {paint-rag} and to dust you shall return. In the monastery, there was a formal way to request that whoever was assigned to give that evening’s Dharma talk surrender the goods: Brahmā cā loka tipati sahampati, Kat añjalī andivaraṁ ayājathā, Santīdha sattapara jakkha jātikā, Desatu dhammaṁ anukampimaṁ pajaṁ In English this is roughly, From the realm of the gods came the world-ruler Sahampati, requesting with joined palms that the Buddha teach the Dharma to those with but little dust in their eyes. No dust? Not a chance. But some beings, the request suggests, have not gone too long without shaking themselves of the terrible ideas that afflict most of us, most of the time. For me it varies day by day, how much dust I think I have in my eyes, how much is actually there. This morning I woke lazily, but cheerfully, ready to meet experience without ill will. OK, stove, let’s do this thing. OK, bread, I think there’s time. OK, dogs, let’s go skid around on some crusty snow. OK, book, I’m getting closer to having you figured out. Who knows, really, but the feeling is of less dust. Not because there’s no pain and everything is solved, but because there’s less resistance to what's there. More love for What Is means less dust? That seems plausible. Nadia Bolz-Weber, sort of a rock star in the Lutheran world, talks about the distance we tend to imagine between ourselves as we are, and ourselves as we should be: Dusty Mofo Me, and Dustless Me of the Future. She makes the obvious but elusive point that What Is is always in relationship with what we actually are. Of course. It’s not called What Is for nothing. But meanwhile, if we distract ourselves in relationship with what should be, we miss the opportunity to be loved. We fret about dust and forget innate wholeness. The way she describes all of this is moving and self-evident. Don’t imagine that God is waiting to love someone who will never exist. Don’t allow dust to disconnect you from the deep sources of your worth. When I was a student, the sculpture building at Yale was far removed from campus, a vaguely alarming post-industrial warren of dangerous equipment opening into cavernous spaces. My TA, let’s call him Matt, was a deeply devoted resident of this building. One day I came in for Sculpture I (a kind of study-abroad for painters like me), and someone had block-lettered MATT IS A DUSTY MOFO across the back wall of the studio, in what looked like drywall compound. It struck me with the force of love. Someone sculpture-loved Matt, just as he was. It’s stuck with me, and sometimes a voice that sounds a bit like JULIE IS A DUSTY MOFO rises up grinning from the ground of being to fill me with delight. Dust is funny: it can mean neglect and also acceptance. I reach behind the seat of our small red car and grasp a ball of dusty dog hair, dried leaves, and pine needles. Neglect plus acceptance. How likely is it, given fifteen free minutes, that I’ll deal with this, instead of making myself a cup of tea and reading something random online? Not very likely, until it is. I now know there’s a gas station nearby with free air and free vacuum. Someday, everything will come together, and that dust-wad will get sucked into wherever gas station detritus goes. Meanwhile, I’m not too worried. Holy, dusty places. Dusty, holy places. Some of my first exposure to both happened in central Tibet. There’s very little water, lots of places, and it’s cold, so laundry’s just not something people do a lot of. The wind whips mountain dust into tall, whirling devils, and all the colors outdoors are mediated by a fine coating of the world’s disintegration. Holy, dusty world. I remember going around with the bandanna tied over my nose, Annie Oakley style. I remember dust in my ears, in my eyes, my nose. The Himalayas thrust upward each year, while the winds sand them down to dust. Sometimes I can feel parts of myself being ground down and polished by those same winds. My ambitions and resentments soften; my mistakes feel less grave. This morning I accidentally squirted out way more of my expensive face cream from the tube than I needed, and the first thought to arise was, Let us celebrate the festival of roses! I smeared the fine-smelling stuff into my face, neck, chest, and hands. Life is too short to get testy about flailings like these. So what if the sheets are a bit dog-dusty? We all slept so sweetly last night, and this morning the sun has a better chance than usual of piercing through December gloom. I’m on the last page of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart Sexy Jesus Calendar that my nun friends gave me last year for Christmas. Instead of ordering another one, I think I’m going to collage my own this year, pasting the radiant heart of Jesus over sandhill cranes, polar bears, and urban parks. I’m going to put the Sexy Jesus back into nonprofit environmental conservation and birdwatching, as my reminder that all that is dusty is not lost, and all that is lost is not dusty. He will smile at me for another year, dustless, stainless, smiling, and secure. I’ll smile back, remembering JESUS IS A DUSTY MOFO who loves me just as I am. |

AuthorJulie Püttgen is an artist, expressive arts therapist, and meditation teacher. Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed