|

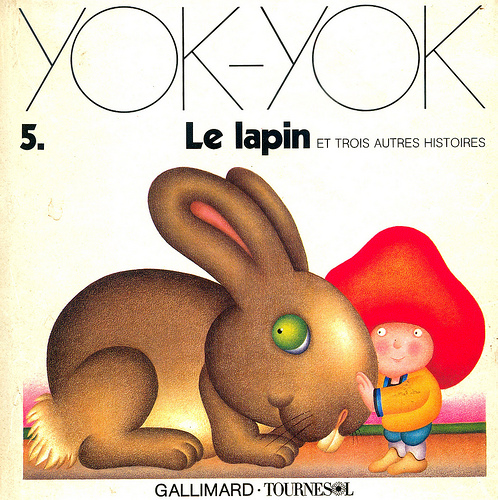

Once upon a time there was a child. Actually, there were two children, and between them, there was one tiny rubber duck, no bigger than the thumbnail of the hand that is holding the pen to write this story. Back then, it may have been half the size of a child’s finger. Anyway, it was called Duck-Duck, and it lived inside a small, clear plexiglas cube, which, in turn, was supposed to live on the shelf above the first child’s bed. But, being so irresistible, Duck-Duck had a way of wandering: amid the socks in the dresser, into the cozy underspace beneath the second child’s pillow, at large in the abyss of longing that can open up inside a childhood bedroom. Instead of a proper bedtime story, the children and their mother often engaged in ritual mourning for Duck-Duck, keening, searching the room, crying their pillowcases soggy, until sleep or duck-restitution ensued. I do not know how my mother endured so many repetitions of this drama. Maybe it only seems to me to have been some existentialist version of a long-running Broadway show. Maybe it was only four times, but it was enough. This morning, Elliot stopped cold in his prancing tracks, sniffing and twitching away from something in the grass that first looked to me like a big nugget of bark. Then I discerned a small sharp-beaked head, black eyes, trembling body. Elliot is mortally afraid of feathers, and so the fledgling was helped by the horror that tempered his curiosity. I pulled him away, and we went on. But on the way back, he rushed ahead, took the whole creature in his mouth, and crunched vigorously. Remembering past frail fledglings I have failed to save, I thought, Well, maybe this is a kind end – swift, definitive, in Elliott’s clean, warm mouth. He pranced on, feathers sticking out of his snout like the proverbial fox leaving the henhouse. He stopped, crunched some more, allowed a long thread of sinew to dangle to the ground, bloodily, ate it, and pranced on. I realized I had never seen a creature so quickly and completely consumed before. The fledgling’s disappearance was far more direct and incarnate than Duck-Duck’s erstwhile shadow-plays with Being and Nothingness. Trembling, the bird is taken into the dog’s mouth. Its body is rent, chewed, swallowed. Later, I pat this dog’s long ribs, and know that they are not only made of kibble and grass, but Bird also. I did not try to stop the dog. My back hurt so much this morning that a slow, canted walk was all that I could manage, and any significant attempts at dog-discipline felt beyond me. I hobbled along. Maybe I was hoping some even larger carnivore – a T Rex? – would come along and snap me up whole. No, not a T Rex. One cannot imagine their mouths as pleasant. A dragon? Maybe part of our problem, as humans, is that there is nothing Elliott-like around anymore to eat our trembling bird selves. I don’t want to be mauled by a grizzly, or a mountain lion. If anything: swallow me whole into your mouth, please. Maybe that is why there are so many dragons in bedtime stories. Maybe that is why people turn to bad marriages, religion, all-consuming work, or drugs and drink. Swallow me whole! This trembling out in the open on my own is too much to bear. We had a storybook called Moe Q McGlutch, You Smoke Too Much. It was about a nicotine-addicted dragon, who eventually smokes himself to death, much to the relief of all his creaturely castle-mates. I’m pretty sure someone besides my mom got this for us (she might not have dared), and it made my father’s smoking instantly very unpopular. We probably never liked it – smoking is stinky, after all, and my father would lurk moodily with his smokes in front of TV golf tournaments, when my brother and I would have liked to partake of the brightly-lit, muppetish gospel of hope, silliness, and learning. Anyway, his association with Moe was both foreboding and amusing to us. Eventually, my father quit smoking, and no one noticed, until one day my mom realized: no more ashtrays, no more Moe. The story retired around the same time, its work fulfilled. Other stories arose and retired: the ones in Swedish that my grandmother read me, the one about the elves living in the big beech tree, the Yok-Yok ones about the little boy in the giant red mushroom hat. Now they live again, at my parents house in Switzerland, at the bedsides of my brother’s two boys. When I go to visit my brother and his family in Baltimore, I tell my nephews new stories, gotten from the library by the armful. There is a whole series about some sociopathic bunnies with hyper-thyroidal eyes (not at all like Yok-yok's giant furry pal), wandering around glooping and pooping, laying the world to waste, while laughing at one another’s misfortunes. They are truly awful books, truly awful bunnies, but, for good little boys, I can see the appeal. For fifteen minutes at bedtime, mayhem comes to visit. Then the books are closed, the sheets are drawn up around little chins, and order is restored. It’s a very good deal.

The bedtime stories of immigrant families like mine are complex: the parents’ childhoods are far away, and paradoxically, so are the children’s. Where do they meet? Can the wolves of New World and Old agree on how to lurk, and in which woods? I think of the thousands of refugee households globally, in tents, abandoned resorts, rest stations, and Olympic stadiums. Is there space and support for stories, when everything’s gone missing? Or in some sense are the moments before sleep spent in some disordered ritual of searching for what might never be found? My back still hurts like hell, sitting at this wooden picnic table, notebooking away in the rising breeze of what may be this afternoon’s rain. Yesterday, dancing, my friend asked, have you been sending your back light? Have you been breathing space and love into there? No, but what beautiful stories. Try to remember. I do. In addition to the huge maw returning us to earth, there is a force of love that can open up, swallowing us while making us more whole. We’re always caught between the two: Eat me! Annihilate me! Restore me to myself! It is the second story – the one about being seen kindly in the midst of trembling – that knits the sundering world together. |

AuthorJulie Püttgen is an artist, expressive arts therapist, and meditation teacher. Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed