|

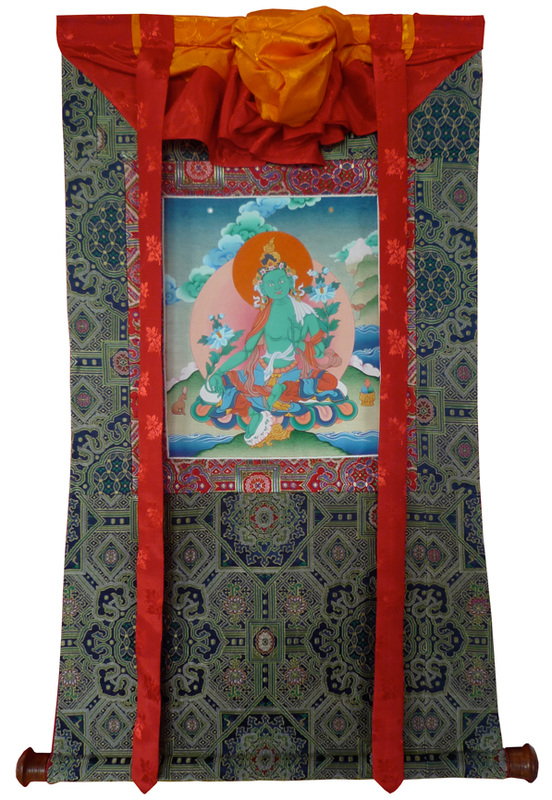

Waking up, stretching, having a good look around. Tara's still here, the green curtains drawn, the Bhutanese universe above me & the old Venetian mirror above the dresser, ghostly number 16, bowing lovers. Above the window, there's a painting I made while looking at a desk lamp, shining down into a pane of glass, on which rested several potatoes and onions, plus some oranges studded with cloves. This was my way, at 21, of saying, Everything orbits around the core of some central, bright intelligence. I spent a lot of time in that Gothic attic studio, with the lights out at night, burning candles, moving around the desk lamp, orbiting potatoes around a central core of longing to wake up. I am not even sure, back then, that I knew waking up was what I wanted to do. I thought I wanted to be a painter. I thought I wanted to be a photographer. Night after night, I was going into an empty art history classroom in the dark, photographing my shadow against the chalk crosses I drew on the blackboard by the light of an ancient slide projector. Dingloskeit. Thinglessness. I was becoming aware that what was interesting here was not Me becoming a painter, or a photographer, or a painter-photographer, but this longing to understand light and shadow, embodiment and emptiness, marks and potatoes, and the ways they could be made to play out scenarios of my longing to wake up.

Later, living in Hong Kong, I gave up the classroom & the studio, choosing the world instead, waking up to the saddle shape of Ma On Shan, in October days where all the smog blows away, and the mountain stands awake, wave after wave of long grass whipping up the wind to meet it. I still made photographs, but these were of the world as I found it & it found me. These photographs had altitude sickness in them. They had being kicked in the ass by an angry monk in them; homesickness and anger in them; wonder and curiosity in them. Moment by moment, in allowing myself to be a free citizen of a much larger world, I was waking up. Central Tibet had a kind of nerve-jangling rawness, everything turned up to barely-withstandable intensity. The sun fried the tops of my ears to blood-blisters. The air scoured my throat with smashed mountain-bits. There were bones everywhere, and just when things seemed nice and dim and colorfully soothing in some temple, I would notice that what was painted on the walls was flayed bodies, piles of guts, eyeballs winking from flaming gobs of brains. Tibet wanted me to wake up. Tibet was not letting me get away with blaming and aestheticizing, idealizing or distancing myself. I was going to be in this crappy jeep for days and days more, with no way to go to sleep, no escape from my travel companions, and no way to pretend that what I was encountering was not worth paying attention to. That summer of traveling continued in raw, unplanned, unmediated, yet merciful intensity. I arrived in Dharamsala just in time to book the last room in town with two strangers: an American yogini, and a British meditator. What did either of these things mean? Besides photographing my shadow in the dark, I had had little exposure to other people who might be stumbling their ways towards waking up. The yogini had a snake tattooed wrapping around her toes; the meditator seemed dissatisfied about a lot of things, but happy to have found a place to sleep. We all went to see the Dalai Lama the next day. First, we had to stand in line to have our passports registered with Tibetan security. Then, we - hundreds of us - stood around grumbling in the hot sun. Whoever heard of a bunch of international hippies standing in some line to see a holy person?* Anyway, we were a young and antsy crowd, until the moment His Holiness appeared and we spontaneously shut up and formed two straight, parallel lines, filing by, one by one, to be beamed at, comforted, and, in some obscure yet tangible way, congratulated. I became obsessed with waking up, and I thought - because Tibet, because the Dali Lama - that Buddhism was the way to do it. Pre-internet, I remember looking through the Hong Kong phone book, but the best I could find was Buddhist Utensil City, which actually didn't sound so promising. Luckily, there was also one bookstore with one shelf for books on Buddhist practice, in English. I set about reading all of them. I had no idea what any of this stuff had to do with potatoes, brains, winking eyeballs, thinglessness, or my life. One night, on a train bound for expensive gin-and-tonics on top of the Peninsula Hotel, I was reading Trungpa Rimpoche's talks to his first students in Boulder. "If you are here because you think the ideas are neat, but you've never practiced meditation, get out of here right away, and go learn. Don't do it in the Tibetan tradition - it's too complicated. I felt certain this was directed at me, this life, this waking up. I sought out teachers in Thailand, I learned, I decided to be a nun. I've gone through endless rounds of getting confused & thinking my work is to be a potato expert, losing track of waking up. But it's always come back to find me, moment my moment, step by step. Keep looking for this light. It is with you and it is within you; in the potato-painting, as in the blackberries on this table; in the bridge workers, as in the Dalai Lama. It is not a thing of expertise: it is a recognition and a birthright. Keep listening, letting go of any end, and it will keep showing itself to you in its many exquisite, almost unbearable forms. There is nothing you cannot feel, express, be part of. Be moved: this is the essence of waking up. *Actually, this happens a lot.

0 Comments

Something about Dōgen as an audio companion on my trips around the Upper Valley, something about strained homecomings, brought estrangement to this morning's practice. I started from the feeling: what is it like, when you're coming home from a long journey, and the one you've been longing for in airports and motels is like, meh? Is like, you don't get to call me your anything at all, because I've been monstering along unpossessed and free. What is it like when, whoops! you find you've actually been quite happy in the straightforward space of your solitude?

Dōgen says, Make the things of this world your enemy, and you will find clarity. That sounds like a recipe for profound estrangement, but it isn't necessarily so. Within the space of practice this morning, I bring up all beings everywhere who are estranged: from themselves, from their situations, from their homelands, from those who claim to know & encompass them. From those they want to claim and know, and who resist this with all their life-force and self-knowing. I see mothers welcoming home children who are ashamed of them, and children made to feel they are not part of the proper family. I see teenagers banished by homophobe families and good girls sealed off from everyone by that one awful night by the pool in the dark. I see young men seeing no hope in their homelands, and no hope in France, lurking at the Chunnel mouth for a chance to be estranged elsewhere. I see Greeks estranged from Europe, themselves taking in those estranged from elsewhere. I see married couples whose estrangement has grown into a thin grey film covering all domestic surfaces and vistas. It is a lot. A whole lot, and at the same time, a huge relief: All of us. All the gated communities and locked doors, the reactionary movements and revolutionary movements, the teenage angst and midlife crisis, the internecine warfare and the truckloads of antidepressants. Everywhere. In our estrangement, family. The heart, of course, has to grow pretty enormous to take all this in, but it's something we're capable of, something we know we can do. This too will be felt. And this. Usually, when we think benevolently about estrangement, there's a wish to find a solution for it all, creating a new context in the world, within which the heart does not feel mute, unwanted, irrelevant, distant. I think Dōgen & this commonality-in-estrangement practice are saying there is another way. We don't have to counter a worldly not-belonging with a worldly belonging. We can leave our belongings behind & instead find refuge in the space of the heart that knows things as they are, does not fixate on for-and-against, and has room for all opposites. The heart knows, Oh! That's belonging. That's not-belonging. Refuge is the space of knowing that is itself beyond estrangement and belonging. Whenever I am nearing some kind of big departure, waves of dying will come find me in the midst of ordinary life. I can't bear to be away from the dog! I love this street so much! This studio is an incredibly precious resource! This bed! This kitchen, knife, and board, and the big jar of walnuts! All gone, so soon! Here, I could say, There, there! You're going to such a nice place, and you'll be back home in no time. But that doesn't go to the truth of the feeling. Instead, I can acknowledge that this imminent departure is a kind of death, and agree to feel what I am feeling. I can feel this love and loss in its full intensity, allowing everything to fall away, because that's what it's doing anyway. I can offer up every beloved evanescent thing, sending it back out with gratitude to the mystery from which it came. Dog, house, studio, husband, sandals that work so well in the rain, ridiculous fishing pants, Tara thangka painted by my own hand, bossy rabbit pillowcase, plans, dreams, deerskin drum: all gone, given, and remaining. Not estranged, but released. Goodbye! Still here. Always coming home. Make the things of this world your enemy, and you will find clarity seems like possibly a problematic translation, and a merciful invitation to step out of the cycle of for & against, belonging & estrangement. Jesus said, Become passersby. He didn't mean, Isolate yourselves. He meant, Allow yourselves to feel completely, and then let go. I crack my heart open, vowing & failing & vowing again not to meet estrangement with estrangement. I do not make the things of this world my enemy, but I am learning not seek refuge among them, either. The climate change documentary I begin watching over rice-and-ratatouille begins with humpback whales swimming, diving, breaching, rolling in deep ocean bliss. Turquoise water deepening to indigo. Suddenly, my screen is filled with a whaling ship, shot from above. The harpoon rockets out on its line, the harpoon finds its target in the unafraid whale, tearing her tail, lodging in her flesh, destroying her, reeling her in, and I can't watch, I can't not-watch, my whole body flinches as the beautiful body of the whale is torn, savaged, pulled in without mercy, struggling all the way, an unclean kill if ever there was one, the whale winched in struggling to the maw of the ship, the drains spouting red into the ocean, dead space, dead hearts, unflinching stupidity "harvesting" beauty for what possible acceptable end? (I eat more ratatouille. No one hunts humpbacks commercially. Nevermind.) The story moves on. Climate change experts, crimes against humanity. Honestly, after that harpoon, humanity is the last of my concerns. Unflinching green climate expert eyes, showing whites above and below, a rictus of righteousness, holding little promise by way of compromise, compassion, and change. Life itself has ways of sorting out problem species like us. Not Atlas Shrugged, but, Being Itself Moved On. My friend Anna says she's sat in shamanic circles who've asked about climate change, What, then, shall we do? A collective hand-wringing of the sensitives, and the answer that came back was, Are you kidding? This is as far beyond your weather-working as it is beyond your science. Do your work. Get clear. Heal and release the whale-wasters and the wounded whales within you, so that you don't yourselves wind up as deniers or self-inflated prophets. Do your work. Heal yourselves. Being will take care of itself. There is a portal through which all energy must pass, say Anna's guides. What is dying now, and disappearing, will pass through and return in its new forms. White Rhino energy, Bengal Tiger energy, is energy that will find its new shapes in Being. We need to feel, but we do not need to be literalists, mourning as utterly gone something that is finding its way back through the portal. This is so. That this is so means we do not all need to develop the exorbitant eyes of the activist, nor the misty eyes of the professional mourner. This week a visiting artist came to my class, and there was much potential for flinching: unresolved work, very loose assignment, compassionate stagnation, the great man entering as an outsider with his ideas of greatness. But instead, what arose was a beautiful mirror. Here, Friends, is where you are flinching. Here are your fuzzy edges that help no one. What does it mean, when from within a kind of trance-state, you produce writing or painting that is in retrospect totally crappy? Does it mean the trance was delusion? Does it mean that craving viable objects as proof of extraordinary states is delusion? When I say, I am making art, what do I mean? If it is an indigenous process, whose doing is its own reward, then, what could it mean to show the results? Is it Bruce Nauman's The True Artist is an Amazing Luminous Fountain? Is it, witnessing the results of the artist's process is desirable, as a revelation of exalted states that are possible, even if inaccessible to mere non-artists? Is it, making time to view such objects temporarily removes the viewer from the distractions and predilections that otherwise keep her trapped? Is it, the artist triggers in the viewer a resonance of her own awe, her own melancholy, her own knowledge of the whale-harboring ocean from which we all arise?

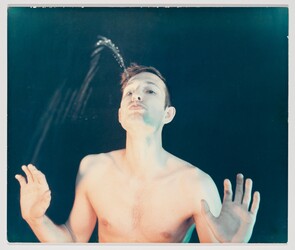

Anyway, what was on the walls was mostly messy, unresolved stuff, some of it sentimentalized, some of it trite, and yet underneath: young people making gestures towards becoming the singing whales of their own oceans. And our visitor, who describes his studio as a cross between a laboratory and a monastery, could see those gestures for what they were, though he could also see laziness & evasiveness, as unsuited to whale-refuge as scaly motel bathtubs. We flinch from immersion. We flinch from allowing the body-mind to die in life. I lay down on the studio floor, pull the nubbly cotton blanket under my chin, and resolve to die. Dying in the feet: feet don't want to die! Mind wants to think about next week. Dying in the calves: calves don't want to die! Mind wants to think about yesterday night. Dying in the shoulder blades: shoulder blades concede that dying might not be so bad. Breath says, We are dying all the time. Dying in the back of the head, I am dying with all who die, in their beds, in their accidents, in their battlefields, on the end of that harpoon, tail thrashing. Each breath in draws strength from the earth from the sky, each breath out tells those who die that they can do so unflinchingly, and be received. We pass through a portal, into the ocean, and are re-formed. I walk over the bridge over the White River, and know: Each time dying like this is clearing some of the madness from the world. Souls surrendered to the river do not hoard, recriminate, or shoot pain into others. The water flows very slowly south to the ocean, brown-emerald, clear all the way to the bottom. Here is a classic four-ingredient recipe for not-flinching in dying:

It's a hard recipe to follow, from within most of the structures we've set up for ourselves in the world. Academic teaching and learning occur within stupid structures. Politicians and voters make laws within stupid structures. Physicians and patients approach life and death from within stupid structures. All too often, religious seekers practice devotion within stupid structures. None of that means we're doomed to flinch. We can say, unflinchingly, No. That's not the way I want to go. Let's use these skills in this other way. Let's die more, so that who's talking is the Ocean-in-me, and not the flinching-in-us. May I, may we all, work to clear the way for the ocean to speak through us, without needing to tear down so many flimsy structures on the way. Not-flinching is possible for us all, as it is possible for each of us. It begins by noticing the things that cause us pain, and dying into them. Love is a joke, No one trully loves, says the table, in the handwriting of a young woman who will fall in love again. Her inscription is a footnote & rebuke to its neighbor, a wobbly felt-tip heart inscribed CM + GC. And she’s right: no one trully loves. Love is a joke in adolescence, falling for the same tomcatty cellist or soulful poet as my friend, and thinking the joke is on me, when, really, it’s on all of us. In high school there are a lot of jokes I’m not getting, including the outlandish one about how everyone is basically doing exactly what they’re capable of. Crazy as it seems, no one, including pyromaniacal erratic me, is holding back some better thing they could be doing instead. There are also some jokes I am getting that no one else seems to understand, except, blessedly, my friends. For instance, my friend Andrew and I understand that it is actually pretty funny how much suicide poetry we are all writing, as evidenced by his efforts & my own, as well as the overflowing literary magazine submissions box. Seen in this light, our adolescent laments feel more like a shared symptom than any cause for particular alarm. Andrew and I pull together a rogue anthology on the sly, and call it Death Be Not Trite. Few people get the joke, especially because we include some wretched poems dedicated to the kid who just died in a drunken car wreck. Nevermind. Love is a joke, and we are all in on it together. Last night, I dream of Andrew. I am in the middle of some complicated & enervating marketing scheme involving signed-unsigned products that may or may not be suitable for anyone to want to buy. And then, spontaneously, the market is flooding gently and Andrew is by my side. We swim around like manta rays in the shallow waters that have made all further marketing impossible. Then, in the dream, there’s a sticking/non-sticking point. Does all this swimming mean Love Forever? No, it does not. This swimming means the joke of love is the way it arises and ceases, forms and re-forms according its own nature, over and over. On the wallpaper in the orange room where we are standing awkwardly together is a golden decal of the Four Friends: an elephant, dog, bunny, and bird stacked on top of one another in search of sweet fruit. Swimming around in the marketplace is sweet fruit. Meeting one another as we very much need to be met is sweet fruit. Sleeping in my married-lady bed – which is mostly a me-dreaming-alone bed – is sweet fruit. Allowing the joke of love to arise and cease on its own terms is sweet fruit. In the dream, I go downstairs and find my parents have been cooking a huge feast of bright orange and green vegetables. Andrew and I are invited, among many others, even though swimming around like manta rays in ruined marketplaces is hardly my parents’ speed. The most amazing part of the joke of love is that it is unconditional and without fixed object.

Still, there are parts of us that will themselves to be arrayed-for and arrayed-against, despite all evidence of the impossibility of such distinctions. In my wish to scoot a tiny red mite off the page, and in its scurrying, I have solidified, and killed it inadvertently with the tiny grass shard I intended to offer as transport. Arrayed-for and arrayed-against do not leave the moment its own time to resolve. They want and don’t-want. May you be reborn at ease, little beast. Love is a joke that claims to specialize, when nothing could be further from the truth. The whole point of love is not-knowing, and turning towards groundlessness with an open and committed heart. Pema Chödrön & that lady who had the huge stroke that turned off the parts of her brain in charge of moving her right side, perceiving time, and ego function say: any emotion, unproliferated, actually lasts about ninety seconds. So now try building a solid story of True Love around that. If that were my daughter, I’d smack her, says the woman walking by with the puffy yellow comforter on her shoulders, to the other woman walking with her. Parental love is a joke in no small part because no one will admit how frail it is, and how undermined by the basic premise that it's possible to love close kin, while not giving a shit about all other beings: estranged kin, animals, trees, oceans, little scurrying red mites, people whose existence cannot be attributed to the loins of some putative shared ancestor or another. Trying to love your children as somehow special beings entrusted with carrying out your somehow special legacy is a joke. A terrible one. Much better to say, Everything is pretty much amazing, but you’re the little runt the universe has put into my care, so let’s find out who you are, and who I am, and what this whole thing will be about. Keep in mind, anytime I say This is the way we do things around here, what I am trying to say is This seems like a way we can be taking care of ourselves and the world right now. Try it, to see how it works on an open heart, and if something else comes up, please tell me about it. Timothy left this morning to spend a week with his family out West, and then another week with a friend, having Adventure Man Time. This is really good. May it go well, with all the aunties and grannies, cousins, awkward in-laws, and barrels of raisin bran, under the great western sky. May it go well with the canoe & the tent & the permits & the ropes & big rack, under the great western sky. May it go well with all beings everywhere, trying to break their addictions. May it go well with the tormented great artist and his manta ray sculpture, even though he’s still pretty convinced that in order to go deep, he has to keep on suffering. May it go well with all the deep beings and shallow beings, all the manta rays and Russian lady depth-divers. May the joke of love become the breath within the breath for us all, so that reliably, in any space, at least one being can remember not to fixate on love, or hate, or anything in between. Love is a joke and everyone is loved. Love is a joke that lasts about ninety seconds before being displaced by the sound of a truck backing, or a bird calling for love. Love is a joke with everything that can possibly be perceived as its punchline. Love is a joke requiring that the joker see herself duped, enlightened, and redeemed by grace, all at once. Love is a garment washed up on the shores of now, fitting perfectly, and yet so strange. Love chirps, beeps, settles, moves on. And in that moving on, any next line intended from an open heart is perfect. Stay married for 1,000,000 years. Become a manta ray of the marketplace. Sit down to the feast everyone’s been invited to. Stay present. Leave your mind alone. The joke is on, in, and of us all. Bald Eagle is a showoff, a wing-spanner, a dumpster-diver after the discarded guts of tourist salmon in every Alaskan harbor I ever visited. Bald Eagle is a miracle, an apparition, a bird flying around looking for lunch. Bald Eagle is a messy builder of gigantic twig collections, with downy squeakers in the middle. Bald Eagle will eat your cat. Bald Eagle will eat your Boston Terrier. Bald Eagle will eat your fear and die of it. Bald Eagle will fly on the steady rise of your courage, which might also be called persistence. Bald Eagle shits indiscriminately on patriots and fugitives, and much more often, on the empty spaces we haven't yet gotten around to Developing. Bald Eagle is OK with development if it involves throwing tons of its favorite offal in dockside dumpsters. Bald Eagle is even willing to be photographed, reptilian and strange, the object of every zoom lens in sight. Do you see? Bald Eagle does not give a rat's ass about your nation, or your religion. Bald Eagle is not aware that you believe in scientific application of pesticides, or that you believe in reining that shit in, so that her eggs may have shells strong enough to contain full-term eagle young, emerging frail, sticky, and ravenous into the world. All of that is human business. Go ahead. Paint Bald Eagle on your noisy chopper, your shiny bomber, and your eight-wheeled recreational vehicle, signifying freedom and fearlessness. Bald Eagle does not care. I am sitting in an empty room, where a Meditation for Well-Being class has been unfolding in the following way: nobody is here but me. I was born, and so I'm free, so happy birthday. It's stuffy in here. I walk to the Building of 1000 healers and leave Meditation for Well-Being postcards. I walk to the Co-op of Complete Purity and leave postcards. I walk to the empty room, grab my bag, and get out of town. I drive to the optician's and ask the lady who stood with me in the rain & helped me rescue my credit card about her trip to California, while she adjusts my glasses. We talk about how it would be great if there were a kind of vacuum tube you could hop into, and it would take you to the West Coast, without having to spend 16 of your precious hours in transit. Her colleague tells me her friend fell down the stairs and broke her ankle, because the vacuum cord took her down. We agree this is very bad. I volunteer that I avoid such risks by vacuuming as little as possible, which might be a different kind of bad. The California lady says, but probably you have a broom? Yes, I say, I have a broom. Sweeping reminds me of my grandmother, and my mother, she says. I love sweeping, her colleague says, just like I love hanging out laundry to dry. I'm probably the last person alive who still does that. No, me, too, I say. We are giddy with shared celebration of the ordinary stuff we do, that seems somehow exalted, even though you would never paint a clothespin on a motorcycle, and you'd never catch a bald eagle sweeping the dog hair out of the living room. I drop off cards at the Center for Holistic Healing, where I meet a guy who must be a therapist because he goes in the door marked Staff on one side and marked Great Room of Meditation on the other. He is so nervous his eyes are bugging a little bit out of his bearded face, and he is shuffling a yellow-and-red apple back and forth from one hand to the other, like a ball that he would very much like to lob at everything in the world that is currently making his skin feel too tight to contain his being. Like me, for instance. He shows me the Stuff Shelf, where stuff goes, and I carefully line up two Meditation for Well-Being postcards next to some other pamphlets. May it be so. I get back in the car, and decide on a route. Waiting in line for road construction, after the place with the two side-by-side gypsy caravans, I look up. Bald Eagle. For real? Yes! Bald Eagle is right up there, above the people sweating in fluorescent yellow clothing and hard hats, just wingspanning along, white tail, white head, looking for lunch, silhouetted against a cloud, catching the sun with every taut edge of her body. My phone goes, and it's the cancer anxiety psilocybin study guy. What? Bald Eagle and psilocybin study guy, all at the same time? I am answering carefully, and I am driving along carefully, though the road and the world are shimmering like crazy. My voice is calm and clear, and so is his. I realize this is a conversation I can have without needing to self-edit, and in that clarity I am being heard by someone who is receptive, grounded, interested, and interesting. Out of some form of modesty, I don't tell him about Bald Eagle.

Bald Eagle goes on her way. I park under the tree outside the park where we meet for Notebook Club. I don't know where this all leads, this driving along visiting co-ops & healers & centers for jiggly therapists & teaching classes where no one shows up & listening to unctuous-voiced actors reading the words of Tibetan masters. I don't know where this goes, this fire to be contagious & awake & receptive in the world. It goes here. Watching a fat-as-fat woodchuck snarfle grass into his little furry face, sitting with Larissa and Sam, being cooled by the breeze coming up off the river, now that the thick of the heat has stormed off. Bald Eagle is a psychedelic therapist. Bald Eagle is a woodchuck. Bald Eagle adjusts my glasses, so I can see the world, and then flies on. Bald Eagle is a religious professional, a shaman, a broom. The crows chase each other around the sky, and the trees sigh with contentment. Sorrow is everywhere and nowhere, just like well-being. If I had a motorcycle, I'd paint a woodchuck on it. If I had a broom, I'd call it Eagle. The hand, the mind, and the heart come to rest right here, while the woodchuck nibbles on. Sam and I sit under the trees in the park where the two rivers meet, and eat Syrian apricot cookies cast in Chinese mooncake molds. Adrian and I walk along the Baltimore inner harbor, past stacks of burnt-out plaster molds, from some mysterious foundry project unfolding in the swanky warehouse lofts nearby. Have they been producing artisanal garbage cans? Garbage cans are the only objects nearby of roughly the right size and shape. Education and religion are molds, and ideally their molding is a process in which the student or disciple adopts a chosen form and takes it on wholeheartedly. If entered into completely, the training form displaces other possible addictions and patterns, other ways of getting embroiled. The student applies herself to learning the shape of the mold and inhabiting it with her being. She is pressing life into a training pattern established by others who (hopefully) see both its usefulness and its limitations. Through study, she learns the mold's contours: which parts of her being are glad for its shelter, and which, obviously, yearn for a different shape altogether. She learns about resistance-energy, about the rewards of accepting a community's mold, and the costs. She begins to develop insight into being itself: the primordial nature that is not a mold & is not a being-molded. It is awareness itself, the awakening energy at the core of all that is, the matrix of all our patterns. Seeing this, she knows mastery of her chosen form, and, transcending it, realizes the formless. Ryushin Sensei grew in the mold of western science - a pediatrician and psychiatrist - and trained in the mold of Zen - the Mountains and Rivers Order. When I met him, he was Abbotting - teaching brilliant Dharma talks at Zen Mountain Monastery, residing with his nun-wife, Hojin, hosting genially at the meal tables in the great hall of the stone house in the forest. He was kind, amused by Elana and I, on retreat together, hilarious together, and he wanted to know what we were doing. Elana fed him cookies - a much better answer than my stiff lineage-talk. Just lately, it seems Ryushin has been either breaking or going more deeply into his molds. Darkly muttered Shamanic Interests. Deeply condemned Extramarital Affair. Bad-boy confession, six-month exile, reproof. All of it very Somebody. I am reminded of the end of the Earthsea Trilogy. Ged has gone into the dark to restore the integrity of the border between life and death. He's come back with the Rune of Peace, revealed his young fellow-traveler to be the long-awaited King, and arrived on the back of a great dragon. There's to be a feast for him with songs and more, but instead, Ged gets back on the dragon, his friend, and flies away to his obscure island home. He has done with doing, someone says. That seems the way. Stepping down, stepping out, letting go of Sensei, and going out into life unfixed by any mold. Much later, when Ursula Le Guin returns to Ged in her writing, she makes him a moody goatherd. All his magic is gone, and so he is ready for an open life, a life with room for the ordinary-extraordinary roots of love. May it be so for Ryushin, as for us all. Wei wu wei. Doing not-doing means acknowledging that the molds have never really fit, and the desire to force a match is gone. No more sliced-off toes, no more sliced-off heel, no more glass slipper, no more Princess. Margery says, Kung fu means mastery. It means whatever you are doing, you do it with full presence. It's transferable, and, in the style of many-armed Kuan Yin, it's adaptable. Why harden around identifying with one way of being, when the next situation will require another? Much better to develop the ability to fill any mold with skill and discipline, and then to set it aside gratefully, as soon as its usefulness is done. Not a tai chi expert, or a meditation expert. Not a painting expert, or a cooking expert. Just being, skillfully. This goes against the logic of the world, because constantly embodying & moving on leaves little trace. How will I be recognized? How will I be praised? Maybe not at all. Maybe it will all seem squandered. Maybe Most Horrible, I will never give a TED Talk.

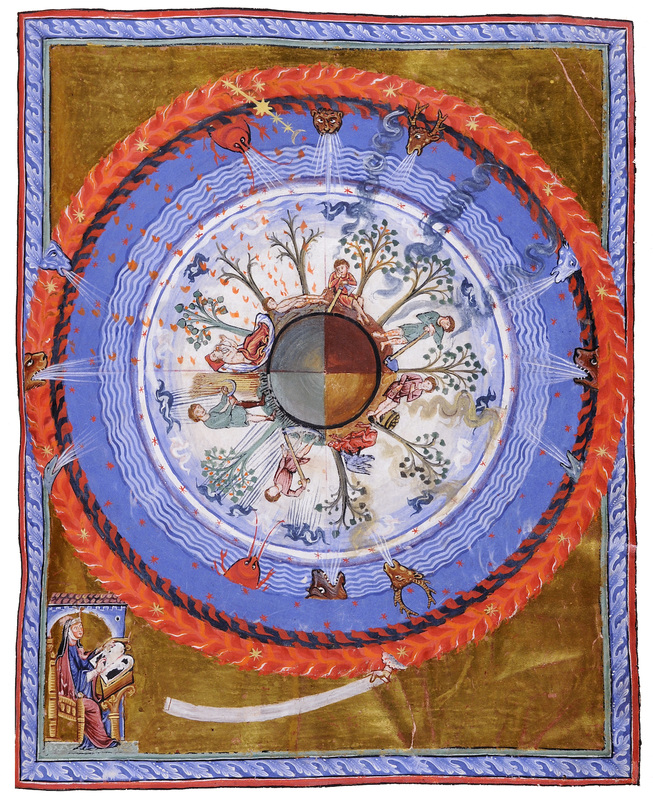

But, when I sit down in the second row of the Baltimore-Boston flight and realize that I've somehow joined the Unaccompanied Minors' Club, I know what to do. Open. Let go of other plans and preoccupations, and listen to two 12-year-olds' stories about water parks and grandmothers. Use their sharpies to draw a cheetah & a birthday cake. When the boy by the window says he is "dark" and likes to draw "dislocated" people, ask him if that is because something very painful is happening in his life. When he says, My mom, wait a bit and ask if she's sick. When he says, She used to beat me, and that's why I'm going to live with my grandma, and that's why I like to draw her, dislocated, tell him there's nothing wrong with him. Tell him he's a great kid. Tell him he'll find other ways of working with his pain, besides more pain, and anger. Listen to Katy Perry's Roar together, and, descending through the clouds, add red Jordans to the cheetah. As for the little girl, listen to her love for her Nana, and admire the Febreze-scented Pooh-Bear doll that takes up 2/3 of her carry-on luggage. Agree, definitely, that her older sister, Madison, is nicknamed May-dog, and NOT Maddie. Listen to the lore of her hamster, Thor, with his long blond hair, and, lo, the lore of the hamsters who came before him. The boys says, We will meet again, and I will be 10 feet tall, and you will have white hair, and I will be your favorite student. Yes, why not, may it be so. Her stylish Nana is waiting, with her good haircut. His aged Grandma is waiting, an oxygen tube in her delicate nose. They cry together, molded into an embrace of love and relief. Hang in there, old lady! This kid will need refuge for a long time. Not the mother-mold, and not the not-mother-mold. The endless, shifting shapes of presence, response, creation. I wouldn't trade this dance for anything. At the beginning of the session, while my guides & I were looking at a book of mandala images, mostly from nature, I noticed in particular an image of one of Hildegard of Bingen’s illuminations. It is the four seasons, I think. Large animal figures are blowing the winds in towards the world, from the four directions, and maybe angels are turning the keys that move the world. In the bottom left corner is a tiny alcove, in which sits Hildegard, in her nun’s wimple, recording this vision in a book, using a quill pen. Seeing this illumination at that juncture was auspicious: it reminded me, throughout the session, of the possibility of being fully within whatever was arising, while also grounded in this body & mind. It reminded me that at any time, I could reframe my experience, and go back to the alcove (the body, the mind). It reminded me that whatever was about to happen, Hildegard & others like her had probably been there before – I have had this sense with other experiences – and I was in good hands. As my experiences began to shift and deepen at the beginning of the session, I had an intuitive sense of, Oh, this! I know this! Sort of like a homecoming. There was nothing in it I felt I needed to resist, and in fact I knew that the less I resisted, the better things would go. This might sound odd, but a previous place I had felt this sense of informed and wholehearted consent was in getting my wisdom teeth yanked a couple of years ago. I liked the dentist, and I trusted him. When he started on the first tooth with the pliers, and the enamel started making shattering sounds, there was a moment of real fear. But then I thought, You have come here to let this man take your teeth. Let go! And the first tooth came flying out. The second one took a little more doing, but soon enough, it was out, too, and both of us were delighted to see it, gnarly & slick with blood, as its sister had been. He had freed me of teeth that were no longer serving me well, and I had worked willingly with him to make this possible.

Let this be for the good of all came up as I passed from one state into the next. I could feel I had no expectation of what ought to happen, or what I wanted to happen, and I could feel the commitment to allow this for the good of all consciousness to form my intentions throughout the session. The insight arose: any point within this experience can be an opening into the infinite space of open awareness. I found this was true, just as I had found it to be true in working with Reggie Ray’s embodied awareness practices, and with tai chi training. I reached a place of feeling at ease and stable, having in some sense crossed over. I could focus my awareness on the body, relaxing the legs and feet and face. I could welcome awareness, and allow it to deepen without limit or obstruction in any sense or any direction. Then arose the insight of suffering: beings everywhere imagining themselves to be separate and isolated, when in fact we are all participants in – and embodiments of – awareness. I turned back towards this suffering with a sense of profound grief, and also knowledge that my vows and my intention meant I could not shy away from it. Beings are numberless, I vow to free them all. Delusions are inexhaustible, I vow to let go of them all. Dharma gates are boundless, I vow to enter them all. The Buddha way is unattainable, I vow to embody it. I remembered two photographs of my father I had looked at the night before: 1. my father is in an airplane, sitting next to my little nephew, and looking really creepy: grey, puffy, fat, sweaty, hairy. next to him, the boy is sweet, perfect, shy. my father is trying to protect him, but his idea of this is plainly insane with worry and control. 2. my father is holding a bunch of orange dahlias, and beaming at the camera, at my mother, at my nephew. He is still in the body of a man who eats too much, and probably drinks too much, and works too much, but he is radiating pure joy. the picture is captioned in pencil, in my mother’s writing, Goompa’s pom-poms. Goompa is what my nephew calls his grandfather. I found myself entering the state of being my father: the heaviness of an unloved body, the way he tends not to see his inherent good qualities & is thus constantly laboring to justify his existence and stave off annihilation. I found myself entering into the being of my mother & brother in this way, and then my husband, and my dog. It was hard to go into the dog: the distance felt greater, and also the grief. On retreat three weeks ago, I studied the Vajra Songs of Longchempa, which include the bodhicitta that exchanges self and others. In the next phase of the session, I found myself doing this literally. Exchanging self and other: entering into the consciousness of others, now without the layer of grief I had felt so deeply, earlier. The insight arose: if I am in here, awakened awareness is in here, and so within any possible state of consciousness, awakened awareness is present. No one is alone. No one is cut off, whether they are conscious of the connection, or not. I found myself traveling back to a resort in Bali, where a group of followers of an enlightened Australian man were staying. I could see all of us there, at breakfast, eating fruit & honey & delicious red-rice bread. I could hear one of the disciples telling me about her teacher, how amazing he was, and I entered into that mind, where I saw there was a spark of awareness that knew this whole thing was a game: she was primordially just as awake as anyone, and while it was fun traveling to Bali to be with An Important Person, ultimately the task was to be in her own true nature. I visited some Klansmen at a rally in South Carolina: what are you up to? I could feel that part of the pain they were experiencing was the internal knowledge of falsehood, which needed to be staved off with ever greater displays of aggression. Throughout all of this, there was a sense of not clinging to anything, of allowing consciousness to travel. Sometimes I felt a sense of pause, of gathering. To what shall I apply this consciousness now? I found if I waited a bit, an answer would come. Either it would be time to shift into one of the meditation sessions, or some new imagery would arise from within the music, or elsewhere. I could feel it was important not to become attached to the stuff that was happening, and to check in with the space of awareness itself, resting there. I felt aware & immensely grateful to the lineage of teachers, known and unknown, who have kept the teachings of primordial, compassionate awareness alive and available in this world. The meditation sessions were welcome. All three – breath, metta, open awareness – were felt as expressions of the same seamless consciousness. At the same time, each one was like a stone thrown into a pond, causing different ripples. I was aware of being grateful for the opportunity to be a good citizen, and let go of whatever was happening, in order to focus on the room, and my guides, and the meditations. I was aware of taking pleasure in good citizenship, and in not indulging in focusing on the extraneous, exotic elements of my experience. True, one of my guides was giving off rainbows, and it was a little harder than usual to tie my pants, but, c’est la vie. The end of the session felt sweet. I could tell I was returning to something more like where I tend to spend my days, and the music came to feel like a lovely line back into the world. I felt like a kid in bed, listening to her Walkman, and enjoying the beauty of the sounds & lyrics. Ladysmith Black Mambazo singing Reveal Yourself struck me as especially moving and apt. I am immensely grateful for the opportunity to do this work in such a beautifully supportive and well-thought-out environment. May these insights and experiences be for the good of all. Something's cooking in that plastic bag from the co-op on the ground over there, next to the empty triangular sandwich box. We don't really want to know, and it smells bad enough that we are going to move to a different table. Poo? Garbage? Death? Something's always cooking, and if it weren't, there'd pretty soon be no room left for everyone. That's what the old lady in the deep-quarantine section of cancer-town said to me, that afternoon, pale wintry light filtering in through the window by her bed. She'd just been telling me about how much she loved her life, her daughter sitting by her side, her grandchildren, all the places and people she'd given her heart to over many decades. Oh, I'd love to keep living if I could, she said. And then, looking me straight in the eye, But if I could, so could we all, and then the world would get awfully crowded. She'd had her turn, and loved this life so much that she was willing to give it up, for its own good. We start off sort of sparkly, but underdone, and gradually mellow into the deep, funky flavors only possible through surrender, transformation, and decay. We Roquefort. We kimchi. We go deep. Our capacity to be delicious is infinite, though elective. There are beings who become more intensely flavorful as they live on, and others who soon dry up and get rubbery. Of course, we can choose to be re-born, re-basted at any time. It all comes down to: what do I think I am? If everything, then some seriously special sauces will make themselves available throughout life. If this little thing, then the juice runs out. That's about the shape of it. Yesterday, hungry after teaching , I wandered out into the sunny afternoon in search of something to tide me through grading and tai chi. I entered the dim, fancy confines of the underground place on the corner. Cakes, cookies & chocolate bits, all of which I steered myself away from & towards the quiches. Leek and goat cheese. OK. $7.10 later, with an extra $1 to the tip pot, for the lady with the winged rock-and-roll mudra on her chest (at least I never have to do THAT again, she says), I am sitting on the strangely low, broad red couches of the art building with my food. Expensive quiche: thick, bland butter crust, thick, bland creamy filling. It's not actually very good, tasting of small-business insurance, no-risk guarantees on handmade mattresses, and the boredom of institutional cooking, where no one's allowed to grab the pot of paprika with a mad gleam in her eye, saying THIS! THIS is what quiche tastes like today! Still, it's food, and it does a fine job of keeping me grounded through seven students' worth of projects, before heading to the river. I quit working in commercial kitchens when I realized I am completely uninterested in producing the same thing, reliably, time after time. I am interested in what THIS moment tastes like. I am interested in licking the spatula straight out of the food processor, to see what today's pesto is like, and gobbling it up while taking sips of glorious icy-sweet lime-slice gin and tonic. I'm interested in resurrecting the gamy and the dead - taking the world's flawed and leftover ingredients and combining them into forms of deliciousness that are irreproducibly born of this moment, with all past experience woven into now, but not dictating it. I am a disciple of the unbinding of the pantry cupboard and the refrigerator - how ingredients sourced, grown, given & bought suddenly come together in their own extinction and rebirth. Now-soup! Now-spread! Now-pie! I am drunk with making, I am reading the fullness of the world in this kitchen, abandoning what is not in favor of What Is. This body is made of such feasts. This body is a vehicle for feasting, a feasting-magnet, celebrating the plenitude of the ordinary. When I first started cooking in this way, I was living at Amaravati Buddhist Monastery, in the countryside outside of London. Some of the very basic ingredients the community had to cook with were purchased from supporters' cash donations, but everything else depended on a lottery of generosity. Unpacking the plastic bags left in front of the altar during big Sunday gatherings, it was possible to guess who the donors might be. A Thai lady working in a restaurant. Not much money. Bit of greens, white rice, soy sauce - what her grandmother might have put in the bowls of the monks walking barefoot through her village on alms round. A suburban middle-class family, into holistic health: sealed packet of organic baby corn, organic tinned chick peas, miso, organic broccoli, nettle tea. A family with small children: granola, white bread, chocolate candies, digestive biscuits. Out of this disparate array, each day a meal needed to be conjured for 60 people who ate breakfast (huge pots of tea & gruel) and lunch (whatever-miracle-buffet), but not dinner. Each day there was a Head Cook, who took advice from the kitchen manager, an eccentric Croatian monk who eventually disrobed, went back to being Zoran, and struck up a relationship with a formerly fearsome-seeming lay member of the community. Zoran liked to wear a purple velvet tea cozy on his head as a sort of papal toque. His authority, thus affirmed, was important in reining in the devotional zeal of certain Head Cooks who otherwise would have appropriated all the best ingredients for their own efforts. I learned to like cooking with the stuff nobody wanted to mess with, because it was weird, or there was hardly any of it, or it was bad for you, or whatever. This practice of taking manky bits and cooking them up into something sustaining and good is interrelated with the Bodhisattva Vows: beings are numberless, I vow to free them all; delusions are inexhaustible, I vow to let go of them all; Dharma gates are boundless, I vow to enter them all; the Buddha way is unattainable, I vow to embody it. Ramen stew and twinkie pie, I vow to free you all. Fears of poisoning, allergy, fattening, and skinnying, I vow to let go of you all. Impossible arrays of mismatched foodstuffs, I vow to enter you all. Perfect meal of unbounded generosity, I vow to give you form.

One winter at a sister monastery, I did get really skinny. I was on three-month monastic retreat, and the two sweet young men in the kitchen were consistently not preparing enough food so that I, at the end of the line, could have anywhere near the amount I usually ate, and leave anything for them. So I shrank, to the point that the window in my sternum became visible, and my ribs stuck out. This was good practice: here is what hunger is like. I've thought all kinds of things about food, and I've gotten sick all kinds of times: from plague-bearing clams in Tsim Sha Tsui, and from Delhi's awful sludge, clinging to the delicate skins of the cucumbers I couldn't not-eat on a sweltering day. In all of this, something's cooking. The Buddha died of someone's cooking, to make room in the world, to allow himself and all of us the liberation of an ending. So it goes, and so it will go, world without end, Amen. Lately, Chloe's taken up air-humping our house-guests. It's something new and fresh for all of us, growing out of the trauma of her surgery and having to wear the Very Large Array for weeks. Also, less dramatically, it's part of the basic condition of being a house-dog. Chloe's air-humping John and Sunny, and Iseec and Leah, is a way of testing the waters. Who am I, here? How will these people respond to a little test of Chloe Is the Queen Around Here? And the wonderful thing is, we are all doing this all the time. Women who walk into a room and reflexively scan all the other women's clothes and hair to see who's got what going on. Men who scan a room reflexively for fuckable options. Travel-stories and kid-accomplishment-stories; stories of this Tibetan lama, or that. All of it is total air-humping. Will they notice me? Will they hear the name of So-and-So Rimpoche in association with mine, and forego the sharp teeth they would otherwise fasten around my neck? That would be so nice. So nice not to have the fangs, the blood, the humiliation of being on the ground again, pinned under immovable weight again. My kid is learning to sail in France. I got promoted to deputy manager for international operations. Please don't cut me open. Students do this. I'll explain an assignment what seems like straightforwardly, and then there's always someone who wants to air-hump their way out of it. This dynamic is very different from those who just hear the assignment, let it process through their awareness, and go do whatever they're going to do with it. Those ones don't have any time for air-humping, because they're too busy making art. They vanish, go find what needs to find them, and come back radiant with discovery and self-confidence. Meanwhile, the air-humpers - and this is pretty well all of us, at one point or another, a transpersonal force - want to be affirmed in their transgression. We can't face going to dwell in the unseen. We need assertion-with, or assertion-against. My teacher says. My party says. My great-great-great grandfather, Nathaniel Bedford Forrest says. On and on. Chloe, living with a gimpy leg, outside her species. I get it: confusing. Rules not her own. Get used to these two goofy humans, and then here they come, bringing new ones into the house, with bottles of wine, foot-cream, and Zionist flags. Now what? Yesterday, I read this: That the self advances and confirms the ten thousand things No self to confirm: awakening. Embattled self always seeking affirmation: endless air-humping, plus fangs. So it goes.

Chloe, Chloe. Such a happy animal sometimes: prancing on her wolverine-feet, smiling her little lower-teeth smile as I pull together poo-bag, hat, leash, shoes. She doesn't need any of that. She's ready in her suit and shoes anytime. Her ears ready to hear, eyes ready to see, paws ready for the ground in all its forms. Three paws firmly grounded, one more tentative. Chloe poops brazenly on Jack's immaculate lawn, seeing only: this green world. She eats blades of long, fresh grass, savoring the summer through her curling pink-black tongue, bringing the world into herself, herself into herself. There is so much air-humping in religion: lovely, simple gestures that have hardened and lost the freshness of discovery. Everyone apparently knows to bring a white silk scarf along when it's blessing time with a visiting lama. We bow, we put our scarf around the holy one's neck, the holy one puts it back around our neck, we bow again, and pack up for the next time. Hum de dum. The gift and return are beautiful in intent, but what about all of us instead tying our scarves end-to-end, and playing twister? Or mummifying ourselves in blessings? Wrapping Tara in silk until she is a tufted titmouse, with golden toes and bun protruding. There are more possibilities than we know & it is good to go into the dark and find them. Air-humping the house-guests. Everyone's met a bad dog and the people who enable her. My grandparents used to blame my brother and I when Fanny the cocker spaniel would jump up and bite us on the ass. Fanny had no time for air-humping - it was straight to the fangs for her, and no hesitation. Something about my grandparents' régime brought this out in dogs - Tessan was a toe-biter, and poor Bendy was put down after mauling my grandfather once too many times. He was a golden boy, all blond feathers, and not nearly enough no. We don't give house-dogs room to go into the dark and figure themselves out. Farm dogs are different. They have a world to roam in, and a job to do. They will show fangs when needed, and as for air-humping, why bother with that, when the real thing is on offer, with that feral coyote in the windbreak? The vet thinks part of why Chloe's knee is damaged in the first place is that she was spayed too early, and so her muscles & tendons & bones & ligaments didn't get the hormones they needed to knit up strong. Poor beasties: we are so concerned with securing their well-being that we stunt it from the beginning. No time for the dark: the force of reason requires the light, the rational solution. No time for Moonbear pups for the Moonbear to lick & suckle & protect. We have gone a long way together. We are good at making ourselves lonelier. We do the best we can with what arises, and try, again, again, to tune to the mind of discovery, of neither for nor against. We put the dog in the crate in the dark for awhile, and then pay close attention to what emerges, smiling with little lower teeth, and eating marrowfat in the corner of the kitchen. We meet here, under these trees, to look into what is, to know this, and that, and to choose wisely. We let our loins rest from air-humping the world, and we relax. Because Erica’s getting older, there’s a lot less to worry about, on the cosmetic front. I mean, when you’re 17, it makes some kind of sense to buy & even to apply teal eyeliner, magenta lipstick, foundation goo intended to laminate your zits into hiding, but let’s face it, as Erica and I are getting older, we don’t give a rat’s ass. Sometimes it still happens that I see someone with perfectly applied swooping black wings on her eyelids, and I think, what a glorious thing! But then, in CVS, with my 2-for-1 deodorants and fluoride rinse in hand, I just can’t find the self-seriousness or the stamina to face the endless wall of goony-eyed models, select a vial of product, slide it out of its glamor-silo, and pay $17 for it. It just doesn’t happen, because I’m getting older, and so later, when it rains, I don’t have to worry about blotchy, itchy flakes of black in my eyes. I can cry with abandon, and not feel I am ruining anything. I can fall asleep anywhere, wake up, rub my face, and everything’s fine. I used to be a real zealot about my black lines. On the long flight to Tokyo, when I was 21 and wing-eyed, the flight attendant asked me whether I was part-Japanese, because her child was going to be, and she was hoping her daughter would look like me. A guileless and flattering thing to say, though only really possible from the perspective of looking down at my 6-foot body. I told her I knew her children were going to be beautiful. I carried my Revlon liquid liner all around Shikoku Island, walking with a backpack full of film & books & only partially effective rain gear. I could not imagine letting the world see me without a decorative awning, even though the world was mostly temples, rice fields, and the old people who had bent in them for centuries. They didn’t care. I cared. I slowly learned not to in the subsequent years’ travels. I learned to see my face naked and accept it that way, and not need to put black lines between my gaze and others’. Then for a while I wore enormous British National Health Service glasses with thick lenses that created their own kind of distance. Because Erica and I are getting older, I am pretty sure that 4th of July anxiety doesn’t apply as much anymore. I mean – I’ve known all kinds. Most of the first 16 or so were spent in France, where the 14th was the real deal, and the only people paying any attention to the 4th were the American sailors on board the destroyer they would park in the Baie de St. Tropez like a great gawky stretched-out Escalade puffing its uncool chest outside a club everyone else walks to. My uncle, unwisely, pointed his little grey rubber Bombard at it, full-speed, gesturing and yelling Poussez-vous! A stunt best done before The War on Terror, in the bare-breasted 1970’s, to be sure. So the 4th of July is historically not my thing, except for one spent in San Diego with some friends of my parents. We went to picnic by the harbor, and stayed for the Pops, followed by tremendous fireworks: a whole American flag at ground level, with larger explosions above, and parts of the great American fleet looking somehow flat-grey and festive at the same time.

When I came back to the US from the monastery, suddenly the holiday arose with a whole new urgency, showing me I knew no one to spend it with – at least: no one whose family space would include me. I felt a sharp pain at being left out of what claims itself as everyone’s holiday. Not everyone’s. I was deportable. It was not clear where I could be. No country for bald women. Ashamed of loneliness, I felt it more keenly. But now I know. Sit still long enough on the porch, reading out loud to myself, and sipping on a gin and tonic with cucumber slices, and a hummingbird will come to hover snoutily at the delphiniums, and dart away to its home, far away over the sumac. The feeling of one-ness, now-ness, sacredness, and participation will seep up from the ground, and drift down from the sky. It will open from the heart of its own accord, 4th of July or no 4th of July. There may be pie, or not. Sacred space is here. Here under the wide shade of the river-fork trees, here where crazed chipmunks dart up the linden trunk, in the lee of the parking lot, in the lull of the traffic, in the shelter and company of all beings who take refuge without begrudging the moment anything. Because Erica and I are getting older, because I am getting older, I am better at filtering out and filtering in, though it’s still hard for me to say no when obligation arises. No, I will not bend myself into crazy shapes to meet a need that comes up like a rumor of war from another country. No, your perception of emergency does not necessarily involve me. The trees smell good here. I have my own work to do. May yours go well. I think it’s very important to know that we meet at very particular points in vast rolling cycles. Ask me one morning, coming from your own spaciousness into mine, and there will be effortless, obvious yes. Ask me two hours later, after the locked doors and obstacles of a new batch of emails, and I won’t be able to find a truthful yes for you. If I’m careful, I won’t lie one up for the sake of decorum. I won’t paint the black lines on, and you’ll be left to decide whether to drop it, do it yourself, or ask someone else. Truthfulness is changing because I’m getting older. Not the young woman’s crusade anymore. More like the older woman’s considered evaluation of what’s happening in nearby territory, and in the inner hinterland. What can be said and heard? What can be said and not-heard, but needs to be said anyway, because it’s cowardly or condescending to hold it back? What deeply uncomfortable truth needs out, so that the illusion of an infinitely competent and energetic self gets laid to rest again and again? Because I am getting older, I know exactly how much I relish bed at 10PM, the fat science fiction novel and the succor of pillows. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed