|

There is a mayfly on the ceiling. Maybe it hitched a ride from the river on Sam's hat.

Years ago, when I had left Drew because he told me to, I read Melissa Banks' The Girls' Guide to Hunting and Fishing. An odd book about a woman roughly my age, navigating her way through loving her much older editor, and some other men I can't remember, before winding up one summer's day at a wedding reception. Across the assigned table from her is an unknown man, and in response to this man's presence, she feels hot, sick, dizzy - not herself. What is this? She felt perfectly OK earlier in the day. Then she realizes: she is attracted to him. That's it! Eventually, the two go on a date. Mayflies are clouding, lolling, flapping, and dying on the lawn & tables & road & everywhere. She says to him, They live for one day. They mate, and then they die. At the end of the book, he says to her, I want to mate with you and die. A more honed-in thing to say than, Will you marry me? Anyway, it works. The book works. The mayfly works. It was that book that helped me to figure out what was going on, the night I met Timothy. Like the woman in the book, I had more or less given up on being attracted to anyone I actually met (Aragorn does not count). Internet dating had been interesting: the sweet mathematician I met in a gravely parking lot at the base of a mountain; the bower-bird hacker who'd re-jiggered the code for his profile page so it included features no one else's had; even the boring, jaded guy who kind of but not really wanted sex after eating tater tots together outside some bar. All had something to teach. None were attractive to me. Then this Timothy Rosenkoetter. I want to mate with you and die, I thought, while simultaneously wondering who this tall man was, to be coming towards us with such a happy lope. That bug on the ceiling is now nowhere to be seen. Is it free? Did it find a way to get out and go be a mayfly on its one day? I hope so. I somehow suspect not. We will have to look this place over for languishing insects before we leave. That bug on the ceiling is sometimes a gecko, calling and calling its name from within the thatch. Dropping squelchy shits onto the floor below, which you have to watch out for, barefoot and in the dark. Or it's a tarantula weighing down a first-sized divot in the mosquito net over your bed. In that case, you have to shine your flashlight on it and get the German girl you are bunking with to understand the problem and help you escort it outside without more than a strangled giggle escaping into the silent retreat night. Sometimes, in the argot of my mother's family - avoir one araignée au plafond - the bug on the ceiling is your own preoccupations and obsessions. Your worries and imaginings. The paranoia of the world coming to roost in your mind as a wooly black arachnid - though not a brown recluse, as I've just learned from Larissa, because they don't climb. Hear that, bug on the ceiling? You may be doomed to entombment in Notebook Club purgatory, but no necrotizing spiders are going to come and get you up there. Spider, spider. I remember one night when we lived in Fresno. My mother was wearing one of the ruffled bandeaux she would sew for herself out of my father's worn-out shirts, bespoke, pearl-buttoned, monogrammed shirts my grandfather used to order for him, Place Vendôme. He got Rhodès & Brousse, and she got scraps. This one was maybe white with orange pinstripes, because it was the 70's. My mother stepped out the side door carrying a brown paper bag to put in the garbage. From the dark, she screamed a bloodcurdling scream, and my dad leapt up to her aid. Then for a while all I heard was grunting and thumping. They came back in: a tarantula had landed on my mother's chest, and my father had smashed it to a pulp. All this made me sad: my mother's inability to protect herself, my father's brutality, and the tarantula's rotten luck. I became aware of the possibility that in addition to scary dogs who woofed deep while throwing themselves at the shuddering backyard fence, and kidnappers who dumped the bodies of dead babysitters behind trash cans, and deadly wounds incurred during careless play, the world nearby contained enormous spiders that must be murdered in manly rage. Years later, my father found a Black Widow in his Volvo, parked outside the engineering building where he taught. I do not know if he managed to crush it, but I do know he felt someone had put it there. Maybe it was the long-traveling, persistent ghost of the tarantula. In comparison, the nightly snail and slug raids on which my mother led my brother and I were light-hearted affairs. She would pay us X (5 cents? 10 cents?) per squished gastropod. We would go out at night hunting for them with flashlights, under the flowers and the vegetables. We would pause to look up for shooting stars or satellites - maybe even Skylab, before it fell to earth. My mother's mother was also a bug-hunter. In the south of France lived voracious, plump, new-green grasshoppers she called bougrane, after the Provencal boudrague. Mimi's garden near Sainte Maxime was beautiful: brick-paved walkways, kikuyu grass, bougainvillea, lavender, witches' fingers, wisteria. But it was also a combat zone: there were bougranes to crush underfoot on the brick pavers, and ants to poison using some evil ersatz honey they were drawn to, and, altruistic, would live long enough to bring back to their colonies, killing everybody off neatly. One summer, some unusually large lizards came to dig themselves warrens in Mimi's lawn, just outside the sliding doors to our bedrooms. They would sun there watchfully: the green one as long as a man's arm, the brown one as long as a woman's arm, and the little green one, maybe the length of my own child-arm. But they also ventured further. Once, talking to make a point, as he often did, my uncle felt something jerk at the pair of cherries dangling from his hand, and we all turned to see the largest lizard dashing off with her prize, feet flying over the fine, grey gravel. My grandmother believed these - what? iguanas? - to be useful in her overall grasshopper-eradication scheme, and so she forgave them their thefts, and treated them with benevolent inattention. The following year, they were gone. Bugs, bugs. When I lived in Hong Kong, there were epic centipedes - brown-red, patent-leather, thorny legs protruding from between each segment. They were held to be poisonous, but how? Claw-touch, mandible-bite, skin-to-armor contact? I only ever saw a few, but I knew they were there. Once, on the slimy stairs leading by hundreds up from the train station to the hilltop where I lived, I saw one smashed, and felt sorry again. What is a world without monsters? Years later, in the Dominican Republic, I reencountered these at a low point in my ill-advised honeymoon. (The beach? For two people who are bored by the beach and sunburn easily? A land of bland, stringy chicken, for two people who like good food?) Anyway, we'd both caught dysentery and were squitting our way through a long, sweaty night in an old stone house, when Timothy let out a terrible yell, and bounded I swear across the room in one movement. A giant centipede had been crawling on his chest. No bite, only terror. About an hour later, it was back. Was it saying, I want to mate with you and die? If so, he was having none of it. In the morning we left, to trundle back to Cabarete in the little rental car whose donut-sized wheels could barely clear the road's weirdly inverted speed-troughs. Everyone else seemed to know what to do: carry donkeys, drive around with propane canisters and babies. We had yet to learn.

2 Comments

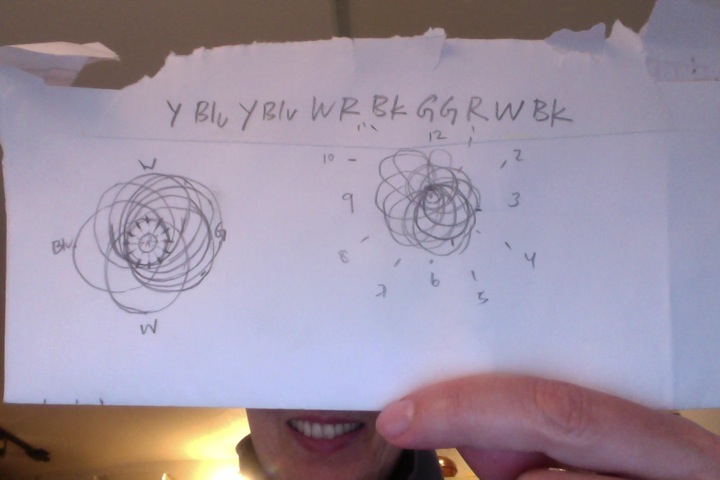

Some part of me relaxes deeply & exults within the process of crafting highly detailed, intricate things, especially if they take a long time to execute, and embroidery is involved. It makes perfect sense to me that Yayoi Kusama engages in her dot-universe as a way of managing her anxiety, just as it makes sense to me that sailors on long crossings would carve scrimshaw. That's just the way it is. A few years ago, my mother and I traveled in Bhutan together, and I found, to my great delight, that Bhutan is the Land of the Detail-Obsessed. So much there is beautifully made, crafted with precision, care, and humor. (From my perspective, this inclination must be connected to Bhutanese Gross National Happiness.) Here's a photograph from within Punakha Dzong, an amazing temple/palace where the Mother and Father rivers converge: Every little bit of that facade is carved, painted, gilt, and tweezered together into an almost hallucinatory degree of beauty, which includes, to the left of the entrance door, this Cosmic Mandala: (Actually, this is a reproduction that I commissioned from Pema Tshering in Paro, and which now lives with me in NH.) Summer can be a hectic and distracted time, so as an antidote and a joy, I've decided I want to embroider a version of the Punakha mandala this summer-into-fall, choosing to anchor myself in the elements' beautiful dance. The first step on this path is to figure out what exactly is happening. Even though I've been living with this painting for years, I've never before tried understanding exactly how it's made. Now, I see there's something spirographish happening, and also something like a clock, with "hour" markers dividing the circular structure into 12 parts. I realize that each marker is the center of one of 12 circles whose perigee (in relation to the central figure) is the opposite marker. So, for example, the circle centered at 12:00 has its perigee at 6:00 and its apogee at a point equal to the distance between 12:00 and 6:00, somewhere out in the watery field. There's a lot that's still mysterious: What explains the pattern of color alternation? Why are some color pairs far apart, while others are close? I know the answers will come as I need them, and for now, I know I have enough to get started.

In pain, tissues expand. It is just what they do to cushion themselves from further harm, to pad one irritated part from another. To isolate from pain. It works, but it works in a way that can be hard to reverse. When is it safe enough to contract again? Answer: never. Answer: there will always be some lost soul out there with such pain that it has expanded out into the whole world he traverses, with his bowl cut and his starved eyes, his Rhodesia patch and his birthday gun. So, no, strictly speaking, one would be forgiven for thinking it is never OK to contract again, to take down the armor of extra, to be safe again in the confines of the body in its naked, un-irritated dimensions. But no end of suffering lies that way. Obesity is a way to keep padding the body out, putting the world at bay. The world is still touching my skin, but now through some alchemy of inaction and donuts, the skin is more distant from the heart, the liver, the bones, the womb, the stomach. It's out there, and I'm in here, a little further away. The drugs keep the world at bay. The food keeps the world at bay. The inflammation keeps the world at bay. The delusion of living in a safe, respectable place keeps the world at bay. The gun keeps the world at bay. I wonder about this Mr. Roof, 5'9" and 120lbs. He is the opposite of padded, and yet he is the current focus of expanding grief, hatred and concern. He has expanded into the minds of the whole nation; his expansion has been so radical as to obliterate nine people in its wake. The Confederate flag expands over the Capitol in Charleston, even as the US flag is at half mast. A delusion can't be flown at half-mast: if it begins to come down, it falls apart. An expanding sense of wanting to isolate hate, but that is obviously nonsense, Hatred lives everywhere. Intolerance lives everywhere. The words unspool and expand across the page. My breath expanding and releasing. Larissa and Sam, breathing and writing. Steadying my feet on this tightrope of words. Allowing body and mind to expand in that other way: the way that accepts contact and grows to meet it. The way that says, Oh, what the hell. What do I think I have to gain, keeping myself from touch? If it's here, I'm already touching it. If I'm already touching it, it's already OK. Breath expanding to distress, contracting to this new way of sitting with the breath and the body. Body-mind expanding-contracting with the breath. It's all here, all now. Yesterday I went into the West Lebanon Feed and Seed looking for something to distract and comfort Chloe, which really means - to distract and comfort me. Outside were the remaining tomato and eggplant starts - the tomatoes mildewy with strain of expanding roots in too-small pots. The eggplant were OK. All buy one get one free. I could stand and think, Beings are numberless, I vow to free them all, but I could not make myself buy one get one plague-bearing plant, and I did not say, This is absurd. Give me your orphans, already. In the distractions and fetishes aisle, it was no better. A $25 fox toy? Really? A pink fluffy bunny with white ears? I could not. I could not. I kept feeling my mind expanding outward to the woman at the hospital who could not afford $25/session for fibromyalgia physical therapy. I walked out. No bunny, no tomatoes with mildew, nothing to pad my sad self from the world. Then this morning, Timothy came home with a brown paper sack tied with yellow and blue curled ribbons, and it was a gnaw-rope with bones, from our friends John and Sunny, sending their best wishes. A boney gnaw-rope for Chloe, and I felt my heart expand. This was why I could not seal the deal, yesterday. I wanted someone else to be offering the kindness I needed. I wanted to let go of choosing and taste and shopping, and just get the hell home to where my undistracted distracted friend was laying, trying to remember not to bite herself. Expanding like this says: it's not up to me to control my way through this situation. Sometimes I will come home so exhausted from sleeping nights on the couch near my dog, in range of her Very Large Array, that I will feel like all joy has died forever, and in that case it does not make any sense to do anything but go to bed and sleep it off, where a dream will come, in which my bald preceptor will appear, kindly asking if my circus performance will be this small boy burrowing through the ground for 417 minutes, hours, days, or years - and I will realize, yes - that IS the trick I've been preparing with such feverish intensity, welcoming people into the big tent, even as Mole Boy gets busy in the earth. He says it kindly. The boy is ready. All I'm doing at this point is hosting the whole thing, ready for the burrowing to begin. I expand to a sense of knowing that the digging I saw in another dream, just before hiring Chloe as a lunatic companion, is proceeding apace.

We are digging. To where? And why? That is too many questions. I want to spend more time expanding into full experience, and less time contracting into email, syllabi, tiny jobs that act as their own form of inflammation and keeping the world at bay. I want to spend more time on the icy couch, expanding my skin onto it, warming my way through the block of ice I was born to, and less time blaming others for not providing me with a comfier resting place. I want to be less of a brat. There's a call to expansion in me right now - a sense that I should take my summer teaching money and convert it into training, certification. Taking what's Caesar's to learn to speak Caesarese a little better, to wrangle my way into the hospital rooms and prisons and schools where the action is. My teaching money - as though it already exists, which it does not. The old, expanding restlessness is back - the one that sees a high, flat, volcanic plateau in Flores with witch-hat mushroom-cap huts and thinks, Yes. Take me from this world of email and out into the ever-expanding world of distance. Distance is a padding. Not-distance is a padding. I want to be a stranger for awhile, to travel alone again with skinny bones and a fat pack at my back. To tower and lurk and flit, away from anyone who knows me. But this leg needs home to heal, and these malcontent urges are not grounded. Keep digging, boy. The tunnel expands behind you even as the unknown opening at the end of your travails grows closer. Where will you come out? No one knows. Not you, not me, not all the people in the tent. But after 417 somethings, there you will be , having crossed the whole distance with your body's work. You'll be in the kitchen again, eating a sweet potato. Or in your bed, sleeping off the pre-storm death of a summer's afternoon. You'll come out standing, to recognize with expanding clarity that absolutely everything you need has been here all along, if in disguise. It'll be OK to drop the gun, the food, the keys, the shovel, the drugs, the delusions, and you'll just be right here. You'll be right here whether or not the interview works out, whether or not you go on that retreat, whether your dog runs like the wind, or hops like a three-legged bunny for the rest of her life. You are there. You are here. Wherever you are, your heart of delusion and clarity is there also, expanding and contracting, breathing in, breathing out, Now and Now and Now and Now. Today was my second attempt at making a presentation on Mindfulness to a group of fibromyalgia patients. It's not actually the easiest project in the world, talking with people who are in intense pain about how they could improve their relationship with suffering, especially if they've traveled far & come to sit in stiff conference room chairs on a beautiful afternoon in June. Still, it's definitely worth trying, and I'm getting better at it. If undertaken consistently over a period of time, with good support – simple mindfulness practice can help with the chronic pain of fibromyalgia. This help is different from the assistance pain medication can offer, because it employs your own resources of body, heart, breath, and mind to work directly with your felt experience of pain, your relationship with pain, rather than focusing on eradicating the physical symptoms themselves. The cultivation of mindfulness attunes you to what is strong, sane, compassionate and wise within yourself, no matter how difficult your situation may seem. Mindfulness practice can help you grow in a sense of your own resilience in the face of pain. As you become more familiar with your own embodied sense of well-being, and as you cultivate your ability to bring that well-being to the forefront, it is as though the container of your awareness grows larger. [True confession: no Giant Slurpee of Compassion was deployed in the making of this presentation. Still, I am a big fan of architectural-scale junk food, and the point about the container still stands.] Exercises: Today I took my post-surgical self out on the town. The plan was to fill out some paperwork for summer teaching, and then go to the eye doctor for a checkup. The reality was: steady pouring rain. Even though I spend a lot of time cultivating the sense that I am going to be OK and nothing is unsurmountable, I was aware of: no change for the meter, no umbrella, and three flights of stairs to the bureaucracy-office. Hmm. The car in front of me pulled out just as I was floundering my parallel parking job, and it turned out the driver had left 25 minutes on the meter. Sweet. The stairs were no real problem. I finished the forms just in time to scoot away for my appointment & as I exited the building, back out into the rain, I startled a small woman in a hooded raincoat, standing right behind the door & looking very much affronted by the world. I apologized lavishly. Why not?

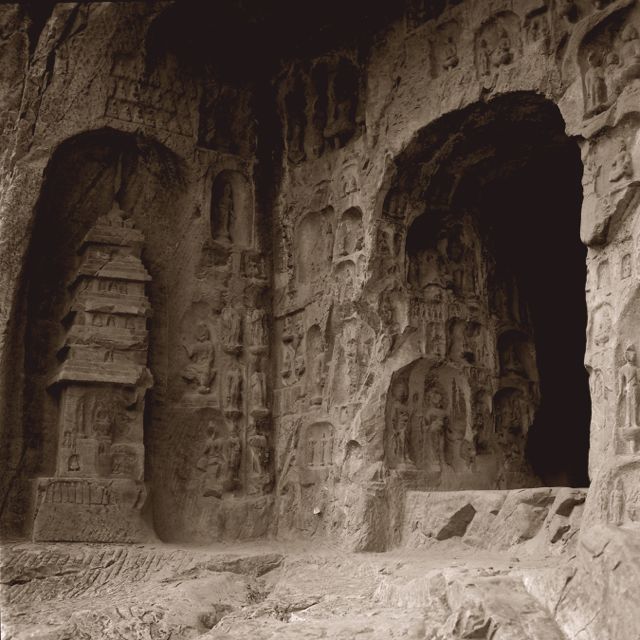

Again, in front of the optometrist's office, a car pulled out just as I needed a space, but this time - no luck with the meter. I thought about just sticking a couple of dollars under the wiper & then realized the new pirate-meters in town have credit card slots. Still in the pouring rain, I tried to swipe my card, first one way, ineffectually, and then the other. It stuck fast! No budging it. Hobbling drippily into the office, I told the receptionist that I was there for an appointment, but needed to take care of my meter woes. Can I borrow your scissors to try to get my card out? Smiling, she said, No, there's a better tool right over there. And you're going to need an umbrella. Here. I'll come with you. You won't be able to hold the tool and the umbrella at the same time. The outside halves of each of us got pretty wet, but it didn't matter so much, because I was delighted to have this kind stranger's company in the rain, and she was delighted to help me out. The credit card came right out of the slot using her perfect flat-pronged pliers; then, I turned it around, and it swiped right through. Our short walk under a too-small umbrella converted my simple de-fubaring mission into an experience of being welcomed back to the family of humanity. She told me she'd gotten rained on earlier in the day, and I felt less foolish. It was sublime, but it wasn't efficient. Efficient would have been: the credit card works the first time, or if not that, I pull it out myself, or if not that, the receptionist sends me back out in the rain alone, while she fires off some emails. Efficient would have solved the problem, but it wouldn't have healed my heart. Efficient would have seen my floundering as a proof of weakness, and averted its gaze. Instead, I felt looked upon kindly by the world. Later, eyes dilated and watering, I listened to the old man in the store when he said the bright-red frames looked nice on me, and ordered new glasses. May they help me to see kindly, if sometimes inefficiently, in the months to come. Just lately I've had several conversations about ambition: what it is, whether or not the various people I'm speaking with have it, whether I have it. I don't know about you, but in the circles I lope (or, currently, limp) in, ambition is pretty uncool. It's not done. Or if it's done, it's practiced out of sight, like the friends I had in college who turned out to be graduating summa cum laude, even though the whole four years, I swear they seemed way less nerdy and preoccupied with their work than I did, and in the end I had scattershot grades that averaged out to basically OK, but let's not make a big fuss about it. While I will happily tool around at the bottom end of various socioeconomic scales (income, institutional achievement), I am ambitious about waking up. There's an Anne Lamott story I love: she's out with a dying friend, shopping to please some mean boyfriend who's into slutty clothes. She comes out of the dressing room in this tight purple woo-woo dress, and asks her friend whether it makes her butt look big. Her friend says, You don't have that kind of time, Annie. I love that. That's the kind of ambition I want to keep coming back to, because it says there are definitely worthwhile things that we can do with our lives. There are also a lot of pointless distracting things that lead nowhere, and it is important to cultivate the former and let go of the latter. Which all sounds clear and decisive, but in practice is complex. Take right now, for instance. I am sitting on the kitchen floor, eating my friend Margery's spicy cashews from the jar, writing with my laptop toasting my upper thighs, while Chloe-the-dog hyperventilates gently, trying to remember not to bite the fuck out of her leg. I am not feeling especially stern about sorting out the waste-of-time components of this situation from the wholesome ones, though I'm pretty sure ceasing and desisting on the cashews soon would be smart. Here is an example of persistence: over centuries, countless pilgrims chipped 100,000 Buddhas and bodhisattvas into rock at the Longmen Caves in China. (I visited the caves & carvings on my 24th birthday, traveling solo overland from Hong Kong to Switzerland, and they are still one of my favorite places on earth.) Is 3D Buddha wallpaper ambitious? The sculptures range from 1 inch to 57 feet high, so I guess it varies is a reasonable response, but who knows? is even better. You can eat cashews with a heart of pure gratitude. You can carve Buddhas feeling like, that guy over there is doing it all wrong, and when can I quit with this chip-chip-chipping already, and eat cashews?

So it's good to ask again and again during the course of a day, what am I doing, here? In the monastery, we used to chant, the days and nights are relentlessly passing, how well am I spending my time? And what do I mean by well, these days? Profitably? Kindly? Enjoyably? With an eye to liberation? In this moment, what action, speech or thought would be in line with kindness? That is a kind of ambition I want to keep cultivating. In the space of one week, both my dog & I have had surgery on our right knees. Hers - a TPLO for a torn ligament - is much more serious than mine - an arthroscopy for a torn meniscus. Chloe's procedure involved a long incision, a controlled fracture, a metal implant, & multilayer sets of stitches. Mine was a stitch-free three-hole Cousteau affair, using the microscopic 2015 equivalent of la suçeuse to extract the offending bit of gristle with minimum fuss. Now, I'm mostly comfortable, while Chloe is racked with pain, anxiety and desire to bite the fuck out of her knee. Here's this morning: Chloe went to town last night, destroying stitches & staples, despite Cone of Negotiated Non-Licking. Mid-night terror, new 3AM hospitalization, whole new set of stitches, new Very Large Array version of the Cone. It is hard being a dog. It is hard loving a dog. She is resting & I am finding my way to my feet like an old new colt. And here are two extremely helpful things my friends Larissa and Annie posted back: Sorry your pup is wearing her Hell Toupee! It IS so hard loving a dog, or anyone who is suffering..... So, yes: Chloe IS wearing her Hell Toupee. We have gone through three rounds of bigger and bigger Toupees, because everything we have tried has failed. At this point, her headgear is picking up messages from outside the Solar System, which she translates into high-pitched whines and growly snores, to the intergalactic enlightenment of no one. Yes: it IS hard loving anyone who is suffering - basically everyone, including myself. I don't have any children: no right-path-treading children, no heroin-addicted children, no children in jail, no children in medical school. But I DO have this furry being in my life taking on the role of Child Understudy, and right now, loving her is hard. A few days ago, after the first trip to the emergency hospital, when new staples had gone into Chloe's leg to replace the first round of stitches, and we were feeling pretty giddy with relief, we took a joyride up and down the streets around our neighborhood. Chloe stuck her head out the window in Toupee 2.0 , tongue flippy-flapping, and I dubbed our ride the March of Folly Victory Tour. Right on cue, a lady in a white minivan just pretty much stopped right there in front of us at an intersection, and quit driving. The little boy biking nearby executed some loopy maneuver of his own. I realized we were all in this together, flailing and winging it.

Today is more like the March of Folly Survivors' Hall. My mother & husband are dead-beat from their expedition to the hospital in the middle of the night (I stayed home, crutchily). My husband's back is killing him from hefting Chloe like St Christopher and the Good Shepherd rolled into one. My mother's hip hurts. Chloe is zonked from her new pain-killers and the trauma of re-opening the wound in her leg & having it re-sewn. I, helpfully, am adding stir-craziness, reflexive mother-daughter dynamics, and post-surgical paranoia (is it supposed to feel like this?) to the mix. Last night, I could feel a moment when I honestly wanted to lose it, but I found I couldn't, which was interesting. I was gearing up for a big old self-pity, dog-pity cry-stravaganza, but what came out instead was blessing chants and the Fire Sermon. I heard my friend Sid's voice asking what's the benefit? - and since I couldn't actually see the benefit of wailing, the March of Folly Victory Soundtrack arose instead. I don't know how this resolves. Chloe's nuts right now, weaker physically and even more maddened by the new-new Toupee than she ever was by the previous ones. Did we do the right thing, following numerous vets' recommendations and getting her an expensive & complicated surgery, in the belief that she would suffer less as a result? Who knows? It's not within our control. We'll keep taking wobbly steps in the direction of what seems good & true & beautiful, and there will be blood and pee along the way, but we'll be in this together. Pray for us, and we'll pray for you. Dear Rachel, Hope this finds you well. I am in Massachusetts, at the home of a woman who makes fur garments out of roadkill animals. Her little daughter, Naia, lives here too, and likes to launch herself from the top of the hammock down onto any unsuspecting guests who may be laying in its depths. Not very far away is a whole sprawling mess of exurban greed, but here, mostly, I hear birds, with low traffic roar only in the distance. There’s a teepee, with old walnut trees nearby, between whose trunks the hammock is slung. We are here because our beloved mutt, Chloe, is getting knee surgery nearby, and needs to be in hospital for a few days. Then, when we get home, it will be my turn under the knife. Before, I did not understand what you were going through, but now, though the lens of my own pain, I do. My handwriting has been a source of consternation to many. Imagine that same script, written on random greasy found scraps of croissant bags, in leaky fountain pen… now I am typing. Rejoice! You have very legible writing, careful and particular, with a wide variety of o’s: forward, backward, whole, and implied. You ask some really good questions. You say, everything that happens, happens in an orderly, compassionate universe. How can the universe be orderly, compassionate? What do you mean by universe? I’m so glad you asked those two questions together. When I was about your age, I was staying at Thich Nhat Hahn’s monastery in France. I had been practicing meditation intensively for about 7 months, and was fasting with a small group of people who were staying on to help with a big retreat that was coming up. In exchange, we got food and lodging, and were invited to take part in the retreat. The evening after we broke fast, I was sitting with the community for evening meditation when suddenly everything broke open & I saw that this body & breath & mind were no other than the body, breath & mind of the entire universe. Time, space, separation, inside, outside all fused together into one intensely beautiful, loving, aware, and connected sense of Being. I saw that what people call God is inside of everything and at the same time utterly beyond what we usually tend to imagine the world and ourselves to be. I saw this was not a truth about me as some special being, but a truth about Being itself and all beings. Over time I have come to see that initial, overwhelming vision manifest in the “ordinary” workings of day-to-day life. If I listen deeply enough into each situation as it presents itself, there is always a way in which it proceeds from a central space of sacredness. There is always a way in which I can speak / think / do / be coming from that place. When Jesus says, the Kingdom of God is with us, and it is within us, I think this is what he means. I agree. Permaculture, and making beautiful fur hats from animals killed needlessly, and composting, and being creatively frugal, are all expressions of this one basic truth: the sacred and the ordinary are one. Do you believe each person is unique, not reincarnated? If you believe in reincarnation, why? I believe each person is unique AND reincarnated, and each life we live is an opportunity to become more & more compassionate and awake. The whole world is a school and a school bus. When we don’t understand something – what it might be like to live with a certain physical limitation, or to be greedy and power-hungry – BAM! Life presents us with an opportunity to experience those things firsthand. We then have a choice: glom blindly onto the situation as me, my, & mine, or be mindful of what is happening. What is this like? What am I feeling? Does this remind me of anything? Where is suffering arising in this? Where can I let go? What might be skillful here, if I’m not primarily concerned with armoring myself, or grabbing what I can, or running away? And I think this learning process is so immense that it takes us literally thousands and thousands of lifetimes even to get to the point of feeling secure enough, informed enough to begin thinking about waking up. Nothing is wasted. The lives I spent as a tree, as a crazy weasel, as a slave, as a slave-driver, taught me compassion and made it impossible for me to get all sniffy when Rick Perry is being an idiot (again). Compassion doesn’t mean I am not going to fight hard to make sure he doesn’t come to power, but it does mean I can’t act all righteous: well I would never… Bullshit. X lifetimes ago, when I was Rick Perry, I did exactly the same things. Thich Nhat Hahn used to tell us: this is like this because that is like that; that is like that because this is like this. We are all in this together. Why follow one religion, when the “good” is to express kindness, and not to convert the world to one’s personal beliefs?

Well, in short, because there’s a lot of work to be done, and if someone’s already invented a set of tools that prove themselves effective to do that work, I’m going to use them, rather than trying to reinvent them from scratch. People like Jesus and the Buddha show up here from a very evolved consciousness that chooses from compassion to come help us out. What we then choose to do with those teachings when we turn them into organized religions is a famously mixed bag. Sorry tales of religion gone wrong – though useful as warnings – needn’t become impediments. The Buddha’s core teachings, to me, are like the shovel, clippers, wheelbarrow, saw, axe, and twine I can pick up and get to work with. They are the handbook that tells me a garden is a possible outcome (when I am standing in a thicket), helps me identify dangers and successes, suggests possible plants to cultivate and to avoid, and gives me confidence to keep going even when some crops fail and others come out completely unexpectedly. It is my responsibility to tend and cultivate my patch of land. Shovel-worship’s not going to do that. Mistrusting shovels isn’t going to do that. Reading the handbook over and over while agonizing over what kind of garden I might like to try to grow someday isn’t going to do that. It’s easy either to mistrust all religion, or to want someone else to tell us what’s good and bad, but neither of those approaches yields good results. In the first case, we deprive ourselves of tools. In the second case, we deprive ourselves of power, and we abdicate from our responsibility as chief gardener of our own lives. If we're lucky, we have good teachers to mirror back what they see of our efforts, and to show us tools we might not have known about, for new tasks we are becoming aware of as we get on with the work. I teach meditation now, and Buddhist practice, not from a point of view of conversion, but from a sense of making tools available to people to help make sense of their lives. It’s definitely not for everyone. People come and go as they wish. Teaching is: Try this one & see if it works for you. If it doesn’t, tell me why. You may need a different tool, or a different teacher. If it does work, tell me how. What tools do you know about that I may not? Teaching requires me to keep learning, so that I can offer something alive and interesting, something that's making me grow, so that I can be growing alongside others. There’s always much more. What do you mean about how trusting ourselves takes practice, purification, and faith? what does practice mean, or entail, or do? What is purification and how does it happen and why is it necessary? Practice, on one level, is setting aside some time every day to develop a relationship with Being itself. Without that, especially in this culture, it is easy to get swept away by doing & by small ideas of who and what we are. On another level, practice is deciding that every aspect of your life is something you are willing to be interested in. In Buddhist terms, that all-encompassing attention is the Eightfold Path. On yet another level, practice is recognizing that we often need to do things mindlessly many times, before we even begin to notice them, and that as we notice them, they take on a certain transparency. We notice with more wisdom: Yes, this is worth doing. Or: No, this does me & everyone else no good. We abandon what does not serve waking up. We are careful not to pick up new bad habits. We try to pick up new good habits. The good habits we do have, we take care of and nourish. That’s purification – and the results of it are that we feel happier, clearer, more confident in our ability to approach life with wisdom and good heart. We aren’t worried we are going to fail, because we see that everything is workable – and even valuable – if we take it moment by moment, with interest and awareness. Does the question what is the point of living ever go away? When I was younger, I felt much more anxious that I might miss something big, and wind up in some backwater, away from the current of what my life was supposed to be. Now I see life is much more resourceful than that, and also much less of an external event. It wells up. It flows. Situations arise, offer themselves, change, and end. There is a Jewish song that says: All of the world is just one narrow bridge which we must cross, and above all is not to fear. Wherever we are, we are on that bridge, and our hearts are there to open. Studio practice, movement practice, meditation practice, teaching, taking care of friendships and family relationships, living, as you say in the best way yet seems enough. I wonder What is the right thing to do here? Is this worth pursuing? What’s the benefit of this? What am I afraid of here? What is this person thinking? What goes on here? There’s also a sense of resting in things as they are, and of things revealing themselves clearly. Oh! That begonia over there is glowing flame-red. It’s enough. People are so interesting. I have work to do. My dog’s leg is in a purple bandage & hopefully she will be able to walk and run soon. It’s enough. I am grateful. I hope some of this is useful to you. I love hearing from you & it’s been very useful and enjoyable for me to write this letter. My sense is that you are living very well indeed, to be sticking with questions like these. Keep asking, keep feeling deeply into the answers and questions you find in your body, heart, and mind. Back in North Carolina after your travels, I hope your crops are doing well. I wish you thriving of all kinds. Love, Julie What if suffering were a collectively held resource, like the world’s forests and oceans, and our work as humans were to take compassionate responsibility for the portions of suffering that come within our sphere of influence? What would it mean to take good care of suffering? Inspired by Nature Conservancy stories of conscientious landowners doing their part to preserve and to rehabilitate their bits of the landscape – I have been feeling into my role as a stakeholder in what I have come to call the Suffering Conservancy. To be clear, the Suffering Conservancy is not about perpetuating pain – old human patterns of ignorance and reactivity do that very efficiently already. It’s also not about pretending I can eliminate pain like some kind of virus or invasive plant. Instead, there’s a hunch that each arising instance of pain – received with openness and compassion – is a gateway to understanding the fullness of human experience. This hunch feels aligned with the life-science realization that a small section of woods can be a gateway to understanding a whole forest. It also resonates with the Mahayana Buddhist idea of Indra’s Net: Far away in the heavenly abode of the great god Indra, there is a wonderful net which has been hung by some cunning artificer in such a manner that it stretches out infinitely in all directions. In accordance with the extravagant tastes of deities, the artificer has hung a single glittering jewel in each "eye" of the net, and since the net itself is infinite in dimension, the jewels are infinite in number. There hang the jewels, glittering "like" stars in the first magnitude, a wonderful sight to behold. If we now arbitrarily select one of these jewels for inspection and look closely at it, we will discover that in its polished surface there are reflected all the other jewels in the net, infinite in number. Not only that, but each of the jewels reflected in this one jewel is also reflecting all the other jewels, so that there is an infinite reflecting process occurring. *** Let me be a little more concrete. Today, our friend John died, as a result of a lightning-bolt recurrence of cancer. We went to see him three weeks ago, when he had just received his new diagnosis, and he said, “I could be dead in three weeks, or I could live another three years.” As it turns out, the first was true. John did not want to die. He was very clear about this. He loved life, and was good at living it. He was clear about the fact that he would not allow his illness to define him. Between the first round of catastrophic cancer and the second, he lived well and fully, reveling in the mountains and forests he loved, and in the wide circle of his friendships. That first week, back in the hospital, we talked about his coming to stay with us for a little while after discharge, as a break from the small art studio he had been living and working in for years. We talked casually, with the climbing bum’s familiar back-knowledge of an endless chain of give and take. He was glad to know we had a shower downstairs that he could use. We were glad to think we might have a tree-sprite housemate for a little while. Then it became clear: casual housemates weren’t what John was going to be needing at all. He was going to be needing a place to receive hospice care, to prepare to die, to be watched over by friends and family. We were up for this in theory. I stood in the living room and visualized the dissolution of its familiar order: no more couch, carpet, table, chairs. Instead: hospital bed, drip, urinal. Dying friend. Fine. What else would we be doing? It didn’t happen that way. Before we could risk making our helpfulness into a nuisance, John showed us he needed to be where he was, in the public space of the hospital, and not in the private space of a house. He would die well under the care of doctors and nurses – some of whom I knew personally from a recent stint as a hospital chaplain intern. His family and many friends could come and go according to a schedule that would not be cramped by a parallel household’s needs for privacy and rest. John took good care of his suffering. Previously a voluble, expressive man, he became quiet, in order to tend more closely to his experience. When we came to visit, he would ask us to be still, sit by his side, and hold his hand. At some level this might have seemed like taking care of John, but I think we also came away with the realization that he was taking care of us by offering the example of being with his suffering. Listen. What’s the benefit of these thoughts? These actions? Are they fitting for the bedside of a man who’s aged three decades in three weeks? Am I opening a clear space for suffering, giving it space to pass through, or am I cluttering its surface? *** This morning we dropped off our beloved Chow-Chow mutt for surgery. Because we spent extra time in a big human-dog-pile on the Airbnb bed (special dispensation), and then got screwed in Massachusetts morning traffic, I didn’t get to my morning sit until after we’d handed Chloe over to a sweet veterinary student at the hospital. I limped to the lawn outside, and sat down on one of many big wooden benches dedicated by grieving families to their deceased pets. Closing my eyes, I felt into What Is. Sitting on that dog memorial bench, one day after losing a friend to cancer, one week before my own surgery, as my own sweet beast was being prepped for a scary knee implant, outside a building full of sick or injured pets & worried people, I found that What Is, was sadness. I felt it well up in my chest and eyes, and then I saw all the suffering of this particular place all around me, opening up into all the suffering of sick people and animals, whatever their outcomes might prove to be. I saw untended pain, pain well tended, chronic pain, accidental pain, mortal pain, and pain of recovery. It was all right there, breaking my heart open. I kept parts of my attention grounded in body-sensations, in- and out-breaths, and the sounds of the birds in the trees above. The pain built to immense proportions, and all the while, there was room for it in the space of an open heart. It would ease, then John’s face or Chloe’s face would come back to me, the tears would flow again, and I’d see all the others. Gradually, just like that, the whole tide passed through, and I found I was looking at a little robin hopping around in the grass about twenty feet away from me. I felt alive, connected, and clear as I chanted vows: Beings are numberless, I vow to free them all. Then, noticing the robin was gone, or maybe now part of a pair, I rose tear-streaked & refreshed to meet my husband in the waiting room full of hobbly, coughing beasts and their devoted people. In my experience, each time I agree to feel pain fully, to feel pain that’s not strictly “my own” I emerge with this very sense of aliveness and clarity. And I think that is precisely because suffering IS a resource we hold in common, and it holds us. Negotiating to feel only this little bit of pain, or that one, for as little time as possible, while keeping all the rest at bay, is as unsatisfying as trying to swim in the ocean while keeping most of yourself dry. You might emerge with your hairdo intact, but you’ll never know the pure joy of rolling through the waves. You’ll never feel the ocean embracing you & everyone as its own beloved children, and you’ll never step back onto land reborn, unborn, salty, sandy, and grinning from ear to ear.

Here is a good invitation:

We have been sitting in silence for ten days straight. The person I thought I had the hots for was (surprise!) unstable and tragic enough that he left before dinner on day two. Would you like to spend a couple of days with me here in this little retreat center, learning how to use a pickaxe and having actual conversations, before we decide on anything more drastic? Yes. Yes, I would like that. This is the first time in my short life that I am away from my family for Christmas, and so, yes, spending time digging big holes and mending things here with you and some other quiet people would be nice. Here's another one: Having dug holes with you for a few days, I realize I am glad the other, tragic one left, and it is you I am spending time with. A few years ago, I walked all the way around an island, and that was pretty wonderful. I notice we are on an island. Would you like to walk around it with me? Yes. Yes, I would like that. I have been a monk for the last three years, and have come to realize that that life is doing violence to the tenderest parts of myself. I am still in love with the beauty of shaved heads & alms round, of living in the jungle and being quiet, but I know my heart is withering, and so here I am. Let's walk around this island together. Will you teach me that song? The one that goes, All of the world is just one narrow bridge, which we must cross, and above all is not to fear? Yes, as the water laps up onto this dark beach, I will teach you. Also, here's another one: My very life is sustained throughout the gifts of others. That is a good invitation. Will you let me get closer to you? Will you let me unmonk you into the world? I would like to invite you to complete the work you've begun, by dismantling it. I invite you, dogs, to stop nipping at my legs. I invite you, nuns, to call your dogs off. Dogs, we invite you to cut it out. This one's no trouble. Tall, hairy lady, we invite you to come inside and eat pink crumbly biscuits while we apply bandaids to your leg. We are sorry, but our dogs do a good job deflecting wrong invitations people may feel from our small cluster of women's huts. Widows' huts. We shave our heads, but we aren't nuns. Please come sit with me in this circle of stones under the rubber trees, under the bodhi trees, in this holy forest where nothing is holier than in any other forest. Please bring your bandaged leg. Please let's sit here together as we fly apart. Please let's give one another the blessing of leaving our lives exactly backwards from what they were: you leaving where I will go; I going to what you have left. Later, when I am a nun, you will invite me to leave the monastery, saying my being there is a crime against the heart. But I won't. I need to be a criminal for awhile. I need to keep doing this violent discipline, getting up in my cold, smoky hut, hauling barrows full of rocks, starving and dreaming, for awhile. And you need to find your own way back, failing into greatheartedness over lifetimes. Tissaro, you were. There was another Tissaro, a French one. I stayed in a borrowed flat in Clapham with him one night - he was disrobing and I was only going deeper into it all. But you were the one who accepted my invitation to go around the island, and I was the one you invited to learn: All that is mine, beloved, and pleasing, will become otherwise, will become separated from me. You were. I was. I am glad we both knew when to accept, and when to decline. *** We were still together that New Year's Eve, and he invited us to come with him up a river, up a waterfall, to a place where a couple farmed cashews, for lunch. It was an amazing meal, a place that scarcely bore believing. How do you run a restaurant in the middle of the jungle, with no path and no signs? Actually, I felt the invitation was to you, and I was an accessory to the fact. You and he talked about Thai toilets, with their water-scoops; and Western toilets - "nothing but a smear-job." I still think of this twenty years later, reaching for the toilet paper. I felt like an accessory to the invitation because that is a lot of what I'd known from the world. The child as an afterthought to the parent. The woman as an afterthought to the man. The individual, to the family. It was a bad habit. Invitations, I now know, should be to a particular person, issued and accepted clearly enough that a person knows what her choice really means. I felt he saw what I saw - how pretty your face was, behind the grief - but he had a better claim, being also a man. How gay was the monastery? It was mostly straight-gay, I'll bet - that kind where what you really mean is Stay with me, but what you say is This is the way of the Noble Ones. I want to be able to say Stay with me, not, Here is what we do. I think I can say it. I think I say, Come to this room, and write. You give me courage. I may still turn to dogs when I can't say what's too raw, but your presence, your writing, is an invitation to be brave. |

|

108 Names of Now

RSS Feed

RSS Feed