|

Sam and I sit under the trees in the park where the two rivers meet, and eat Syrian apricot cookies cast in Chinese mooncake molds. Adrian and I walk along the Baltimore inner harbor, past stacks of burnt-out plaster molds, from some mysterious foundry project unfolding in the swanky warehouse lofts nearby. Have they been producing artisanal garbage cans? Garbage cans are the only objects nearby of roughly the right size and shape. Education and religion are molds, and ideally their molding is a process in which the student or disciple adopts a chosen form and takes it on wholeheartedly. If entered into completely, the training form displaces other possible addictions and patterns, other ways of getting embroiled. The student applies herself to learning the shape of the mold and inhabiting it with her being. She is pressing life into a training pattern established by others who (hopefully) see both its usefulness and its limitations. Through study, she learns the mold's contours: which parts of her being are glad for its shelter, and which, obviously, yearn for a different shape altogether. She learns about resistance-energy, about the rewards of accepting a community's mold, and the costs. She begins to develop insight into being itself: the primordial nature that is not a mold & is not a being-molded. It is awareness itself, the awakening energy at the core of all that is, the matrix of all our patterns. Seeing this, she knows mastery of her chosen form, and, transcending it, realizes the formless. Ryushin Sensei grew in the mold of western science - a pediatrician and psychiatrist - and trained in the mold of Zen - the Mountains and Rivers Order. When I met him, he was Abbotting - teaching brilliant Dharma talks at Zen Mountain Monastery, residing with his nun-wife, Hojin, hosting genially at the meal tables in the great hall of the stone house in the forest. He was kind, amused by Elana and I, on retreat together, hilarious together, and he wanted to know what we were doing. Elana fed him cookies - a much better answer than my stiff lineage-talk. Just lately, it seems Ryushin has been either breaking or going more deeply into his molds. Darkly muttered Shamanic Interests. Deeply condemned Extramarital Affair. Bad-boy confession, six-month exile, reproof. All of it very Somebody. I am reminded of the end of the Earthsea Trilogy. Ged has gone into the dark to restore the integrity of the border between life and death. He's come back with the Rune of Peace, revealed his young fellow-traveler to be the long-awaited King, and arrived on the back of a great dragon. There's to be a feast for him with songs and more, but instead, Ged gets back on the dragon, his friend, and flies away to his obscure island home. He has done with doing, someone says. That seems the way. Stepping down, stepping out, letting go of Sensei, and going out into life unfixed by any mold. Much later, when Ursula Le Guin returns to Ged in her writing, she makes him a moody goatherd. All his magic is gone, and so he is ready for an open life, a life with room for the ordinary-extraordinary roots of love. May it be so for Ryushin, as for us all. Wei wu wei. Doing not-doing means acknowledging that the molds have never really fit, and the desire to force a match is gone. No more sliced-off toes, no more sliced-off heel, no more glass slipper, no more Princess. Margery says, Kung fu means mastery. It means whatever you are doing, you do it with full presence. It's transferable, and, in the style of many-armed Kuan Yin, it's adaptable. Why harden around identifying with one way of being, when the next situation will require another? Much better to develop the ability to fill any mold with skill and discipline, and then to set it aside gratefully, as soon as its usefulness is done. Not a tai chi expert, or a meditation expert. Not a painting expert, or a cooking expert. Just being, skillfully. This goes against the logic of the world, because constantly embodying & moving on leaves little trace. How will I be recognized? How will I be praised? Maybe not at all. Maybe it will all seem squandered. Maybe Most Horrible, I will never give a TED Talk.

But, when I sit down in the second row of the Baltimore-Boston flight and realize that I've somehow joined the Unaccompanied Minors' Club, I know what to do. Open. Let go of other plans and preoccupations, and listen to two 12-year-olds' stories about water parks and grandmothers. Use their sharpies to draw a cheetah & a birthday cake. When the boy by the window says he is "dark" and likes to draw "dislocated" people, ask him if that is because something very painful is happening in his life. When he says, My mom, wait a bit and ask if she's sick. When he says, She used to beat me, and that's why I'm going to live with my grandma, and that's why I like to draw her, dislocated, tell him there's nothing wrong with him. Tell him he's a great kid. Tell him he'll find other ways of working with his pain, besides more pain, and anger. Listen to Katy Perry's Roar together, and, descending through the clouds, add red Jordans to the cheetah. As for the little girl, listen to her love for her Nana, and admire the Febreze-scented Pooh-Bear doll that takes up 2/3 of her carry-on luggage. Agree, definitely, that her older sister, Madison, is nicknamed May-dog, and NOT Maddie. Listen to the lore of her hamster, Thor, with his long blond hair, and, lo, the lore of the hamsters who came before him. The boys says, We will meet again, and I will be 10 feet tall, and you will have white hair, and I will be your favorite student. Yes, why not, may it be so. Her stylish Nana is waiting, with her good haircut. His aged Grandma is waiting, an oxygen tube in her delicate nose. They cry together, molded into an embrace of love and relief. Hang in there, old lady! This kid will need refuge for a long time. Not the mother-mold, and not the not-mother-mold. The endless, shifting shapes of presence, response, creation. I wouldn't trade this dance for anything.

0 Comments

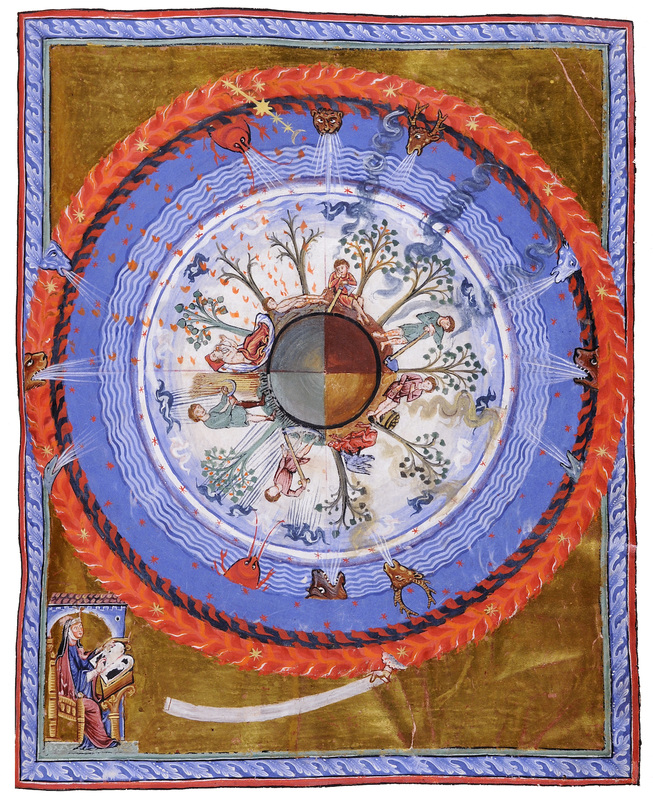

At the beginning of the session, while my guides & I were looking at a book of mandala images, mostly from nature, I noticed in particular an image of one of Hildegard of Bingen’s illuminations. It is the four seasons, I think. Large animal figures are blowing the winds in towards the world, from the four directions, and maybe angels are turning the keys that move the world. In the bottom left corner is a tiny alcove, in which sits Hildegard, in her nun’s wimple, recording this vision in a book, using a quill pen. Seeing this illumination at that juncture was auspicious: it reminded me, throughout the session, of the possibility of being fully within whatever was arising, while also grounded in this body & mind. It reminded me that at any time, I could reframe my experience, and go back to the alcove (the body, the mind). It reminded me that whatever was about to happen, Hildegard & others like her had probably been there before – I have had this sense with other experiences – and I was in good hands. As my experiences began to shift and deepen at the beginning of the session, I had an intuitive sense of, Oh, this! I know this! Sort of like a homecoming. There was nothing in it I felt I needed to resist, and in fact I knew that the less I resisted, the better things would go. This might sound odd, but a previous place I had felt this sense of informed and wholehearted consent was in getting my wisdom teeth yanked a couple of years ago. I liked the dentist, and I trusted him. When he started on the first tooth with the pliers, and the enamel started making shattering sounds, there was a moment of real fear. But then I thought, You have come here to let this man take your teeth. Let go! And the first tooth came flying out. The second one took a little more doing, but soon enough, it was out, too, and both of us were delighted to see it, gnarly & slick with blood, as its sister had been. He had freed me of teeth that were no longer serving me well, and I had worked willingly with him to make this possible.

Let this be for the good of all came up as I passed from one state into the next. I could feel I had no expectation of what ought to happen, or what I wanted to happen, and I could feel the commitment to allow this for the good of all consciousness to form my intentions throughout the session. The insight arose: any point within this experience can be an opening into the infinite space of open awareness. I found this was true, just as I had found it to be true in working with Reggie Ray’s embodied awareness practices, and with tai chi training. I reached a place of feeling at ease and stable, having in some sense crossed over. I could focus my awareness on the body, relaxing the legs and feet and face. I could welcome awareness, and allow it to deepen without limit or obstruction in any sense or any direction. Then arose the insight of suffering: beings everywhere imagining themselves to be separate and isolated, when in fact we are all participants in – and embodiments of – awareness. I turned back towards this suffering with a sense of profound grief, and also knowledge that my vows and my intention meant I could not shy away from it. Beings are numberless, I vow to free them all. Delusions are inexhaustible, I vow to let go of them all. Dharma gates are boundless, I vow to enter them all. The Buddha way is unattainable, I vow to embody it. I remembered two photographs of my father I had looked at the night before: 1. my father is in an airplane, sitting next to my little nephew, and looking really creepy: grey, puffy, fat, sweaty, hairy. next to him, the boy is sweet, perfect, shy. my father is trying to protect him, but his idea of this is plainly insane with worry and control. 2. my father is holding a bunch of orange dahlias, and beaming at the camera, at my mother, at my nephew. He is still in the body of a man who eats too much, and probably drinks too much, and works too much, but he is radiating pure joy. the picture is captioned in pencil, in my mother’s writing, Goompa’s pom-poms. Goompa is what my nephew calls his grandfather. I found myself entering the state of being my father: the heaviness of an unloved body, the way he tends not to see his inherent good qualities & is thus constantly laboring to justify his existence and stave off annihilation. I found myself entering into the being of my mother & brother in this way, and then my husband, and my dog. It was hard to go into the dog: the distance felt greater, and also the grief. On retreat three weeks ago, I studied the Vajra Songs of Longchempa, which include the bodhicitta that exchanges self and others. In the next phase of the session, I found myself doing this literally. Exchanging self and other: entering into the consciousness of others, now without the layer of grief I had felt so deeply, earlier. The insight arose: if I am in here, awakened awareness is in here, and so within any possible state of consciousness, awakened awareness is present. No one is alone. No one is cut off, whether they are conscious of the connection, or not. I found myself traveling back to a resort in Bali, where a group of followers of an enlightened Australian man were staying. I could see all of us there, at breakfast, eating fruit & honey & delicious red-rice bread. I could hear one of the disciples telling me about her teacher, how amazing he was, and I entered into that mind, where I saw there was a spark of awareness that knew this whole thing was a game: she was primordially just as awake as anyone, and while it was fun traveling to Bali to be with An Important Person, ultimately the task was to be in her own true nature. I visited some Klansmen at a rally in South Carolina: what are you up to? I could feel that part of the pain they were experiencing was the internal knowledge of falsehood, which needed to be staved off with ever greater displays of aggression. Throughout all of this, there was a sense of not clinging to anything, of allowing consciousness to travel. Sometimes I felt a sense of pause, of gathering. To what shall I apply this consciousness now? I found if I waited a bit, an answer would come. Either it would be time to shift into one of the meditation sessions, or some new imagery would arise from within the music, or elsewhere. I could feel it was important not to become attached to the stuff that was happening, and to check in with the space of awareness itself, resting there. I felt aware & immensely grateful to the lineage of teachers, known and unknown, who have kept the teachings of primordial, compassionate awareness alive and available in this world. The meditation sessions were welcome. All three – breath, metta, open awareness – were felt as expressions of the same seamless consciousness. At the same time, each one was like a stone thrown into a pond, causing different ripples. I was aware of being grateful for the opportunity to be a good citizen, and let go of whatever was happening, in order to focus on the room, and my guides, and the meditations. I was aware of taking pleasure in good citizenship, and in not indulging in focusing on the extraneous, exotic elements of my experience. True, one of my guides was giving off rainbows, and it was a little harder than usual to tie my pants, but, c’est la vie. The end of the session felt sweet. I could tell I was returning to something more like where I tend to spend my days, and the music came to feel like a lovely line back into the world. I felt like a kid in bed, listening to her Walkman, and enjoying the beauty of the sounds & lyrics. Ladysmith Black Mambazo singing Reveal Yourself struck me as especially moving and apt. I am immensely grateful for the opportunity to do this work in such a beautifully supportive and well-thought-out environment. May these insights and experiences be for the good of all. Something's cooking in that plastic bag from the co-op on the ground over there, next to the empty triangular sandwich box. We don't really want to know, and it smells bad enough that we are going to move to a different table. Poo? Garbage? Death? Something's always cooking, and if it weren't, there'd pretty soon be no room left for everyone. That's what the old lady in the deep-quarantine section of cancer-town said to me, that afternoon, pale wintry light filtering in through the window by her bed. She'd just been telling me about how much she loved her life, her daughter sitting by her side, her grandchildren, all the places and people she'd given her heart to over many decades. Oh, I'd love to keep living if I could, she said. And then, looking me straight in the eye, But if I could, so could we all, and then the world would get awfully crowded. She'd had her turn, and loved this life so much that she was willing to give it up, for its own good. We start off sort of sparkly, but underdone, and gradually mellow into the deep, funky flavors only possible through surrender, transformation, and decay. We Roquefort. We kimchi. We go deep. Our capacity to be delicious is infinite, though elective. There are beings who become more intensely flavorful as they live on, and others who soon dry up and get rubbery. Of course, we can choose to be re-born, re-basted at any time. It all comes down to: what do I think I am? If everything, then some seriously special sauces will make themselves available throughout life. If this little thing, then the juice runs out. That's about the shape of it. Yesterday, hungry after teaching , I wandered out into the sunny afternoon in search of something to tide me through grading and tai chi. I entered the dim, fancy confines of the underground place on the corner. Cakes, cookies & chocolate bits, all of which I steered myself away from & towards the quiches. Leek and goat cheese. OK. $7.10 later, with an extra $1 to the tip pot, for the lady with the winged rock-and-roll mudra on her chest (at least I never have to do THAT again, she says), I am sitting on the strangely low, broad red couches of the art building with my food. Expensive quiche: thick, bland butter crust, thick, bland creamy filling. It's not actually very good, tasting of small-business insurance, no-risk guarantees on handmade mattresses, and the boredom of institutional cooking, where no one's allowed to grab the pot of paprika with a mad gleam in her eye, saying THIS! THIS is what quiche tastes like today! Still, it's food, and it does a fine job of keeping me grounded through seven students' worth of projects, before heading to the river. I quit working in commercial kitchens when I realized I am completely uninterested in producing the same thing, reliably, time after time. I am interested in what THIS moment tastes like. I am interested in licking the spatula straight out of the food processor, to see what today's pesto is like, and gobbling it up while taking sips of glorious icy-sweet lime-slice gin and tonic. I'm interested in resurrecting the gamy and the dead - taking the world's flawed and leftover ingredients and combining them into forms of deliciousness that are irreproducibly born of this moment, with all past experience woven into now, but not dictating it. I am a disciple of the unbinding of the pantry cupboard and the refrigerator - how ingredients sourced, grown, given & bought suddenly come together in their own extinction and rebirth. Now-soup! Now-spread! Now-pie! I am drunk with making, I am reading the fullness of the world in this kitchen, abandoning what is not in favor of What Is. This body is made of such feasts. This body is a vehicle for feasting, a feasting-magnet, celebrating the plenitude of the ordinary. When I first started cooking in this way, I was living at Amaravati Buddhist Monastery, in the countryside outside of London. Some of the very basic ingredients the community had to cook with were purchased from supporters' cash donations, but everything else depended on a lottery of generosity. Unpacking the plastic bags left in front of the altar during big Sunday gatherings, it was possible to guess who the donors might be. A Thai lady working in a restaurant. Not much money. Bit of greens, white rice, soy sauce - what her grandmother might have put in the bowls of the monks walking barefoot through her village on alms round. A suburban middle-class family, into holistic health: sealed packet of organic baby corn, organic tinned chick peas, miso, organic broccoli, nettle tea. A family with small children: granola, white bread, chocolate candies, digestive biscuits. Out of this disparate array, each day a meal needed to be conjured for 60 people who ate breakfast (huge pots of tea & gruel) and lunch (whatever-miracle-buffet), but not dinner. Each day there was a Head Cook, who took advice from the kitchen manager, an eccentric Croatian monk who eventually disrobed, went back to being Zoran, and struck up a relationship with a formerly fearsome-seeming lay member of the community. Zoran liked to wear a purple velvet tea cozy on his head as a sort of papal toque. His authority, thus affirmed, was important in reining in the devotional zeal of certain Head Cooks who otherwise would have appropriated all the best ingredients for their own efforts. I learned to like cooking with the stuff nobody wanted to mess with, because it was weird, or there was hardly any of it, or it was bad for you, or whatever. This practice of taking manky bits and cooking them up into something sustaining and good is interrelated with the Bodhisattva Vows: beings are numberless, I vow to free them all; delusions are inexhaustible, I vow to let go of them all; Dharma gates are boundless, I vow to enter them all; the Buddha way is unattainable, I vow to embody it. Ramen stew and twinkie pie, I vow to free you all. Fears of poisoning, allergy, fattening, and skinnying, I vow to let go of you all. Impossible arrays of mismatched foodstuffs, I vow to enter you all. Perfect meal of unbounded generosity, I vow to give you form.

One winter at a sister monastery, I did get really skinny. I was on three-month monastic retreat, and the two sweet young men in the kitchen were consistently not preparing enough food so that I, at the end of the line, could have anywhere near the amount I usually ate, and leave anything for them. So I shrank, to the point that the window in my sternum became visible, and my ribs stuck out. This was good practice: here is what hunger is like. I've thought all kinds of things about food, and I've gotten sick all kinds of times: from plague-bearing clams in Tsim Sha Tsui, and from Delhi's awful sludge, clinging to the delicate skins of the cucumbers I couldn't not-eat on a sweltering day. In all of this, something's cooking. The Buddha died of someone's cooking, to make room in the world, to allow himself and all of us the liberation of an ending. So it goes, and so it will go, world without end, Amen. Lately, Chloe's taken up air-humping our house-guests. It's something new and fresh for all of us, growing out of the trauma of her surgery and having to wear the Very Large Array for weeks. Also, less dramatically, it's part of the basic condition of being a house-dog. Chloe's air-humping John and Sunny, and Iseec and Leah, is a way of testing the waters. Who am I, here? How will these people respond to a little test of Chloe Is the Queen Around Here? And the wonderful thing is, we are all doing this all the time. Women who walk into a room and reflexively scan all the other women's clothes and hair to see who's got what going on. Men who scan a room reflexively for fuckable options. Travel-stories and kid-accomplishment-stories; stories of this Tibetan lama, or that. All of it is total air-humping. Will they notice me? Will they hear the name of So-and-So Rimpoche in association with mine, and forego the sharp teeth they would otherwise fasten around my neck? That would be so nice. So nice not to have the fangs, the blood, the humiliation of being on the ground again, pinned under immovable weight again. My kid is learning to sail in France. I got promoted to deputy manager for international operations. Please don't cut me open. Students do this. I'll explain an assignment what seems like straightforwardly, and then there's always someone who wants to air-hump their way out of it. This dynamic is very different from those who just hear the assignment, let it process through their awareness, and go do whatever they're going to do with it. Those ones don't have any time for air-humping, because they're too busy making art. They vanish, go find what needs to find them, and come back radiant with discovery and self-confidence. Meanwhile, the air-humpers - and this is pretty well all of us, at one point or another, a transpersonal force - want to be affirmed in their transgression. We can't face going to dwell in the unseen. We need assertion-with, or assertion-against. My teacher says. My party says. My great-great-great grandfather, Nathaniel Bedford Forrest says. On and on. Chloe, living with a gimpy leg, outside her species. I get it: confusing. Rules not her own. Get used to these two goofy humans, and then here they come, bringing new ones into the house, with bottles of wine, foot-cream, and Zionist flags. Now what? Yesterday, I read this: That the self advances and confirms the ten thousand things No self to confirm: awakening. Embattled self always seeking affirmation: endless air-humping, plus fangs. So it goes.

Chloe, Chloe. Such a happy animal sometimes: prancing on her wolverine-feet, smiling her little lower-teeth smile as I pull together poo-bag, hat, leash, shoes. She doesn't need any of that. She's ready in her suit and shoes anytime. Her ears ready to hear, eyes ready to see, paws ready for the ground in all its forms. Three paws firmly grounded, one more tentative. Chloe poops brazenly on Jack's immaculate lawn, seeing only: this green world. She eats blades of long, fresh grass, savoring the summer through her curling pink-black tongue, bringing the world into herself, herself into herself. There is so much air-humping in religion: lovely, simple gestures that have hardened and lost the freshness of discovery. Everyone apparently knows to bring a white silk scarf along when it's blessing time with a visiting lama. We bow, we put our scarf around the holy one's neck, the holy one puts it back around our neck, we bow again, and pack up for the next time. Hum de dum. The gift and return are beautiful in intent, but what about all of us instead tying our scarves end-to-end, and playing twister? Or mummifying ourselves in blessings? Wrapping Tara in silk until she is a tufted titmouse, with golden toes and bun protruding. There are more possibilities than we know & it is good to go into the dark and find them. Air-humping the house-guests. Everyone's met a bad dog and the people who enable her. My grandparents used to blame my brother and I when Fanny the cocker spaniel would jump up and bite us on the ass. Fanny had no time for air-humping - it was straight to the fangs for her, and no hesitation. Something about my grandparents' régime brought this out in dogs - Tessan was a toe-biter, and poor Bendy was put down after mauling my grandfather once too many times. He was a golden boy, all blond feathers, and not nearly enough no. We don't give house-dogs room to go into the dark and figure themselves out. Farm dogs are different. They have a world to roam in, and a job to do. They will show fangs when needed, and as for air-humping, why bother with that, when the real thing is on offer, with that feral coyote in the windbreak? The vet thinks part of why Chloe's knee is damaged in the first place is that she was spayed too early, and so her muscles & tendons & bones & ligaments didn't get the hormones they needed to knit up strong. Poor beasties: we are so concerned with securing their well-being that we stunt it from the beginning. No time for the dark: the force of reason requires the light, the rational solution. No time for Moonbear pups for the Moonbear to lick & suckle & protect. We have gone a long way together. We are good at making ourselves lonelier. We do the best we can with what arises, and try, again, again, to tune to the mind of discovery, of neither for nor against. We put the dog in the crate in the dark for awhile, and then pay close attention to what emerges, smiling with little lower teeth, and eating marrowfat in the corner of the kitchen. We meet here, under these trees, to look into what is, to know this, and that, and to choose wisely. We let our loins rest from air-humping the world, and we relax. Because Erica’s getting older, there’s a lot less to worry about, on the cosmetic front. I mean, when you’re 17, it makes some kind of sense to buy & even to apply teal eyeliner, magenta lipstick, foundation goo intended to laminate your zits into hiding, but let’s face it, as Erica and I are getting older, we don’t give a rat’s ass. Sometimes it still happens that I see someone with perfectly applied swooping black wings on her eyelids, and I think, what a glorious thing! But then, in CVS, with my 2-for-1 deodorants and fluoride rinse in hand, I just can’t find the self-seriousness or the stamina to face the endless wall of goony-eyed models, select a vial of product, slide it out of its glamor-silo, and pay $17 for it. It just doesn’t happen, because I’m getting older, and so later, when it rains, I don’t have to worry about blotchy, itchy flakes of black in my eyes. I can cry with abandon, and not feel I am ruining anything. I can fall asleep anywhere, wake up, rub my face, and everything’s fine. I used to be a real zealot about my black lines. On the long flight to Tokyo, when I was 21 and wing-eyed, the flight attendant asked me whether I was part-Japanese, because her child was going to be, and she was hoping her daughter would look like me. A guileless and flattering thing to say, though only really possible from the perspective of looking down at my 6-foot body. I told her I knew her children were going to be beautiful. I carried my Revlon liquid liner all around Shikoku Island, walking with a backpack full of film & books & only partially effective rain gear. I could not imagine letting the world see me without a decorative awning, even though the world was mostly temples, rice fields, and the old people who had bent in them for centuries. They didn’t care. I cared. I slowly learned not to in the subsequent years’ travels. I learned to see my face naked and accept it that way, and not need to put black lines between my gaze and others’. Then for a while I wore enormous British National Health Service glasses with thick lenses that created their own kind of distance. Because Erica and I are getting older, I am pretty sure that 4th of July anxiety doesn’t apply as much anymore. I mean – I’ve known all kinds. Most of the first 16 or so were spent in France, where the 14th was the real deal, and the only people paying any attention to the 4th were the American sailors on board the destroyer they would park in the Baie de St. Tropez like a great gawky stretched-out Escalade puffing its uncool chest outside a club everyone else walks to. My uncle, unwisely, pointed his little grey rubber Bombard at it, full-speed, gesturing and yelling Poussez-vous! A stunt best done before The War on Terror, in the bare-breasted 1970’s, to be sure. So the 4th of July is historically not my thing, except for one spent in San Diego with some friends of my parents. We went to picnic by the harbor, and stayed for the Pops, followed by tremendous fireworks: a whole American flag at ground level, with larger explosions above, and parts of the great American fleet looking somehow flat-grey and festive at the same time.

When I came back to the US from the monastery, suddenly the holiday arose with a whole new urgency, showing me I knew no one to spend it with – at least: no one whose family space would include me. I felt a sharp pain at being left out of what claims itself as everyone’s holiday. Not everyone’s. I was deportable. It was not clear where I could be. No country for bald women. Ashamed of loneliness, I felt it more keenly. But now I know. Sit still long enough on the porch, reading out loud to myself, and sipping on a gin and tonic with cucumber slices, and a hummingbird will come to hover snoutily at the delphiniums, and dart away to its home, far away over the sumac. The feeling of one-ness, now-ness, sacredness, and participation will seep up from the ground, and drift down from the sky. It will open from the heart of its own accord, 4th of July or no 4th of July. There may be pie, or not. Sacred space is here. Here under the wide shade of the river-fork trees, here where crazed chipmunks dart up the linden trunk, in the lee of the parking lot, in the lull of the traffic, in the shelter and company of all beings who take refuge without begrudging the moment anything. Because Erica and I are getting older, because I am getting older, I am better at filtering out and filtering in, though it’s still hard for me to say no when obligation arises. No, I will not bend myself into crazy shapes to meet a need that comes up like a rumor of war from another country. No, your perception of emergency does not necessarily involve me. The trees smell good here. I have my own work to do. May yours go well. I think it’s very important to know that we meet at very particular points in vast rolling cycles. Ask me one morning, coming from your own spaciousness into mine, and there will be effortless, obvious yes. Ask me two hours later, after the locked doors and obstacles of a new batch of emails, and I won’t be able to find a truthful yes for you. If I’m careful, I won’t lie one up for the sake of decorum. I won’t paint the black lines on, and you’ll be left to decide whether to drop it, do it yourself, or ask someone else. Truthfulness is changing because I’m getting older. Not the young woman’s crusade anymore. More like the older woman’s considered evaluation of what’s happening in nearby territory, and in the inner hinterland. What can be said and heard? What can be said and not-heard, but needs to be said anyway, because it’s cowardly or condescending to hold it back? What deeply uncomfortable truth needs out, so that the illusion of an infinitely competent and energetic self gets laid to rest again and again? Because I am getting older, I know exactly how much I relish bed at 10PM, the fat science fiction novel and the succor of pillows. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed